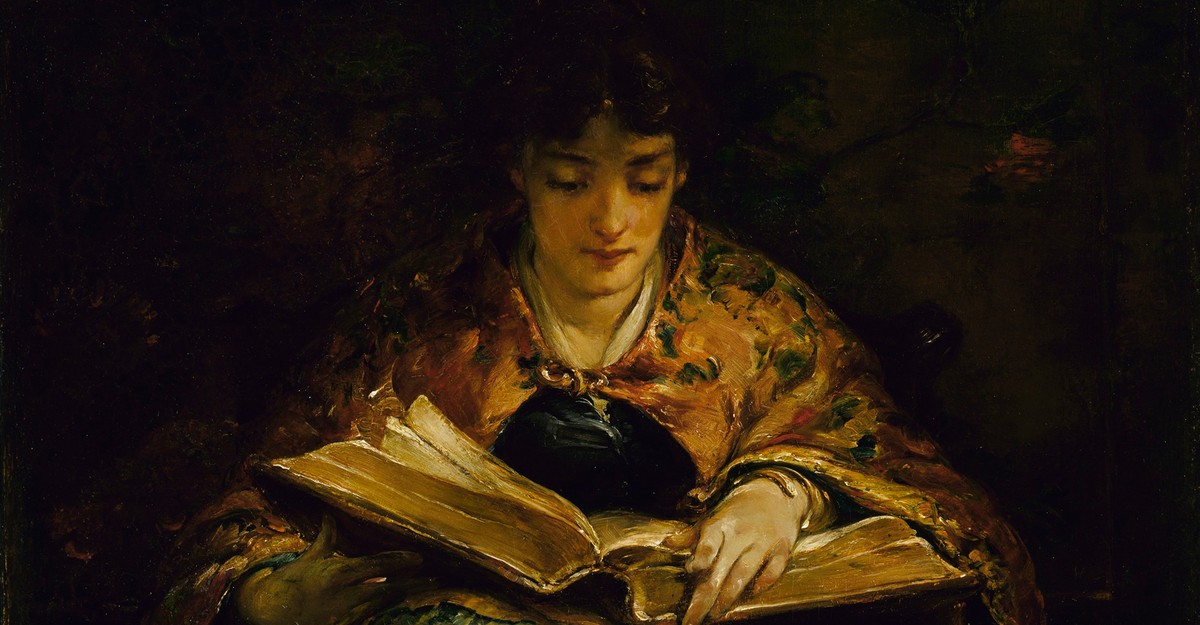

Many friends of mine are pretty deep in the slough of despond. I occasionally plead with them to make their predictions of catastrophe less hopeless and categorical, but with less success than I wish. I respect their points of view but have decided to look elsewhere for advice, and so have turned to a different set of friends—those sitting on my bookshelves.

Some of these friends have been with me for more than half a century; and they get wiser and more insightful with age. One of the first I turned to is only slightly older than I am: Motivation and Personality, by the academic psychologist Abraham Maslow. The book has a family history: Maslow summered at a lake in Maine in a cabin near one owned by my grandfather, a self-made shoe-factory owner who came to the United States with only the benefit of a grade-school education.

The story goes that Maslow was complaining about his inability to finish writing his magnum opus while surrounded by the clamor of kids and holiday-makers. After a couple of days of this, Sam Cohen turned to him, told him that writing was a job like any other, and that he had set aside an office for him in his factory, and then he ordered (rather than invited) him to go there and finish the book. Maslow did, and I have the author’s inscription on the title page to prove it.

Maslow thought that psychology had focused excessively on the pathological; he was interested instead in what made for psychological health—a deeper and truer objective, to my mind, than the contemporary quest for happiness, which tends to be ephemeral and occasionally inappropriate to our circumstances.

Here are two relevant bits:

Since for healthy people, the unknown is not frightening, they do not have to spend any time laying the ghost, whistling past the cemetery or otherwise protecting themselves against imagined dangers. They do not neglect the unknown, or deny it, or run away from it, or try to make believe it is really known, nor do they organize, dichotomize, or rubricize it prematurely.

And then this:

They can take the frailties and sins, weaknesses, and evils of human nature in the same unquestioning spirit with which one accepts the characteristics of nature. One does not complain about water because it is wet, or about rocks because they are hard, or about trees because they are green. As the child looks out upon the world with wide, uncritical, undemanding, innocent eyes, simply noting and observing what is the case, without either arguing the matter or demanding that it be otherwise, so does the self-actualizing person tend to look upon human nature in himself and others.

This is, as Maslow says, the stoic style, and one to which a person should aspire in a world where norms are flouted, wild things are done and wilder said, and perils real and imagined loom before us. Maslow’s healthy individual has little inclination to spluttering outrage, which does not mean ignoring unpleasant realities. Just the reverse, in fact.

Having settled into that frame of mind, what about the matter of predicting Trump-administration policies? Another even older friend, George Orwell, speaks to that one.

Political predictions are usually wrong. But even when one makes a correct one, to discover why one was right can be very illuminating. In general, one is only right when either wish or fear coincides with reality.

This, I suspect, is going to be a particular problem in dealing with the world of Donald Trump. Neither widely shared hopes (that he will ignore Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump Jr., for example, and be more or less normal in most respects) nor fears (that he’s going to do whatever he wants and be even crazier than he lets on) will be useful guides. But, being human, we will make judgments constantly distorted by both emotions. Orwell has a solution:

To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle. One thing that helps toward it is to keep a diary, or, at any rate, to keep some kind of record of one’s opinions about important events. Otherwise, when some particularly absurd belief is exploded by events, one may simply forget that one ever held it.

Useful advice from a man who confessed that most of his own predictions during World War II were wrong, although, as I know from experience, his remedy can be a painful corrective.

On what basis, then, should one attempt to predict Trumpian policy? A downright ancient friend comes to the rescue on this one:

Begin the morning by saying to thyself, I shall meet with the busybody, the ungrateful, arrogant, deceitful, envious, unsocial.

This, from Marcus Aurelius, the last good Roman emperor and a thoughtful Stoic philosopher, is not a bad beginning in looking at an administration that will have a few barbarians in it. He continues:

Whatever man you meet, say to yourself at once: ‘what are the principles this man entertains about human goods and ills?’ For if he has certain principles about pleasure and pain and the sources of these, about honour and dishonour, about death and life, it will not seem surprising or strange to me if he acts in certain ways.

So much of the contemporary speculation about the administration depends on the distinctive personality of the president-elect and some of his more outré advisers and confidantes. But simply ranting about them does not help one understand what is going on.

One of the troubles with the anti-Trump camp is the tendency simply to demonize. Some demonic characters may roam about the administration, but we would be better off trying to figure out what makes Trump tick. In particular, that phrase about honor and dishonor is worth pondering. For a man in his eighth decade with remarkable political success to his credit, who has just survived two assassination attempts, honor in Marcus Aurelius’s sense is probably something beyond “owning the libs.” More likely, Trump is looking to record enduring accomplishments, including a peace deal in Ukraine. Figuring out what he would like those to be, and in what way, is probably the best method of figuring out how to influence him, to the extent that anyone can.

Let us say that we get better at training our judgments and anticipating what the administration will do and why. There may still be plenty of things to brood about—the possibilities of tariff wars, betrayals of allies, mass deportations, attempts to prosecute deep-state denizens, and more. Even if Trump himself may be considerably less destructive than some fear, the MAGA movement will be out there: acolytes looking for opportunities to exit NATO, ban abortion entirely, make getting vaccines through Medicare impossible, sabotage the institutions that guarantee free and fair elections, or simply grift and corrupt their way through ambassadorships and other high government offices.

For that, something more spiritual is indicated, and I find it in the Library of America edition of one of the previous century’s deep thinkers, Reinhold Niebuhr.

God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.

Serenity will be something we will need in the years ahead. If you ask me, a well-stocked library will be of more help getting there than tranquilizers, wide-eyed staring at one’s mobile phone, or scrambling to find out if an Irish ancestor qualifies you for a European Union passport.