This is the second part of a 2-part essay on “Aesthetic Chills.” Part 1 is here.

In the first part of this essay, I looked at what the conditions are for “aesthetic chills” in general. But since this is an art publication, the major question is going to be: When might the kind of art you find in a museum or gallery elicit a chill, specifically?

In my informal survey of colleagues, art writer Julia Halperin was one of the very few to reply straight off with a clear-cut art example: Janet Cardiff and George Bures-Miller’s installation Forty Part Motet (2001). This is a little bit of a cheat, since that is a sound art piece, 40 standing speakers arranged in a circle playing a medieval choral arrangement by Thomas Tallis (1505-1585). The otherworldly harmonies of Tallis might well be chill-inducing on their own, in or out of the museum.

Julia did say that the exact moment that the chill hit was when her brain clocked the installation’s central device: that each of the speakers isolates a single voice from the choir. So, there is the classic collision of different moments of revelation, as I described earlier.

What does it mean that “museum art” doesn’t tend to be people’s go-to example for chills? Art that provokes an “aesthetic chill” is emphatically not a synonym for “good” or “bad.” But the relative absence does tell us something about the specific kind of thing visual art is.

Why Art Has No Chill

In Part 1, I came to a personal formula for the conditions for an “aesthetic chills” experience: “a rush of emotion, presented in a novel way, connected with intense personal feeling, and found in an unexpected place.” If these are the features of the terrain, you can see how visual art fights at a disadvantage in each. Let’s look at them one at a time.

“A rush of emotion”: The “aesthetic chills” effect seems very tied to time-based media. To have the experience of revelation or of a burst of new feeling that typically triggers a chill, it helps to be working in a medium where patterns are built up, so that they can be broken in an exciting way. And this is just easier to do in songs or stories, and harder with single images or objects.

“Connected with intense personal feeling”: Art’s ideal of prestige still associates emotional restraint with high status. More subtly, not all types of feeling are equally conducive to chills. In particular, the experiences that museums are best adapted to—contemplation, contentment, delight—tend not to be associated with the quick movement between different emotional states associated with chills, because they are equilibrate.

“Presented in a novel way”: Contemporary art has considerably diversified in form, and now does feature time-based media, from video to performance to sound art like Forty Part Motet. However, that very diversity may well mean it suffers from too much novelty, not too little. It is no surprise if an artist shifts styles radically between or even within works. There is much that is positive in this freedom—but you can’t have the experience of rupture that triggers a chill if there are no rules in the first place.

“Found in an unexpected place”: Wall labels often fundamentally serve as spoilers, telling you the right thing to think, so you never have the experience of being productively unmoored (part of why people are so fixated on spoiler warnings in film or TV is because you might have a potential chill ruined). It is possible to have an unexpected experience in a museum—in fact, I often say that the best museum method is to wander, find one thing that unexpectedly seizes you, and just stay with that feeling. But in practice, the art experience is often more about “demonstrating your ability to recognize things already understood to be important” than having a personal and unexpected encounter with those same things.

Museum technicians prepare wall labels at the Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza on October 11, 2016 in Madrid, Spain. (Photo by Pablo Blazquez Dominguez/Getty Images)

Having laid out the negative conditions, maybe we can focus on what kinds of encounters within a museum or gallery might make an “art chill” possible.

One thing I’ve realized as I have looked into the subject is how personal the experience is, how based it is on finicky, hard-to-replicate circumstance. So I will speak personally.

I can remember exactly three times it happened for me—just three.

2010

That year’s Gwangju Biennial, called “10,000 Lives” and curated by Massimiliano Gioni, was one of the most successful big art shows I’ve seen, full of spooky, unexpected art and lovely juxtapositions. Gioni has a knack for bringing out unexpected sides of familiar figures, and finding new emotional through-lines. That background climate is important: In my experience, an “aesthetic chill” is helped a lot by mood and atmosphere that sets it up, sort of like how the steady raising of temperature by degrees prepares the way for the moment when a pot boils over.

The exact moment in “10,000 Lives” that gave me a physical chill did not relate to a big name artist or something I knew—it was unexpected. It was a work of what you call “vernacular photography,” a display of 62 images depicting a man named Ye Jinglu, who had photographed himself in a studio in formal garb every year from 1901 to 1968, from when he was 21 to when he was 88, the age at which he died. The works were found in the trash and saved and have since taken on a life of their own as an aesthetic artifact.

A photo from a 62-year photo biography of Ye Jinglu, discovered by Tong Bingxue. Courtesy Tong Bingxue.

The photos themselves are simple, relatable if you’ve ever taken a graduation picture. You really feel like you are watching one man age, from a young person full of swagger to someone whose eyes are more guarded, who has seen a whole world change around him. I remember walking slowly past the photos and having a thought suddenly enter my head: “At the end of this wall, this guy is going to be dead.” Which is when a shiver went down my spine.

I can confess this was a turbulent time in my life. A fiancée had just left me. I was thrown off my center and thinking about changing my life.

Today, if I say out loud that the Ye Jinglu photographs suggest to me “putting on a brave face as life’s disappointments wear you down,” it seems embarrassingly obvious why they would strike me, at that moment, on a gut level. But the connection between my own drama and the vivid thought that so moved me then, in Gwangju, was hazy at the time—I don’t think I actually made it consciously until I finally just put it into words now.

2015

Capturing a biography in freeze frames, the Ye Jinglu photos might be said to function as a film strip, which is important since a chill often appears where your emotional relationship to what you are perceiving changes in time. My second example is a single image—in fact, about as singular an image as there is.

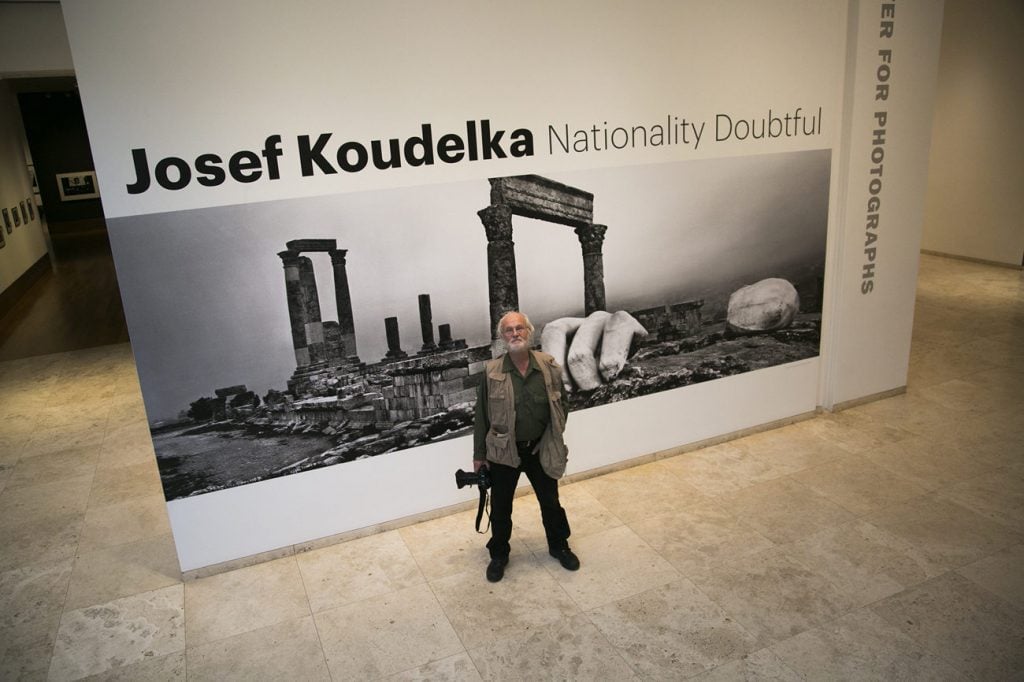

This is the most famous picture by Czech photojournalist Josef Koudelka (b. 1938). I say famous—but I guess it’s important that I had seen it but not thought much about it when I first came upon it a decade ago at the Getty Center in “Josef Koudelka: Nationality Doubtful.”

Josef Koudelka in the Getty Center galleries, November 2014. Image courtesy J. Paul Getty Center.

It comes from his coverage of the Soviet invasion of Prague in 1968. An arm juts into the frame from the left (it reads as the photographer’s own, though if you think about it, it can’t be—it’s a man he grabbed to pose for it). The wristwatch is framed at the bottom as Koudelka shoots over it into the street below.

It’s an odd but ingenious gesture, and there aren’t many other photos exactly like it. I had always thought of it as being “about” how dead time takes on a different, sharp-edged meaning when something big is about to happen—in this case, an invasion.

This is a common misreading of the photo, which actually takes place after the invasion, and depicts Wenceslas Square, where a demonstration was planned at that exact time. In Koudelka’s account, he meant to take a picture of the Soviet tanks alone in the square, and what the photo actually shows is the discipline of the population, seeing the gathering as a trap.

A visitor walks by the ‘invasion’ pictures by Josef Koudelka during the presentation of his retrospective exhibition in the Athens Benaki museum on September 16, 2008. (Photo by Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP via Getty Images)

At the Getty, looking at the crisp black-and-white details up close, I realized the photo was not of something about to happen, but of something that was happening that I hadn’t seen. Mentally, the effect was like a lens suddenly racking focus from an object in the distance to something up close.

Amorphous memories came tumbling into the historical scene of moments on the street, late at night—the kind of moments where being alone goes from feeling like you have nothing to worry about to feeling like something is off, that there must be some reason that no one is around, and to feeling vulnerable. The empty square went from suggesting an absence to a presence—the presence of dread. The photo went from an intellectual experience to one I felt. And at that moment it zapped me.

2023

The final chills moment was recent. I’ve talked several times in the last year about how much I appreciate the work of Colombian sculptor Delcy Morelos, and specifically her recent show at the Dia Art Foundation in New York. These two room-filling installations of abstract earthen forms had, for me, everything—they were familiar but novel, visceral yet brainy. Morelos specifically uses smell as one of the elements of her installations—her materials have a clove-y, cacao scent—so my brain was buzzing with more than it was used to in the museum.

Delcy Morelos, Cielo terrenal (Earthly Heaven), 2023, at Dia Chelsea, New York (detail). Photo by Don Stahl, ©Delcy Morelos.

My “chills” moment at Dia was specific to me, as it was very much based on not knowing what was coming. It came between the first and second galleries. I had spent 20 minutes or so absorbed in the first large installation called Earthly Heaven, thinking wrongly that it was the whole show: a low-lit landscape of intricate abstract forms laid out on the ground, running off into the deliberately darkened space so that you have a feeling that it goes on forever. I was immersed in its atmosphere, and admiring how it was playing with my perception, making me feel as if I were a giant towering above an alien landscape.

I noticed other visitors exiting to the neighboring chamber. Following them, I found myself abruptly in the presence of the second part of Morelos’s show, The Embrace—an immense sculpture of earth that towered to the ceiling and filled that room, pushing me back against the wall.

The shiver of electricity that I felt then overlapped with the admiring epiphany that the carefully controlled mood created by the previous room had been setting me up for this experience of reversal, being made to feel big so that I could be made to feel small—very much an end-of-The Sixth Sense experience of revisiting a story you just been through and, in a flash, reinterpreting what it had been showing you.

Delcy Morelos, El abrazo (The Embrace), 2023, at Dia Chelsea, New York (detail). Photo by Don Stahl, ©Delcy Morelos.

I went to see Morelos’s show at the end of 2023 on a gloomy afternoon, and I think I had also been feeling a little depressed about the state of art, and by extension the state of writing about art. I was feeling thinned out. I had been thinking about how disembodied and fleeting my experiences of art and writing felt. And in that moment of unguarded awe at Dia, the change of scales felt like a change of moods too, as I literally went from looking at the ground to looking up.

It felt like sun breaking through the clouds.

Shocks of the New

The above are all powerful memories of art for me, but they hardly exhaust my powerful memories of art. We’re talking about just one effect that art can have, in some specific circumstances (in fact, the research says that not everyone even experiences chills).

Nevertheless, pondering the phenomenon has been humbling to me, in a useful way. Every part of this essay has been a little embarrassing to write. In Part 1, because the chills-inducing materials were not what a serious audience for art would call “good” (the movie trailer, the YouTube montage). In this part, because thinking through my own experience makes me fess up to points of ignorance against which a moment of realization appeared, or disclose some connection that was personal, very specific to a time and a place for me—basically, stuff that I’d naturally smooth over if I was trying to explain an artwork to a broader audience.

And that’s interesting! I’ve come to think that “aesthetic chills” open a window onto the fact that there are decisively powerful areas of art experience that are only explained by admitting to stuff that you tend to suppress in order to make that experience respectable.

In a lot of the research I’ve read, receptivity to “aesthetic chills” is associated with openness to new experiences. Chills are certainly pleasant and people seek them out—but they are also connected with feelings on the turbulent or troubling end of the spectrum. Almost as if they are a location finder pointing you towards experiences that are transformative, but outside your comfort zone.

It’s a truism that most of what will later be seen as vital in art appears at first as off, unpleasant, or out of place. So perhaps there is something in this subject that is not so niche or trivial, after all. Perhaps thinking about this particular experience might in some small way help us be open to the energies that move things forward.

***

Very likely, others have experiences of “aesthetic chills” that are totally different than mine. I’m here to hear it! If enough people tag me with their most memorable examples from an art context, I’ll publish another piece gathering them or shouting them out.

You can find me on Bluesky or Instagram (my preferred services these days). Or just write me an email at bdavis[at]artnet.com.