“I don’t care.” These words uttered by a woman with striking blue hair command attention. Her vivid crimson lips contrast sharply, directing the gaze to her face and amplifying the emotional depth of the scene. With her mouth agape and eyes shut, the weight of stress etches her features, massive tears cascading down her cheeks. Her face and a hand teetering on the brink of submersion beneath stylized waves.

“I don’t care. I’d rather sink than call Brad for help,” the drowning woman proclaims, embracing her fate. Whether the woman said it with anger, defiance or resignation, the painting’s viewer can only guess.

Drowning Girl, an exemplary piece symbolic of the Pop Art movement, holds a prominent place in Roy Lichtenstein’s oeuvre. Acquired by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1971, this 1963 painting, rendered in oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas, is now on show at an Albertina retrospective, which runs through July 14.

Roy Lichtenstein, a luminary of the Pop Art movement alongside Andy Warhol, would have celebrated his hundredth birthday last October. His legacy reverberates through the annals of 20th-century art history, leaving a lasting mark on the creative landscape.

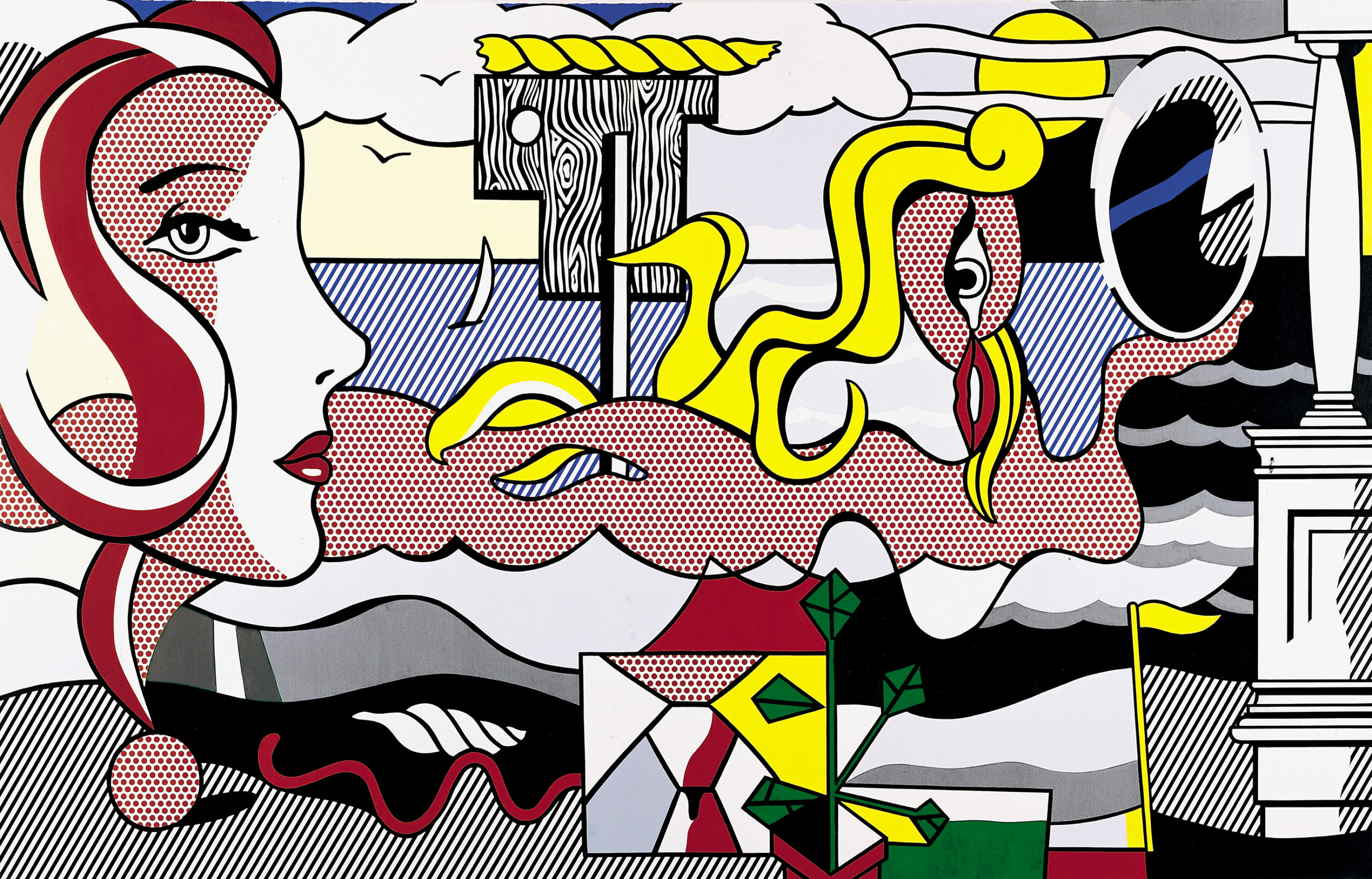

At the heart of Pop Art, Lichtenstein adeptly appropriated and reimagined iconic symbols, from Mickey Mouse to love and war comics, to popular advertising motifs. Through his masterful reinterpretations, he challenged conventional notions of high and low culture, inviting viewers to reconsider the significance of everyday imagery in the realm of art.

His distinctive style, characterized by the utilization of Ben-Day dots, infused these familiar images with irony, challenging societal constructs of femininity and masculinity entrenched within the post-war consumer landscape. His artworks served as a poignant commentary on the burgeoning American women’s, anti-Vietnam, and anti-nuclear movements, reflecting the zeitgeist of the era.

During the inauguration of the exhibition, Albertina director Klaus Albrecht Schröder remarked on Lichtenstein’s art, stating, “In the 1960s, at the height of abstract expressionism, Roy Lichtenstein returned to representational, self-reflective art and, with a lot of irony, broke down the boundaries between high art and everyday culture.”

In addition to his exploration of American visual culture, Lichtenstein delved into meta-artistic realms, crafting pieces that scrutinized the essence of art itself. Through the magnification of brushstrokes and reinterpretation of works by Monet, Picasso, and Matisse, he metamorphosed impressionistic strokes and renowned compositions into simplified yet compelling forms reminiscent of illustrations. This multifaceted approach underscores Lichtenstein’s profound engagement with artistic traditions, reshaping the contours of contemporary art.

From low art to high art

Renowned for cutting out the comic from its source and employing an opaque projector to overlay the initial drawing on his canvas, Lichtenstein would trace the basic image, and then proceed to reinterpret it, selectively removing certain elements whilst accentuating others.

“He was the first to translate a cartoon into a monumental format and thereby do something new in terms of content. He explains the most unartistic thing there is, namely low art of comics, to high art,” says Schröder.

Lichtenstein pondered the ramifications of challenging an audience’s assumptions about comic strips by elevating them to the realm of high art. This transformation countered the very nature of comic strips as disposable commodities.

SEE ALSO: An Exhibition of Sonia Delaunay’s Work Holds a Mirror to a Life Lived in Art

Art historian Tamar Avishai delves into this inquiry in her Lonely Palette podcast episode 27, examining Lichtenstein’s Oh, All Right from 1964, which fetched $42.6 million at a Christie’s auction in 2010. The pop artist’s depiction of a pouty redhead was formerly in the possession of actor and art collector Steve Martin and American casino magnate Steve Wynn.

“What happens when you take away the punchline and give it back some ambiguity,” she asks, concluding “How brilliant a storyteller Lichtenstein really is, how deft he was at picking the perfect moment of narrative ambiguity.”

Consider Drowning Girl as an example. Originally, her dialogue was, “I don’t care if I have a cramp,” a line condensed by Lichtenstein to the enigmatic “I don’t care.” In Tony Abruzzo’s original strip, her blonde, bewildered boyfriend is portrayed on a capsized boat in the background, implying his fault for the dramatic scene.

“He consistently replicates the speech bubbles; he doesn’t craft new ones. It’s real appropriation. He trims the text down, condenses it, inevitably reaching the core, and it’s always about Brad—yet the rationale remains elusive,” observes Gunhild Bauer, the exhibition’s curator.

Lichtenstein’s cropped version underscores his knack for positioning himself at the narrative center, akin to the pivotal panel of a comic strip. By leaving the story’s beginning and end ambiguous, Lichtenstein invites viewers to engage their imaginations to fill in narrative gaps.

Copycat criticism

Despite acclaim, not everyone viewed Lichtenstein’s work in the same light. His methodology and outcomes often drew accusations of plagiarism. In response to criticism, Lichtenstein contended that he wasn’t simply copying but rather reinterpreting the original content through a different lens.

While cartoonist Art Spiegelman said Lichtenstein did no more or less for comics than Andy Warhol did for soup, Hugo Frey and Jan Baetens offer a contrasting perspective in their essay “Comics Culture and Roy Lichtenstein Revisited: Analyzing a Forgotten Feedback Loop” in volume 42 of Art History, showing that the comics community was looking to benefit from Lichtenstein’s fame. Furthermore, the authors explain that the loop included a strong economic impulse, redirecting comics towards a new, adult readership.

According to Frey and Baetens, popular comic book series underwent a transformation, evolving into elongated paperbacks crafted to emulate the vibrant aesthetics of Pop. This transformation was achieved through the incorporation of pop-themed advertising blurbs, innovative dust jacket designs, and a fresh approach to page layout within the content.

As examples, the authors mention Marvel’s ‘Marvel Collector’s Albums’, published by Lancer Books in the United States, which introduced six distinct paperback volumes inspired by Pop Art, featuring iconic characters such as The Fantastic Four, The Hulk, The Mighty Thor and Daredevil.

Each of their covers employed intense images of the eponymous comic heroes, reminiscent of the core strategy of pop: the magnification of iconic imagery, while also removing or minimizing anything superfluous.

Similarly, the paperback “High Camp Superheroes,” scripted by Jerry Siegel, adopted much of the same pop-inspired style. Penned by the co-creator of Superman, this work was presented by its publisher, Belmont, in 1966 as a boldly innovative production infused with Pop Art allure.

Acknowledging some of the criticizing sentiments expressed by comic creators, Lichtenstein remarked during a speech at the National Cartoonist Society convention in April 1965: “I am honored and very much amazed that you are feeding me instead of stringing me up. I think a good part of the art-world believes I am poking fun at cartooning rather than at art—which is much closer to the truth.”

He also noted that “the only hint of a lawsuit in this connection has come from a fine art source and not from cartoonists.”

Sculptures, more or less

The Albertina retrospective was developed in collaboration with the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, founded by Dorothy Lichtenstein after her husband’s passing. In 2023, the museum received a substantial donation from the foundation, consisting of 95 Lichtenstein sculpture works, as well as related materials such as studies, collages, and various textile and ceramic projects.

The generous contribution effectively establishes a Lichtenstein sculpture study collection in Europe, paralleling similar donations recently made to the collaboration between the Nasher Sculpture Center and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Both the Albertina and the Foundation endeavored to spotlight Lichtenstein’s lesser-known sculptural works at the centennial exhibition. The showcased brushstroke sculptures have seamlessly joined the Albertina collection. Originating from this generous donation, a towering two-meter-high brushstroke sculpture is currently exhibited at Albertina Klosterneuburg, the museum’s recently revealed third venue dedicated to large-scale modern and contemporary art, inaugurated this April. Within one of its halls and the adjacent garden, the spotlight is squarely focused on sculptures.

Some sculptures featured in the centennial exhibition, crafted from expensive bronze, underwent a painting process that obscured their bronze origins, resulting in a nearly plastic-like appearance and the loss of their three-dimensional essence.

“Only upon physical contact does the coldness of the material reveal its true composition as bronze,” elaborates curator Bauer.

“They metamorphosed into caricatures of sculptures, essentially becoming non-sculptures,” she adds, highlighting Lichtenstein’s inclination to cast only sculptures that had already been sold. Consequently, very few editions remain, with some models left uncased.

Bauer notes that Lichtenstein deviated from the traditional aura associated with a work of art and its material, deliberately manipulating it. “He played with it, making it resemble a cheap, mass-produced object,” the art expert explains. “In doing so, he critiques an aesthetic driven solely by economic considerations, divorcing art from its intrinsic value.”

Lichtenstein beyond the canvas

Amidst the close bond between the Albertina and the Foundation, Dorothy Lichtenstein and the Foundation’s executive director Jack Cowart, an art historian specializing in Henri Matisse and Roy Lichtenstein, attended the exhibition’s opening in Vienna.

Cowart characterizes Lichtenstein as a forward-thinking artist, continuously focused on creating tomorrow’s art without dwelling on the past.

“Roy was always two steps ahead of where he was at the present. Connecting all of his media, he’s more than just a painter. He’s an artist who had all the graphic sensibility in design,” Cowart tells Observer. “But if he’s painting, he’s thinking about making prints. If he’s printmaking, he’s thinking about making objects. He was always going back and forth, and he’s always worked for an aesthetic unity.”

Despite his ambition to create significant art, Lichtenstein remained modest, willing to accept with a simple “I tried” if his work went unappreciated. Cowart paints a nuanced picture of Lichtenstein’s personality, describing him as reserved yet subtly humorous, patient and kind.

“He wasn’t shy, but very reluctant and quiet. He didn’t make jokes, he just made observations.” This demeanor, Cowart believes, aligns with Lichtenstein’s artistic ethos.

Amidst a resurgence of interest in comics and the transformative impact of digital mediums on the art world, Dorothy Lichtenstein and Cowart envision a diverse audience engaging with Lichtenstein’s art on their terms, rejecting the notion of a singular “correct” interpretation.

They hope that Lichtenstein’s legacy will endure, echoing his sentiment: “When the last person cares, turn out the light and go home. You don’t owe me anything.”

“Roy Lichtenstein: A Centennial Exhibition” is on view at the Albertina in Vienna through July 14.