An archeological missing person’s case has gotten a bit more complicated. Scientists have learned that a skull that long-believed to be that of Cleopatra’s sister Arsinoë IV actually belonged to a young boy. A team from the University of Vienna and Austrian Academy of Sciences analyzed the skull and found that the boy was likely between 11 and 14-years-old and suffered from an unknown developmental disorder. A genetic analysis also revealed that he was likely from Italy or Sardinia. The findings are detailed in a study published January 10 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Who was Arsionë IV?

Arsinoë IV was the youngest daughter of king Ptolemy XII Auletes of Egypt. She was the sister of Queen Cleopatra VII and the kings Ptolemy XIII and XIV. Arsinoë attempted to lead Egyptian forces against Cleopatra, who had allied herself with Julius Caesar and the Romans during the Alexandrian war. At the request of Mark Antony–a Roman politician and Celopatra’s lover–Arsinoë was murdered in Ephesos, Turkey sometime around 41 BCE.

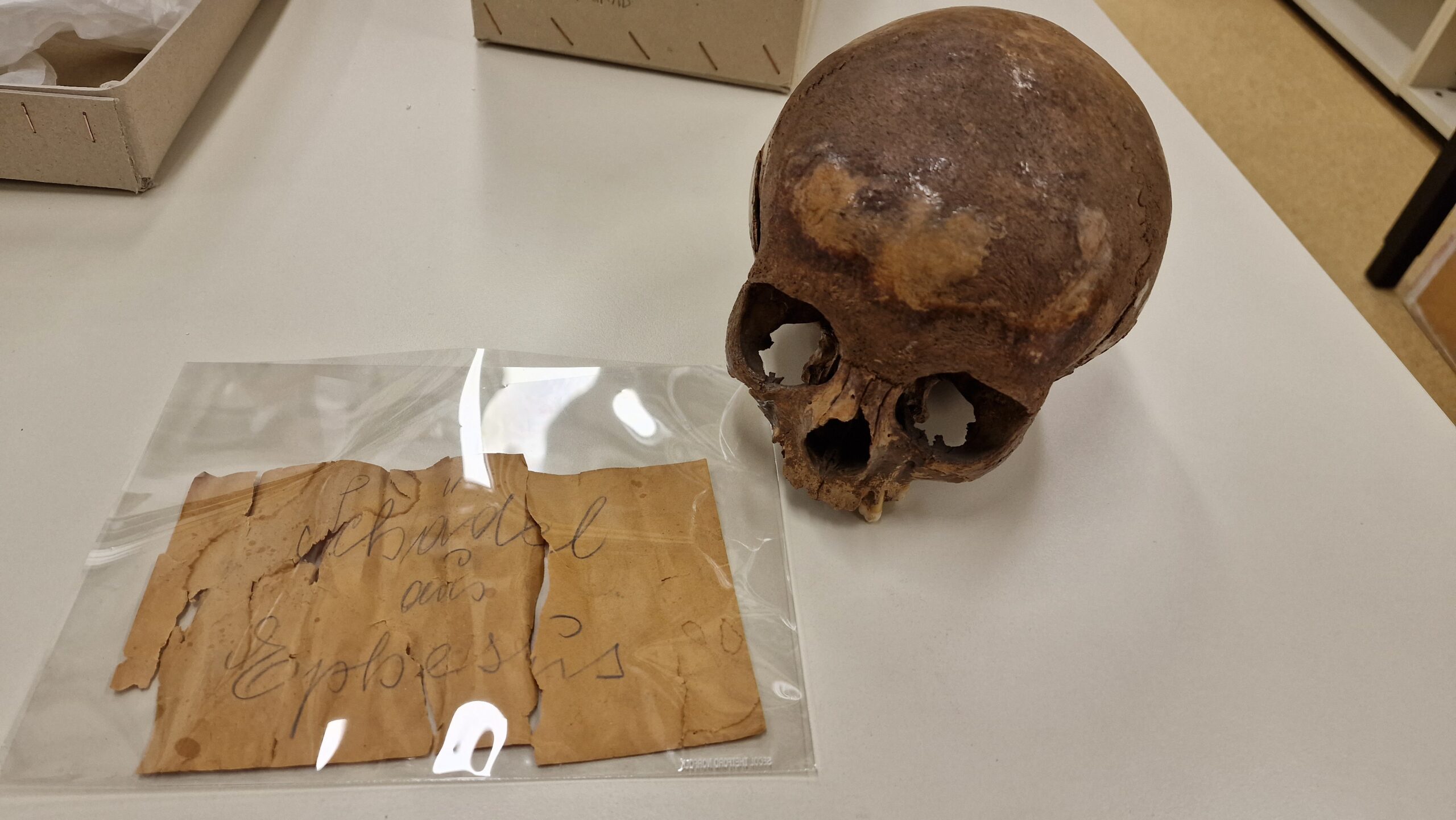

In 1929, a skull was found in Ephesos, Turkey by Austrian archaeologist Josef Keil and his team. They found a sarcophagus that was completely filled with water in the ruins of a once elaborate building called the Octagon in Ephesos. While they didn’t find any goods in the grave, there was a complete skeleton. Keil took the skull with him before the researchers closed the tomb.

[ Related: Archaeologists find the 4,000-year-old tomb of an overachieving Egyptian magician. ]

The initial analysis in Greifswald, Germany proposed that the grave belonged to “a very distinguished person” and probably a woman that was about 20-years-old Keil couldn’t provide any hard data, but the skull made it to Austria when he began a new job at the University of Vienna. Weninger published an article in 1953 with photos and measurements and concluded that the skull represented a young woman who was of a “refined, specialised type.”

In 1982, the rest of the skeleton was found in Ephesos. However, it was not found in the sarcophagus. The bones were in a niche in an antechamber of the burial chamber. A combination of archaeological records and the fact that Arsinoë IV was murdered in Ephesos around 41 BCE led archeologists and anthropologists to a new hypothesis in 1990. Arsinoë IV may have been buried in this elaborate tomb in Ephesos.

A chromosomal surprise

In this new study, a team of geneticists, orthodontists, dating specialists, and archeologists took a closer look at this skull. First, they used micro-computed tomography to create a very detailed digital image of the skull as an archival record. They then took tiny samples from the base of the skull and the inner ear to determine how old the person was when he or she died and obtain some DNA.

They found that the skull dates to between 36 and 205 BCE, which corresponds well with the traditionally accepted date of death of Arsinoë IV (41 BCE). The geneticists also found a match between the skull and some samples from the femur. This means that the second skeleton that was later found in the anteroom actually belonged to the same person as the skull that Keil had removed from the sarcophagus in 1929.

“But then came the big surprise: in repeated tests, the skull and femur both clearly showed the presence of a Y chromosome–in other words, a male,” study co-author and University of Vienna archeologist Gerhard Weber said in a statement.

The micro-CT data and closer study of the skull revealed that the boy from the Octagon was still in his puberty and was around 11 to 14-years-old. High-resolution images of the dental roots and the still developing skull base confirmed that this was a young teen. He also likely suffered from some sort of disease affecting his skull. One of his cranial sutures, which normally fuses at the age of 65, was already closed and gave the skull a very asymmetrical shape.

[ Related: A gold-laced mummy could be the ‘oldest and most complete’ specimen found in Egypt. ]

According to the team, the most striking feature was the underdeveloped upper jaw. This is unusually angled downwards, but was more upwards and likely led to major problems with chewing. They looked at various dental joints and the two teeth remaining in the jaw to confirm this. While the first permanent molar did not show any signs of being used to chew food, the first premolar was chewed down and had clear cracks from overloading. The team believes that there was no regular tooth contact, a consequence of the jaw and face growing in an unusual way. While it is still unclear what led to these grown disorders, it may have been a vitamin-D deficiency or a genetic syndrome such as Treacher Collins syndrome.

For archaeologists and anthropologists, the search for Arsinoë IV’s remains can continue, without this rumor that her skull had already been found.