CNN

—

It may be an archaeologist’s job to unearth astounding discoveries, but every year some people just have an extraordinarily lucky — or strange — day. That was no different in 2024, with a construction worker turning up a nude marble deity hidden some 1,600 years ago, an art historian spotting a missing painting on his social media feed, and an amateur excavator digging up a confounding ancient Roman object. The experts made plenty of headlines, too, locating the earliest known cave paintings in South America, as well as what may be the oldest lipstick scientifically documented (in a daring red, no less).

Below are some of the most important art historical and archaeological discoveries of the year.

One of archaeology’s most fascinating mysteries began a new chapter when amateur archaeologists in England found a large Roman dodecahedron — one of 130 of the 12-sided ancient objects known in the world, but whose functions have been lost to time. Measuring 3 inches across, it’s one of the biggest examples to date, and “completely unique,” according to Richard Parker, secretary of the Norton Disney History and Archaeology Group, which located the object. “It’s complete, undamaged, and it clearly was considered of great value by whoever made it and by those that used it.” Absent of depictions in art or descriptions in literature, Roman dodecahedrons remain enigmas, but Parker believes it was a religious object. “It is quite a complex story to tell that we’re just starting to tease out,” he said.

Following “brat” summer courtesy of Charli XCX, autumn arrived with a new release from an unexpected musical throwback: Frédéric Chopin. The Polish composer, who died 175 years ago at age 39, has a new waltz attributed to him thanks to its discovery by a curator at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York; it’s his first unknown work found in nearly a century.

Chopin was a twentysomething when he composed the short but complete waltz on a postcard-sized manuscript. It may have been initially intended as a gift, but unlike his other known gifted waltzes, Chopin didn’t sign it, suggesting he may have changed his mind. To hear it for the first time “will be an exciting moment for everyone in the world of classical piano,” said Robinson McClellan, the curator who discovered it, in a statement in October.

Just before Halloween, the charity English Heritage, which manages a number of historic sites around the UK, announced an appropriately spooky find: a “staggering array” of witches’ marks had been discovered on the walls of a Tudor manor house in Lincolnshire. The carvings, formally known as apotropaic marks, were discovered by an English Heritage volunteer and are believed to date back to the turn of the 17th century.

With many of the symbols found in the servants’ wing, they include circles aimed to trap demons as well as overlapping Vs, which could have been a call to the Virgin Mary for divine protection. The name of the manor’s former owner appears as well, but upside down — as a possible curse on him.

In 1962, an Italian junk dealer found a rolled-up canvas in the basement of a villa in Capri, depicting an asymmetrically painted woman in a blue dress. Not giving the signature much thought, he framed it and gave it to his wife, who did not find it to her liking. Still, it hung in their family home and a restaurant they owned for decades. Now, experts believe it’s an original Picasso worth €6 million ($6.6 million) — and one of many portraits of the photographer Dora Maar, his lover — after a long effort by the junk dealer’s son, Andrea Lo Rosso, to authenticate the artist’s signature.

His father died in 2021 without seeing a resolution, and the Picasso Foundation in Paris has yet to authenticate the work. The painting has been in a vault for several years, but according to Lo Rosso, has survived unlikely odds since it was found with another anonymous work in the Capri basement.

“Both were covered with earth and lime and my mother spread them out and washed them with detergent, as if they were carpets,” he told CNN.

An auctioneer in London found 10 signed Salvador Dalí lithographs during a routine antiques assessment — after they had been forgotten for 50 years in the owner’s garage. The anonymous owner bought them during a gallery’s closing-down sale in the 1970s, recounted Hansons Richmond associate director Chris Kirkham, who discovered the works.

“It felt quite surreal. You never know what you’re going to uncover on a routine home visit,” he said on the auction’s website.

The lots all exceeded their estimates of £500-700 ($636-891) each when they went under the hammer in September, bringing in a combined £19,750 ($25,158).

A marble sculpture of the Greek god Hermes was stashed some 1,600 years ago in a sewer — and only turned up this past summer. Bulgarian archaeologists made the fortuitous find in July, per Reuters, during a dig at the site of the ancient city of Heraclea Sintica in Bulgaria, near its border with Greece.

The well-preserved statue is 6.8 feet tall and was likely placed in the sewer system under soil to protect it following an earthquake in A.D. 388, according to archaeologists leading the excavation. After the earthquake caused the decline of the city, it was abandoned around A.D. 500.

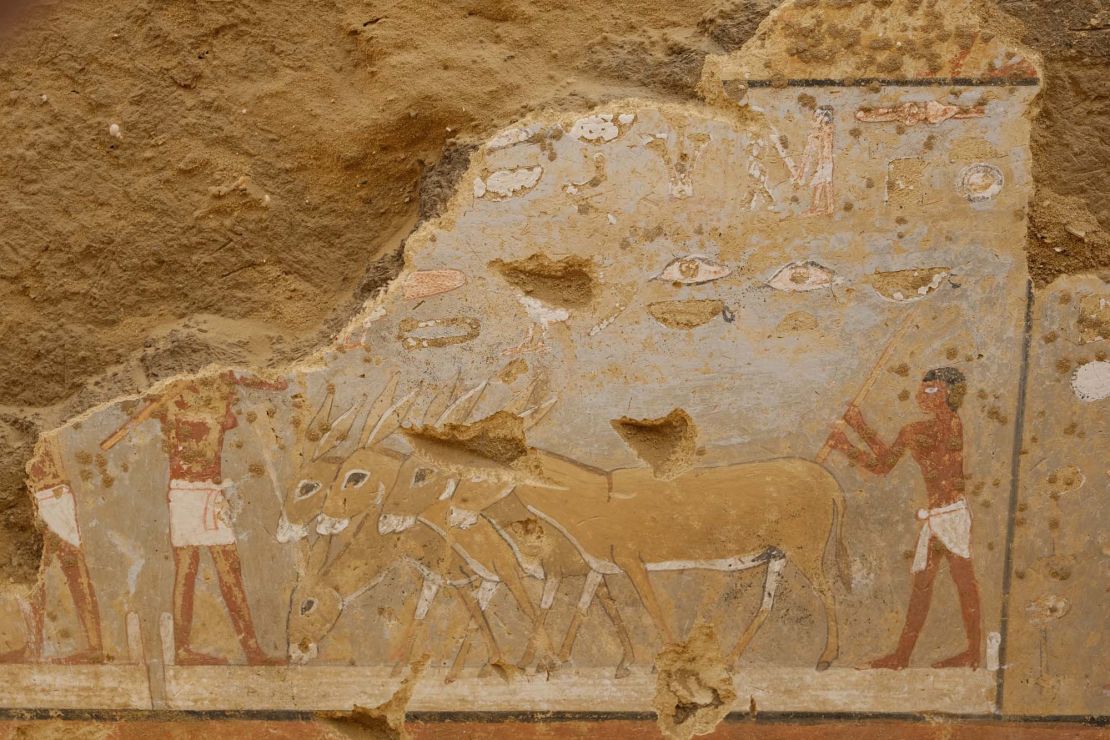

A tomb more than 4,300 years old revealed a window into the era’s daily life when archaeologists found a series of colorful paintings inside. Known as a mastaba, the tomb is located in the pyramid necropolis of Dahshur, which the German Archaeological Institute Cairo has been excavating since 1976. Inscriptions on a limestone false door to the mastaba reveal it belonged to an administrator named Seneb-nebef and his wife, Idut, and archaeologists have dated it to approximately 2,300 B.C..

Describing the paintings of people and animals as having “elegant forms and perfect execution,” Stephan Seidlmayer, who led the expedition, told CNN at the time that “the pictures offer valid evidence of the artistic milieu of the capital region of the developed Old Kingdom.”

A construction worker had the surprise of his life when he accidentally turned up a marble head of a woman while building a parking lot at a 16th-century country estate in Peterborough, England. It turned out to be an 1,800-year-old Roman sculpture. But that wasn’t the only surprise — the mysterious headless lady’s statuesque body turned up nearby when archaeologists began to work on the site two weeks later.

It’s now believed the estate’s 18th-century owner, Brownlow Cecil, the ninth Earl of Exeter, brought the sculpture back during an Italian tour in the 1760s — but how it wound up buried in the dirt remains a mystery.

A tiny vial found in southeastern Iran has shown that your favorite MAC lip color may not be too far off from its predecessor — 4,000 years ago. The stone vessel containing a deep red mixture of minerals — primarily hematite, along with manganite, braunite and vegetable-based waxy ingredients — is “probably the earliest” example of lipstick to be scientifically analyzed, researchers reported in February.

“Both the intensity of the red coloring minerals and the waxy substances are, surprisingly enough, fully compatible with recipes for contemporary lipsticks,” the study’s authors noted in the journal Scientific Reports.

They added that the shape of the vial and its ingredients suggested its use on the lips, but it’s also possible it was used in other ways. A lipstick-blush combination kit? An ancient girl had options.

Nearly 700 miles southwest of Buenos Aires, archaeologists from Argentina and Chile discovered the earliest known cave paintings in South America. Dating back 8,200 years, the 895 works of art come from the Huenul 1 cave, a mammoth rock shelter of around 6,700 square feet.

The scientists dated four black charcoal patterns within the system, which showed they were repeated for a period of at least 3,000 years. The cave art sheds light on the artistic ability and communication between hunter-gatherers during the middle Holocene period.

Other cave systems in the region could contain older art, said Dr. Guadalupe Romero Villanueva, who authored the research, but they have not been precisely dated, such as Argentina’s Cueva de las Manos, believed to host paintings dating back 9,500 years.

In January, a playground construction project in Naples, Italy, took a turn when it unearthed the ruins of a 2,000-year-old beach house with a potentially legendary owner. The once lavish cliffside mansion, featuring 10 spacious rooms, tiled walls and sprawling terraces, dates back to the 1st century and has been partially flooded by the sea due to repeated volcanic activity that sank the land.

Experts say its resident could have been the famed natural philosopher and naval leader Pliny the Elder, who commanded the fleet of 70 ships at the nearby Roman port at Misenum.

“It is likely that the majestic villa had a 360-degree view of the gulf of Naples for strategic military purposes,” Simona Formola, lead archaeologist at Naples’ art heritage, told CNN at the time. “We think (the excavation of) deeper layers could reveal more rooms and even frescoes — potentially also precious findings.”

The Canadian mining company Lucara Diamond Corp. announced in August that it had unearthed what it believed to be the second-largest diamond ever found, at 2,492 carats. The stone was found in the Karowe mine in Botswana, where the current second place record-holder was found in 2015 — the Lesedi La Rona, a 1,109-carat stone that sold for $53 million two years later. (The largest known diamond in the world is the 3,106-carat Cullinan Diamond, found in South Africa in 1905).

The mining company used an aptly named tool for the job: the Mega Diamond Recovery (MDR) X-ray Transmission (XRT) machine, which was developed to seek out and recover the world’s still-hidden gargantuan gemstones.

A British fine-art researcher made a startling discovery when he happened to spot a distinctive painting of the Tudor monarch Henry VIII in the background of a photograph posted to X. The image showed a reception in Warwickshire, England, in the building complex where the Warwickshire County Council is based. There, behind the smiling guests, Adam Busiakiewicz spotted a portrait with a “distinctive arched top.” It looked to be from a set of 22 portraits of significant kings, queens and public figures commissioned during the 1950s, many of which had been scattered following private auctions.

In a press release sent to CNN, Busiakiewicz said the arched top was a “special feature of the Sheldon set,” while the painting’s frame was “identical to other surviving examples.” The majority of the works, he added, “remain untraced to this day.”

A small home in Pompeii came with a big surprise when it was revealed it contained a number of ornate and erotic frescoes. Archaeologists uncovered the house in the central district of the ancient city, which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in AD 79 but preserved under layers of ash. Though tiny and lacking some of the architectural features of larger Roman dwellings, like the central open-air atrium, the home shows that even modest houses could have elaborate decor. The mythical scenes depict the goddess of love, Venus, with her mortal lover, Adonis, as well as Hippolytus, son of Theseus, who rejected his stepmother Phaedra’s romantic advances.

The discovery wasn’t the only set of impressive frescoes discovered in Pompeii this year: In the spring, archaeologists excavated a banquet hall with striking black-painted walls that feature an array of mythological characters associated with the Trojan War.

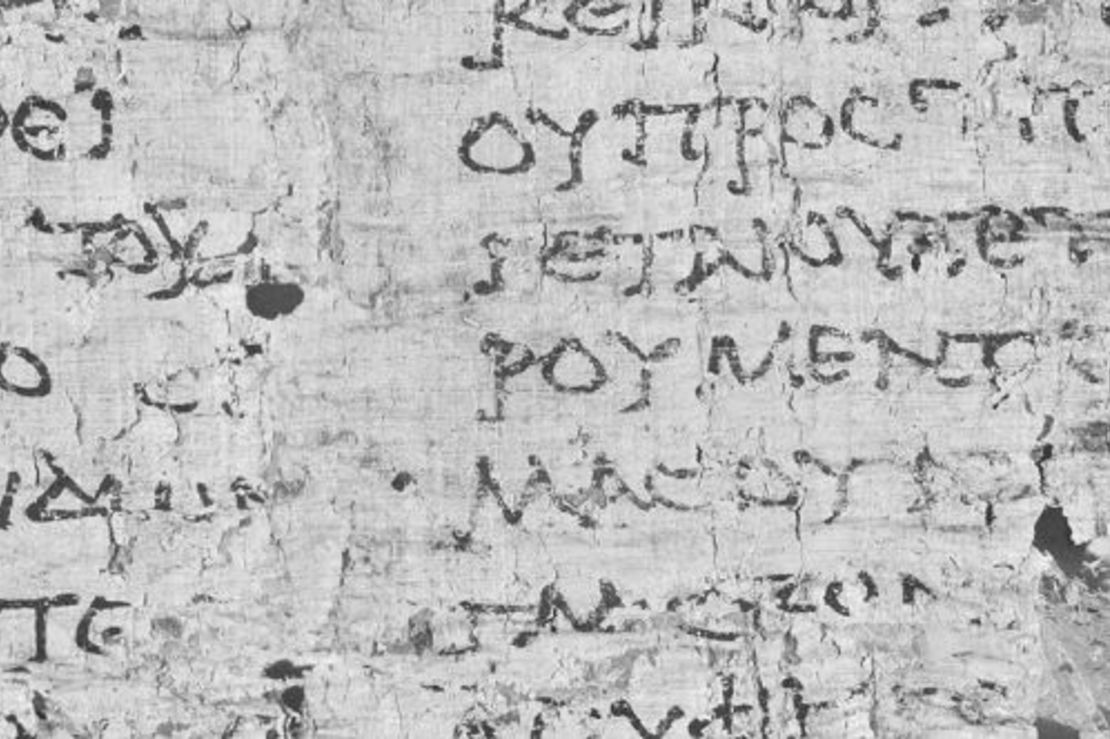

New Plato lore has been discovered in charred papyrus scrolls thanks to AI, according to Italian researchers, who have been examining a set of scrolls that were buried under volcanic ash in Pompeii. The newly deciphered text is part of 1,800 carbonized scrolls discovered in the 18th century, known as the Herculaneum scrolls. Researchers have been using AI along with other specialized imaging technology to read the scrolls, which are partially destroyed.

So what are the new details? The Greek philosopher’s final resting place, for one — a secret garden near a sacred shrine inside the Platonic Academy of Athens (which was destroyed in 86 B.C.). And there’s gossip as well: Plato had been said to enjoy the music played to him on his deathbed, but the scrolls say otherwise. He found the flute music had a “scant sense of rhythm,” experts said during a presentation in Naples this past spring.