Artists, museums and churches in Valencia, on the central eastern coast of Spain, face devastation following the deadly flash floods on 29 October that killed more than 200 people and caused widespread damage. Although the city of Valencia itself was largely spared, towns immediately to its south—in an area known as La Huerta or “the garden”—were inundated. Heritage sites were badly affected, some irreparably. The area is popular with Valencian artists, many of whom have lost their life’s work along with their workshops.

The artist Juan Olivares’s studio was already under a foot of water when he was alerted that the nearby ravine had overflowed. Twenty-five years of his work was stored on the ground floor of his home in Catarroja, one of the towns hardest hit by the floods. “I tried to save as many paintings as possible by moving them upstairs until the water reached my chest,” he tells The Art Newspaper. Olivares, who is internationally exhibited, returned to his studio the next day to find destroyed works, ruined tools and 20cm of mud. The basement stored a collection of his own pieces, two for every series he has produced throughout his career. “I haven’t checked yet, but I don’t think anything else can be saved,” he says.

Juan Olivares saved as many paintings as possible from his Catarroja studio until the flood water reached his chest Courtesy Alexandra Coego

Olivares counts himself fortunate; the floods in Catarroja were deadly and the house across the street collapsed. The town’s cultural spaces were also severely impacted, including the Antonia Mir Museum and the House of Culture. Catarroja’s city council has since confirmed that the damage is so extensive that a reopening of the two institutions in 2025 is unlikely.

In response to the humanitarian emergency, the artist Felipe Pantone launched Auction for Action, a fundraising effort to support Valencia’s recovery. Pantone, whose studio was also badly damaged, organised an auction featuring donated works from international and Valencian artists. Alvaro Góngora, the content director for Pantone’s studio, underscores the unity in the artists’ response: “Solidarity has been generalised to all sectors and neighbours, and in the art world it has been no less.” All proceeds will go directly to local foundations, with none allocated for personal restoration, even for Pantone’s own studio.

The speed with which the flooding took hold meant that many works could not be moved to safety in time © David Aparicio Fita/ZUMA Press Wire

“Having a workshop in La Huerta is something we Valencian artists dream of,” says Ruben Tortosa, a visual artist and fine arts professor at the Polytechnic University of Valencia. The floods destroyed his workshop near Xirivella, damaging works he had been creating since 1985. Tortosa explains that La Huerta offers affordable studios close to the city; for decades, artists have been drawn to its traditional agricultural buildings, known as alquerías. This has created a unique landscape of contemporary art co-existing with local heritage. “The culture is here, in these towns. It’s a fascinating heritage,” he says. Both Tortosa and Olivares recognise a loss that goes beyond the physical works—the unrealised potential of the art that will never emerge from the ruined studios. “Many things will be lost in silence,” Olivares says.

The Torrent workshop of the photographer Ricardo Cases was destroyed © María Mira

The floods were triggered by an intense weather pattern that brought torrential rain and caused rapid overflows of the Turia river and the Poyo ravine to the south of Valencia. While this area has historically been affected by flash floods, analyses from ClimaMeter and World Weather Attribution, published in the week following the disaster, indicate that climate change contributed to the extreme weather.

Archives and icons damaged

Although the full extent of the destruction is still unknown, users on X reported the collapse of the Jalance Bridge, a historical feature of the town of Requena since the 1500s, and that of the medieval aqueduct Els Arcs de Baix, in Torrent, where the workshop of the leading photographer Ricardo Cases was wrecked by the floods. The Archbishopric of Valencia also confirmed that the parishes in the affected areas suffered damage to their archives and, in some cases, to their icons. The regional department of culture is also evaluating damage to its collection of contemporary art and part of the collection of the Art Modern Institute Museum of Valencia, both stored in a reserve in the affected area.

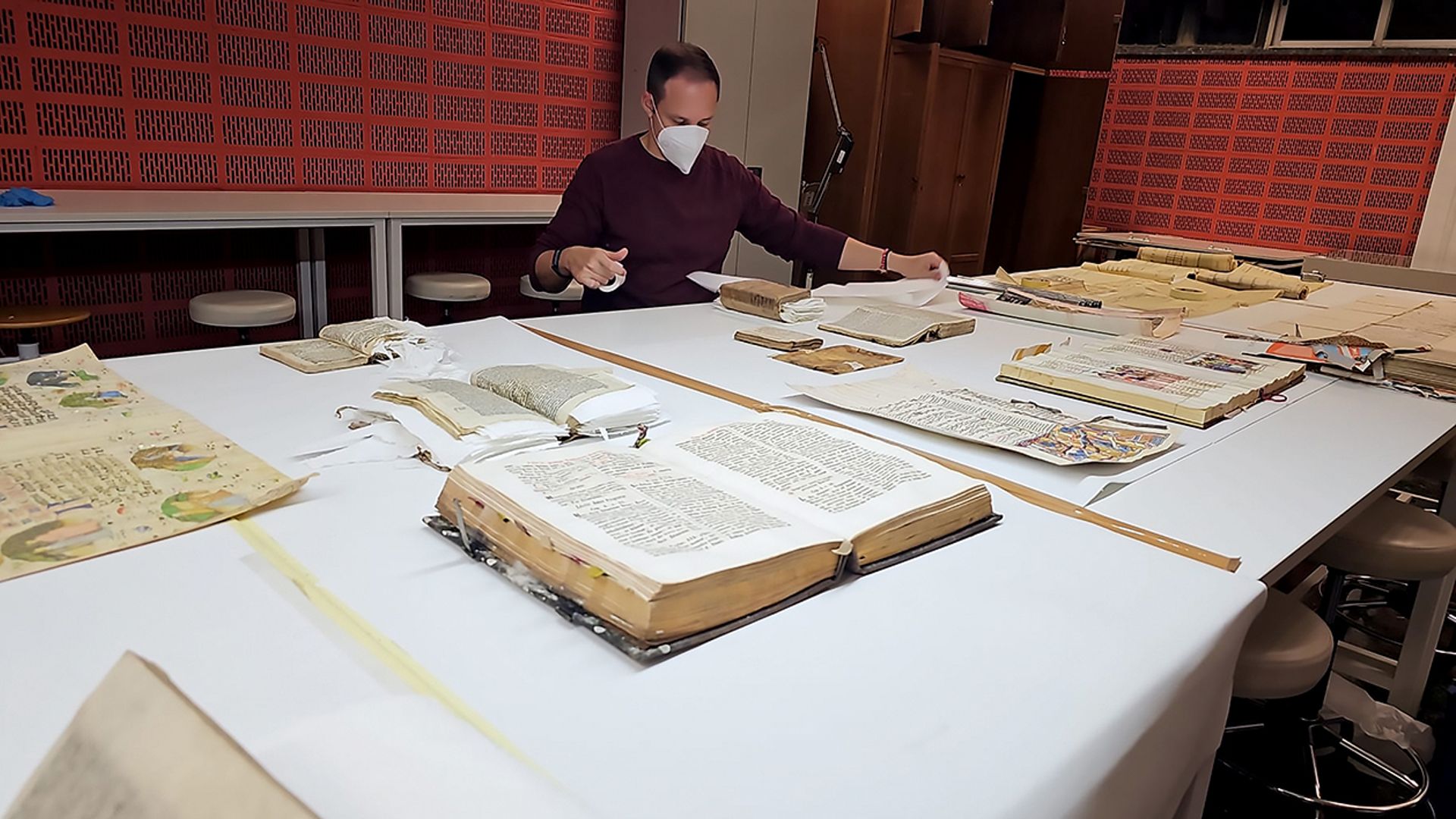

Works from Algemesí’s historical archive (right) are being dried in the University of Valencia, along with works of art from a retrospective on Messa, which had been on show in the town’s Centre of Contemporary Art L’Esart Courtesy Alexandra Coego

In the town of Algemesí, Alex Villar, the manager of the Centre of Contemporary Art L’Esart, has been co-ordinating clean-up efforts of its cultural spaces. The water rose to 170cm inside the centre, submerging parts of a retrospective of the vanguard artist Messa (1915-96) from nearby Albaida. “The works have all been enormously affected; they are panel paintings, some very delicate,” Villar says. Ukrainian contemporary art pieces that had been part of an exhibition in solidarity with Ukraine are among those affected. Four days after the flood, mud remained knee deep. After a first clean-up with the help of the city council and volunteers, “part of the historical archive of Algemesí and our artworks are drying in the University of Valencia”, Villar reports.

Other cultural sites in nearby towns have also suffered devastating losses. The Fan Museum in Aldaia, the only institution in Spain dedicated to this cultural object, sustained irreversible damage to part of its collection. In Paiporta, nine days after the disaster, staff were still unable to enter the Rajoleria Museum, fearing significant harm to the permanent collection.

Cars were swept away and piled up in Alfafar, a scene that was repeated across the region Photo: Angel Garcia; Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo

On 7 November, Ernest Urtasun, the minister of culture, announced the Plan for the Reconstruction of Valencian Culture, with a package of measures to alleviate the effect of the flood on the sector, mostly focusing on the cinema and book industries. For “cultural heritage and fine arts”, the ministry is assembling a group of technical specialists, notably architects and restorers, who may be mobilised at the request of the regional government. Pilar Tébar, the regional secretary for culture, met earlier that week with representatives of more than 60 institutions, associations and representatives from the sector to evaluate the magnitude of the damage. Villar rejects “toxic” rumours of a lack of support from the regional department of culture. “We heritage workers had their support from the first minute. They acted as soon as trucks could reach the museums,” he says.

Government under scrutiny

In Spain, regional governments are responsible for disaster management, including heritage protection. The co-operation between the central government and Valencia’s to respond to the catastrophe has come under heavy scrutiny, with accusations of negligence on both sides. A protest against the management of the tragedy was held nationwide on 9 November. The outpouring of grief and anger was targeted at the Valencian government, particularly its president Carlos Mazón, who had angered and frustrated many in Spain over his handling of the catastrophic flooding. In Valencia itself more than 130,000 protesters with hand-drawn signs, brooms and whistles filled the city hall plaza chanting “Mazón, dimissió” (Mazón, resign) on Saturday afternoon.

Inadequate insurance

While artists struggle to recover, many face an added obstacle: inadequate insurance and social protections. According to Alberto González Pulido, a legal adviser to the art market, few artists can afford insurance in these cases. “Insurers often offer specific coverage for natural disasters, including floods, but at higher premiums and under additional security conditions, such as storage in elevated or special areas,” he explains.

In the cases I am handling, nothing has been saved. It’s a dreadful situation

Alberto González Pulido, legal adviser

Some of González Pulido’s clients, including private collectors and artists who stored their collections and works in industrial warehouses within the affected area, suffered significant losses. “In the cases I am handling, nothing has been saved. It’s a dreadful situation,” he adds. He also points out that future aid programmes for artists may only benefit those registered as self-employed. “That is not the case for the majority of them. Registration is a root problem,” he says. In Spain, registration fees for artists are a minimum of €161 per month, even when income is zero. While the Spanish prime minister Pedro Sánchez’s government introduced a Status of the Artist in 2023 to improve social protections, visual artists were notably excluded from the reform.