In 1993, completely out of the blue, the Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda was sent a photocopy of a manuscript purporting to be six lost Haydn keyboard sonatas. It came with a letter from a little-known flautist from Münster, Germany called Winfried Michel, who told Badura-Skoda that he’d been given it by an elderly lady whose identity he could not reveal.

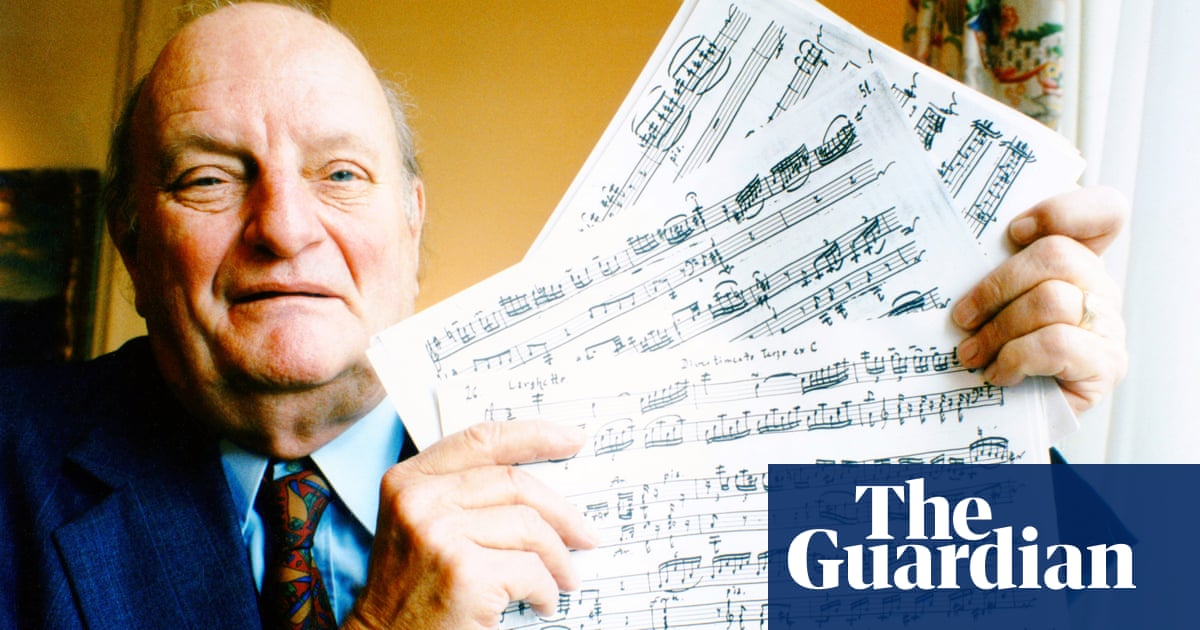

Badura-Skoda was suspicious, but once he played the music, he became sure that the works were real. He asked his wife Eva, a musicologist, to examine the manuscript. Although the music wasn’t in Haydn’s hand, she believed it to be an authentic copyist’s score dating from around 1805 and originating in Italy. They checked with the Haydn scholar, HC Robbins Landon, and he too was convinced. He penned an article for BBC Music Magazine, headlined Haydn Scoop of the Century, tipped off the Times, and called a press conference for 14 December 1993.

Within hours, the Joseph Haydn Institute in Cologne declared the manuscript to be a fake. An expert from Sotheby’s in London agreed. The Badura-Skodas had been hoaxed, or so it seemed. The following February, Eva gave a talk in California titled: The Haydn Sonatas: A Clever Forgery. Paul played a selection of the works – in a confused state of mind. Eva told the music scholar Michael Beckerman, reporting for the New York Times, “My husband still thinks they’re genuine,” raising difficult questions about truth and art. What did Paul believe he was playing? What was the audience hearing? And did it matter?

In his article, Beckerman wrote: “Knowing that a work is by Haydn or Mozart allows us to see ‘inevitable’ connections. Take away the certainty of authorship, and it’s devilishly difficult to read the musical images within.” He noted, too, that it was the inauthenticity of the manuscript that had exposed Michel and not the fidelity of the music. And so, Beckerman dared to ask: “If someone can write pieces that can be mistaken for Haydn, what is so special about Haydn?”

Does Beckerman think there’s much to draw from the story of the lost Haydn sonatas if we consider it today? “I think it pushes us to question what it is that we know,” he says. “How do we come to know it? And then how do we express it to others? And, in particular, how do we express it to others who might not agree with us? I think those questions are still completely apropos, and this kind of forgery pushes us to keep asking those questions and not pretend to know stuff that we really don’t know.”

What makes something a fact? In the catalogue of their works, the Milan-based music publisher Ricordi lists the well-known Adagio in G Minor – a staple of film scores, including Gallipoli, Rollerball and Manchester by the Sea – as being by the Italian baroque composer Tomaso Albinoni, but elaborated upon by a musicologist called Remo Giazotto. Giazotto claimed that he completed the work in the late 1940s from a fragment of Albinoni’s actual music – a bassline and two short melody parts. But as the Albinoni expert Michael Talbot tells me: “Giazotto never provided any satisfactory explanation or description of the source from which he took the fragment. My view is that it’s an original composition.”

Ricordi first published the work in 1958. I asked why they continue to list it as being at least partially composed by Albinoni when the connection can’t be proved and they didn’t respond. But the problem for any sleuth that examines the case of Adagio in G Minor is that its connection with Albinoni can’t be comprehensively disproved. Unlike with the Haydn sonatas, there is no original manuscript for specialists to discredit, only evidence collected by the likes of Talbot pointing to the likelihood that it never existed.

Giazotto, who died in 1998, never owned up to his suspected hoax. After his manuscript was rubbished, Winfried Michel called the Haydn sonatas “completions”, without explaining what he meant. It would take until 2022, three years after Paul Badura-Skoda died, for him finally to disclose to a newspaper in Münster that he had composed the works, inspired by the incipits – their genuine opening four bars, which had survived in a catalogue of Haydn’s works. There was a bed of truth on which to sow the seeds of a very tall tale, as there was in the strange case of Joyce Hatto, the English pianist who enjoyed a late-life detonation of success in the early 2000s. Her husband, a record producer called William Barrington-Coupe, palmed off more than 100 CDs of other pianist’s performances as her own while she was ill with cancer, fooling critics. If Hatto hadn’t had an actual career between the 1950s and 1970s, the hoax would never have been believable. She died in 2006, a year before the ruse was uncovered, resulting in many Hatto obituaries remaining online – including on this website – that are a discombobulating mix of truth and nonsense.

Musical hoaxes force us to question not just authenticity and ways of knowing, but also how we define words. In 2014, the supposedly deaf composer Mamoru Samuragochi stunned Japan when he confessed to using a ghostwriter for the 18 years in which he’d become famous for writing video-game scores and traditional classical music, including a symphony dedicated to the victims of the bombing of Hiroshima, his home city. He also wasn’t legally deaf. The ghostwriter, Takashi Niigaki, worked to Samuragochi’s briefs. How do we define a composer in that equation? And who was the artist? The story is rich with irony; after the hoax was exposed, Samuragochi became a recluse, Niigaki a public figure. “It was like Samuragochi had the temperament of an artist, but lacked the tools to actually create art,” wrote Christopher Beam in The New Republic. “The closest he came to a masterpiece was the performance itself: the mass duping of a nation that exposed its own dreams and vulnerabilities.”

In a 2013 book, Forged: Why Fakes are the Great Art of Our Age, Jonathon Keats wrote, “Art forgery provokes anxiety.” He was referring to fine-art, but perhaps his views apply here. “Because art is a rare refuge from the mass-produced inauthenticity of the industrialised world, we are hypersensitive to any threat to the authenticity of art.” As such, he added, “No authentic modern masterpiece is as provocative as a great forgery. Forgers are the foremost artists of our age.”

Let them also act as admonishers. A forger makes mincemeat of established narratives and gnaws at the rootstock of belief systems that shouldn’t be taken for granted. There’s art in the con, but also a warning.