SS Normandie only graced the seas for four years before meeting a fiery end. But it was long enough for her to be considered the ultimate ocean liner, profiled here as part of our Art Deco Centenary series.

Constructed by shipping company Compagnie Générale Transatlantique (CGT) in 1932, Normandie was France’s pièce de résistance in the arms race to see which European power could build the fastest, grandest transatlantic liner.

At the time, the steamship was the largest and the first to exceed 60,000 tons in weight and 1,000 feet (305 metres) in length – just short of the Eiffel Tower and significantly bigger than the Titanic.

Despite her heft, a revolutionary hydrodynamic hull and turbo-electric engine also made Normandie the fastest ship afloat, completing her maiden voyage from Le Havre to New York in May 1935 in just over four days.

At the time, the New York Times described her as “the greatest mass of steel and machinery ever to sail the sea”.

CGT aimed for Normandie to showcase “the genius of France” and gave the old guard of art deco carte blanche to design its interiors, with light fixtures by René Lalique, furniture by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and tea sets by Christofle.

Richly appointed in metal, marble and gold leaf, the ship became a floating equivalent of the seminal Exposition Internationales des Arts Decoratifs, which first introduced art deco to the world in 1925.

Normandie was “an ambassador” for France

All this unrivalled pomp came at an unrivalled cost of 812 million Francs ($60 million) – then the greatest amount paid for a passenger liner and heavily subsidised by the French government. According to Measuring Worth, that would equate to a $9 billion project today.

“The unprecedented cost of the construction and lavish decoration were justified in the midst of a worldwide financial crisis because the ship’s mission was to serve as an ambassador, carrying the art and glory of France to foreign lands,” explains the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ocean liners were the ultimate icons of the machine age, which art deco hoped to capture, symbolising speed, glamour and a new era of international travel.

And Normandie was perhaps the most emblematic of them all, although she only sailed for four and a half years before succumbing to the horrors of world war two – much like art deco itself.

“SS Normandie was the ultimate transatlantic ocean liner – assuredly of the 1930s, but perhaps of the entire 20th century,” wrote Maritime author and historian William H. Miller.

“Her French creators, designers and decorators sought perfection and then, or so it would seem, went one step further.”

Revolutionary hull design was deemed “too radical”

Normandie was completed in the French port city of Saint-Nazaire on 29 October 1932, exactly three years after the Wall Street Crash that spawned the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialised world.

The steamship’s iconic silhouette with its concave, clipper-style bow was the work of Vladimir Yourkevitch, a Russian naval architect who had moved France following the October Revolution.

Yourkevitch gave the ship a brand new style of hull, with a bulbous forefoot underneath the waterline that reduced drag and helped Normandie achieve its record-breaking speeds.

The design was so ahead of its time that CGT’s British counterpart Cunard White Star reportedly turned it down for being “too radical”, although it would eventually become the standard for large ocean-going vessels by the 1960s.

Above the water, too, Normandie was designed for speed, with the heavy machinery that would usually clutter the exterior hidden below deck for improved aerodynamics.

This created the ship’s iconic streamlined silhouette – immortalised in a poster by graphic designer Cassandre, which itself became one of the defining works of art deco.

“It was a floating museum”

The largest portion of Normandie’s 1,972 tickets – and most of her public spaces – were dedicated to first-class guests in a bid to lure in wealthy American tourists.

Among them was an ornate Byzantine chapel, a winter garden with exotic birds, a shooting gallery, the first ever theatre on an ocean liner and an indoor swimming pool with its own bar, both blanketed in tiled mosaics.

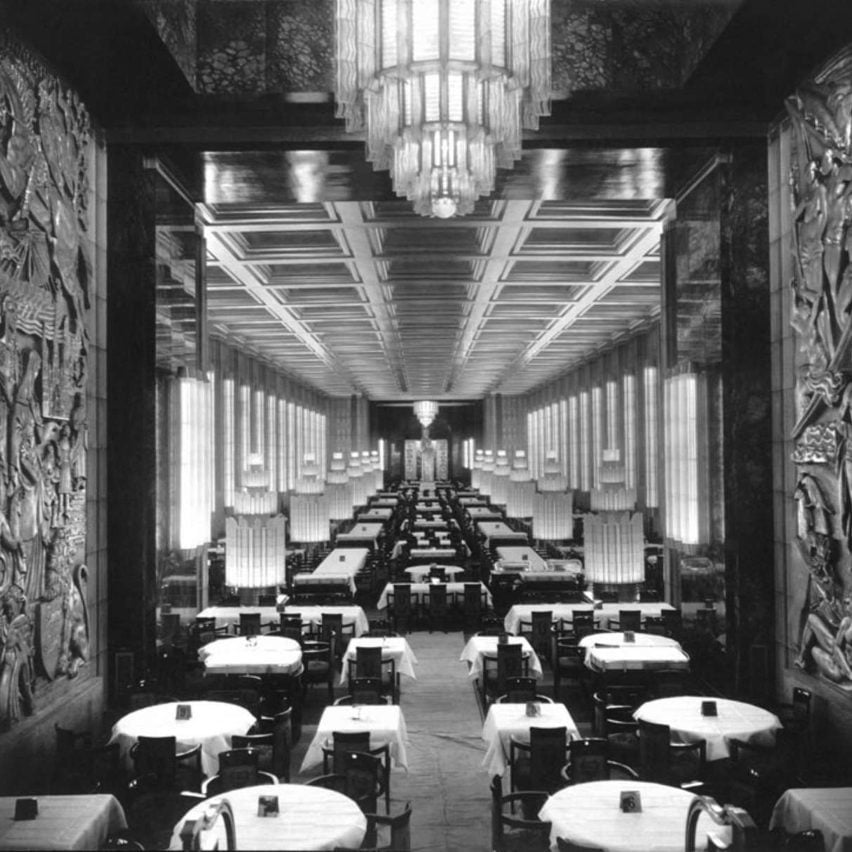

The first-class dining hall was the largest room on any ship at the time. At 300 feet (91 metres), it was famously longer than the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles and equally as opulent, fitted with dramatic bronze bas-reliefs by sculptor Raymond Delamarre and Lalique lighting columns.

It marked one of the first times that electric lighting was integrated into an architectural structure, glinting off its many reflective surfaces and earning Normandie the nickname “Ship of Light”.

Not to be surpassed, the triple-height Grand Salon featured 20-foot (six-metre) doors inset with bronze medallions by metalworker Raymond Subes and gilded glass murals by artist Jean Dupas – parts of which are today held in the collection of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“It was a floating museum,” said Bruce Newman, founder of New York antique gallery and auction house Newel, when he put the Dupas murals under the hammer in 1984.

Unsurprisingly then, Normandie proved popular among the rich and famous, carrying aristocrats and Hollywood royalty like Cary Grant and Marlene Dietrich across the Atlantic alongside cultural luminaries from Salvador Dalí to Ernest Hemingway.

However, Normandie’s art deco grandeur and overemphasis on first-class amenities are also credited with ultimately harming her attendance, creating an impression that the ship was out of reach for the average person despite offering plenty of tourist and third-class tickets.

With coffers squeezed by the Great Depression, Normandie often travelled at less than 50 per cent capacity while passengers flocked to rival liners such as Cunard White Star’s more demure RMS Queen Mary.

“The Normandie was the most extravagant, luxurious, and celebrated liner of her time,” explained the late maritime historian Everett Viez.

“But the Normandie was most likely too luxurious, too art deco extravagant. Comparatively, the Queen Mary was less glamorous, possibly less stunning, and certainly less pretentious.”

Not with a bang but with a whimper

Normandie found herself harboured in New York when Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, having arrived in the city just four days prior.

To avoid being torpedoed by German U-boats, she languished here until America entered the war in 1941 and the US Navy seized the ocean liner to be converted into a troopship for 15,000 soldiers under the name USS Lafayette.

But a string of bad luck meant the ship would never sail again. On 9 February 1942, as the retrofit was underway, a rogue spark from a welding torch set the ship ablaze and the vast amounts of water pumped on board by firefighters caused her to capsize and sink to the bottom of the Hudson River.

A massive, $4.5 million salvage operation over 17 months eventually saw her dredged up and righted the following year. But the damage was deemed too severe and costly to repair amid the financial strain of the war, so the world’s greatest ocean liner was sold for scrap metal in 1946 for only $161,000 – equivalent to $2.6 million in today’s money.

Thankfully, Normandie’s art deco trimmings had been removed before the fire and are now spread across private collections, hotels, cruise liners and museums such as the Met, and are considered some of the most important examples of the style.

The ship’s metal components, meanwhile, were shipped to Pennsylvania and melted down to create building supports and car parts, becoming part of America’s industrial lifeblood.

“In a very real way, then, Normandie is still with us, spread out all over America, being recycled again and again, her identity gone forever,” reporter Sam Roberts wrote in the New York Times.

All images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Art Deco Centenary

This article is part of Dezeen’s Art Deco Centenary series, which explores art deco architecture and design 100 years on from the “arts décoratifs” exposition in Paris that later gave the style its name.

The post Ill-fated art deco ocean liner SS Normandie was "too luxurious" for her time appeared first on Dezeen.