A dear friend of mine died recently of a sudden heart attack. I discovered that the only music I found consoling was the slow movement of Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto – the 1929 recording with the composer at the piano, accompanied by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra.

I am of course aware that many people find this piece maudlin. But Rachmaninoff the pianist is never maudlin. He projects sadness with implacable poise. His expressive inflections are never momentary inspirations; they are governed by a designated template of feeling. He projects a sovereign personality as admirable and imposing as any I can think of in the creative arts.

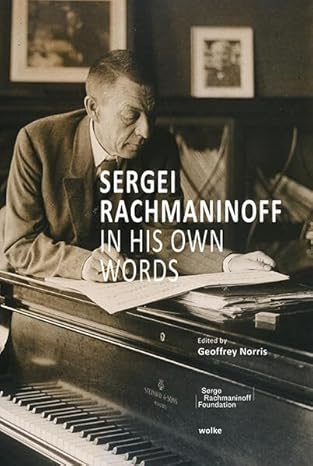

A new book of Rachmaninoff’s essays and interviews – Sergei Rachmaninoff In His Own Words, edited by Geoffrey Norris – amplifies these observations. I even discovered Rachmaninoff writing about that 1929 recording. But nothing in the book stirred me as profoundly as its preamble. In 1932, Rachmaninoff was one of more than a hundred individuals invited to define “music.” He responded with seven lines in Russian. Translated, they read:

What is music? How can one define it?

Music is a calm moonlight night; a rustling of summer foliage; music is the distant peal of bells at eveningtide. Music is born only in the heart and it appeals only to the heart. It is love!

The Sister of music is Poetry and the Mother is Sorrow!

In the articles and interviews here assembled, Rachmaninoff also testifies that he approaches music “from within.” He writes: “Music should bring relief.” Conducting an orchestra, he experiences an “inner calm”; it reminds him of “driving a motorcar.”

The 1929 concerto recording with Stokowski is a supreme collaboration. Their exchanges are seamless, clairvoyant. Unlike the mix in many modern recordings, the piano is never an exaggerated presence – and Rachmaninoff delights in circulating under the orchestra, then mercurially arising. In the Adagio sostenuto second movement, the famous Stokowski legato – a lava flow – is an ideal medium of expression. The coda to the first movement is also exceptional, with Stokowski’s hyper-sensitive cellos inspiring Rachmaninoff’s sonic imagination. In Rachmaninoff in his Own Words, Stokowski’s orchestra is repeatedly praised as nonpareil. Of the recording of his Second Concerto, Rachmaninoff says (in The Gramophone, April 1931):

“To make records with the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra is as thrilling an experience as any artist could desire. Unquestionably, they are the finest orchestral combination in the world: even the famous New York Philharmonic, which you heard in London under Toscanini last summer, must, I think, take second place. Only by working with the Philadelphians both as soloist and conductor, as has been my privilege, can one fully realise and appreciate their perfection of ensemble.

“Recording my own [Second] Concerto with this orchestra was an unique event. Apart from the fact that I am the only pianist who has played with them for the gramophone, it is very rarely that an artist, whether as soloist or composer, is gratified by hearing his work accompanied and interpreted with so much sympathetic co-operation, such perfection of detail and balance between piano and orchestra. These discs, like all those made by the Philadelphians, were recorded in a concert hall, where we played exactly as though we were giving a public performance. Naturally, this method ensures the most realistic results, but in any case, no studio exists, even in America, that could accommodate an orchestra of a hundred and ten players.

“Their efficiency is almost incredible. In England I hear constant complaints that your orchestras suffer always from under-rehearsal. The Philadelphia Orchestra, on the other hand, have attained such a standard of excellence that they produce the finest results with the minimum of preliminary work. Recently, I conducted their superb recording of my symphony poem, “The Isle of the Dead”, now published in a Victor album of three records which play for about twenty-two minutes. After no more than two rehearsals the orchestra were ready for the microphone, and the entire work was completed in less than four hours.”

Two themes that pervade Rachmaninoff’s public discourse are American music education, which he finds inadequate, and modern music, which he disdains. He praises American orchestras and audiences unstintingly. He calls New York City the “musical capital of the world.” He appreciates the “bold private initiative” of the Boks, who fund the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Curtis Institute. But gifted American music students, he finds, are underserved. They cannot even afford to attend important concerts, because no tickets are set aside for them. And there is no national conservatory, no institutionalization of “the highest and the purest in music radiating from the center.”

(In Russia — including Soviet Russia — an integrated musical community of performers and composers, orchestras and conservatories instilled tradition. Nothing of that sort ever emerged in the United States – although Jeannette Thurber, in founding her National Conservatory of Music and in 1892 naming Antonin Dvorak to lead it, had that in mind. Thurber’s efforts to secure federal funding went nowhere. And Dvorak’s complaints about American music education forecast Rachmaninoff’s.)

In a 1925 Musical Courier article, we learn something pertinent about Rachmaninoff’s regard for another “radiating center” — Konstantin Stanislavsky’s legendary Moscow Art Theatre:

“Rachmaninoff is very devoted to the theatre. In his youth he was a great admirer of Chekhov. He is a friend of the players of the Moscow Art Theatre. I remember what a stimulating sight I saw one afternoon in the Artists’ room after a Rachmaninoff concert at Carnegie Hall, New York. There stood in a corner a huge glittering laurel wreath in green, gold and white, presented to the master pianist with the cordial greetings of the Moscow Art Theatre. The actors and actresses from the greatest theatre of the world led by stalwart and handsome Stanislavsky, almost surrounded him. Some of the men kissed him, and he them in real Russian style. They exchanged a few words in the tempo of a chant before an altar. Then for a minute or two they spoke not a word. The Moscow players simply looked at the great Moscow musician in reverent silence. Such devotion, such poise, such childlike sincerity, I never saw before, even on the stage of the Moscow Art Theatre. The actors surpassed themselves. Then they gently walked away one by one, like so many children, sad at parting from their playmate. The master’s gaze was fixed on them, and he waved at the last actor who looked back as he went out of the door. I watched this bit of drama in life with breathless wonder, and I am not ashamed to admit that the sanctity of the scene moved me to tears. And from the quick movement of his eyelids I could notice that the master’s eyes were not altogether dry either. I shall never forget this one act play of the Moscow Art Theatre, Rachmaninoff playing the part of the hero. It was more than a play, it was a sacrament.”

But perhaps the most abiding motif in Sergei Rachmaninoff In His Own Words is Rachmaninoff’s contempt for musical modernism. For him, beauty in music is an absolute criterion, and music’s supreme ingredient is melody. In this regard, he pursues a polemic whose best-known manifestation, in English-speaking countries, was once Constant Lambert’s Music Ho – A Study of Music in Decline (1934). Intolerant of Igor Stravinsky, Lambert’s anoints Jean Sibelius his contemporary composer of choice.

But Sibelius wrestled with modernism in his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, anxious and insecure, trying to catch up. Serge Prokofiev, too, strove to be a modernist in competition with Stravinsky. Then he called it quits, returning to Russia and his own Russian Romantic roots.

In 1930, Rachmaninoff revealingly recalled meeting Tchaikovsky “some three years before he died. . . . Tchaikovsky at that time was already world-famous, and honoured by everybody, but he remained unspoiled. He was one of the most charming artists and men I ever met. He had an unequalled delicacy of mind. He was modest, as all really great people are, and simple, as very few are. (I met only one other man who at all resembled him, and that was [Anton] Chekhov.)”

Judging from his interviews and essays, Rachmaninoff was never tortured by modernism. He never wrestled with its challenge to tradition. A man of firm identity and principle, he simply waited it out.

And his music prevails.

Related blogs: Rachmaninoff “the homesick composer”; Rachmaninoff’s valedictory “Symphonic Dances.”