How the history of Op art offers a tangled reflection of the technological reality we face today

In 1965 the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (now Buffalo AKG Art Museum) opened the landmark exhibition Art Today: Kinetic and Op Art, and has since staged exhibitions such as The Eye’s Pop (1998) and Op Art Revisited (2008). Now, Electric Op repositions this movement in relation to current digital culture. Amid arguments over nature of the embodied human spectator versus the objective gaze of machine vision, the exhibition troubles these oppositions by exposing the systems that mediate how we see in the digital age.

Presenting over 90 works spanning six decades, the exhibition opens with the perceptual impact of Op art: the moiré effect (when overlapping lines create interference patterns that make a work seem to tremble) is mobilised by Yaacov Agam’s three-dimensional Free Standing Painting (1971), whose alternating, brightly coloured vertical slats create an effect that feels like a cross between a Mondrian painting and a game of Tetris. As audiences walk around it, it establishes the role of the body in perception. Martha Boto’s wall sculpture Interférences Optiques (Optical Interferences) (1965) broadens this effect to kinetic and electric media: points of light seem to move within a four-by-four array of loosely shuttered cylinders inserted into a black wooden square, as if riffing on vintage camera boxes and lenses.

Elsewhere, Op art’s flair for manipulating depth perception is highlighted in works by artists ranging from computer-art pioneer Georg Nees and kinetic art trailblazer Carlos Cruz-Diez to colour theorist Josef Albers, represented here by an engraving on black laminated plastic of an unfolding origamilike structure (Structural Constellation F.M.E. #3, 1962). Al Held’s canvas Piero’s Piazza (1982) startles with a lurid, neon green upright grid moving through a fever-dream space of colour-clashing hoops, grids and cuboids, which nevertheless pays homage to Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca’s use of single-point perspective.

Many works suggest genealogical affinities between Op art and contemporary digital art. Casey Reas’s METASOTO (2022) responds to Jesús Rafael Soto’s Bois-tiges de Fer (1964) on an adjacent wall. Soto’s work, a rectangular piece of painted Masonite, has been inserted with metal rods from which hang translucent nylon threads that barely move and cast faint shadows, glimpsed as the viewer moves past the work. Though a computer screen might not seem endowed with a similar visual subtlety, Reas’s work shows how an algorithm can produce delicate distinctions in simple white lines against a black background, discovered as visitors use a mouse to click through its permutations.

If Pop art recognised the media image as our new ‘nature’ and Minimalism was an art of phenomenological sensibility, Electric Op proposes perception as an artifact of relations among biological, material, technological and intellectual systems. More challenging yet are our relations with that which we cannot see, or don’t yet know how to see. A wall installation presents Rosa Menkman’s strange web-based work The BLOB of Im/Possible Images (2021). She invited physicists and others to posit an image that cannot actually exist, which she then generated as various abstractions, located within a black and white immersive online space that is unexpectedly entrancing. Popup windows provide some sense of what prompted the particular abstractions, but the project emphasises the challenges of visualising conceivable but unavailable phenomena as we reconcile ourselves with advances in contemporary physics and computer science.

Electric Op suggests we recognise patterns of interference in the material as well as social conditions of bodies, software and hardware. Laura Splan’s Squint (2016) is a greyscale Jacquard-loom tapestry of abstract wave forms that are based on her own facial expressions, recorded via facial electrodes. The data appeared as wave patterns that she then used as the basis for her weaving process. The loom’s historic relevance to computing gets woven into a narrative of developments linking body and technology.

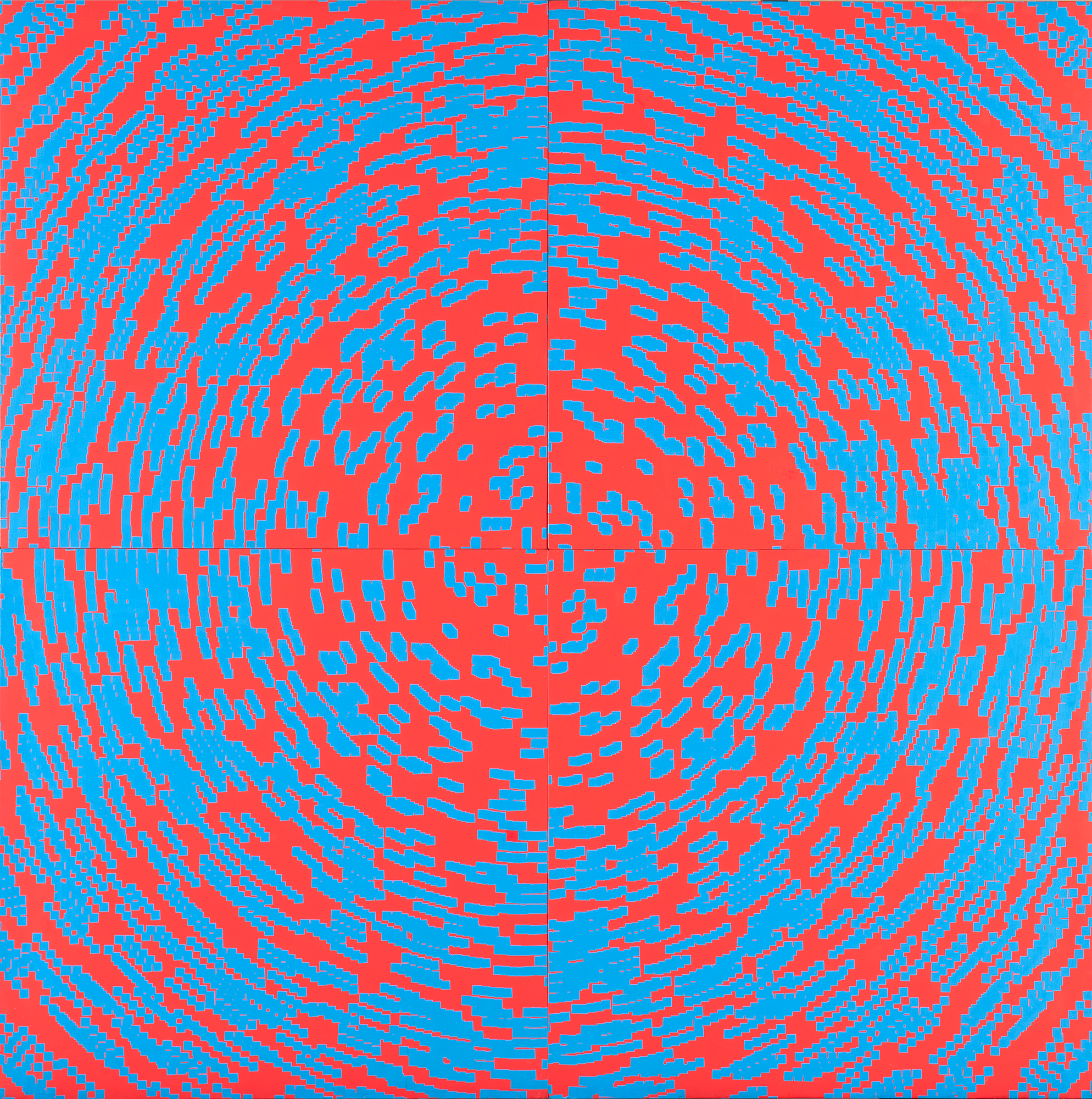

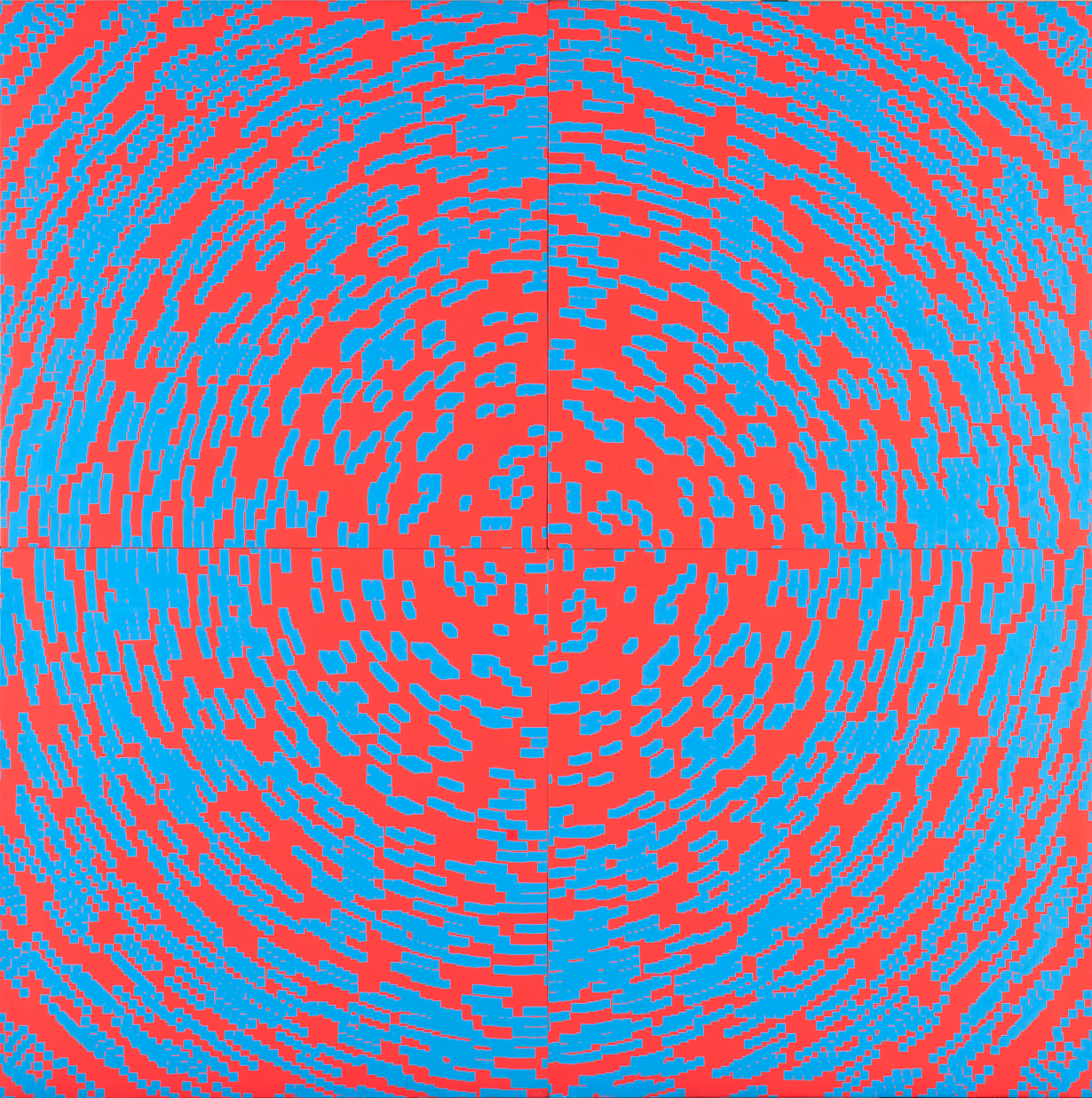

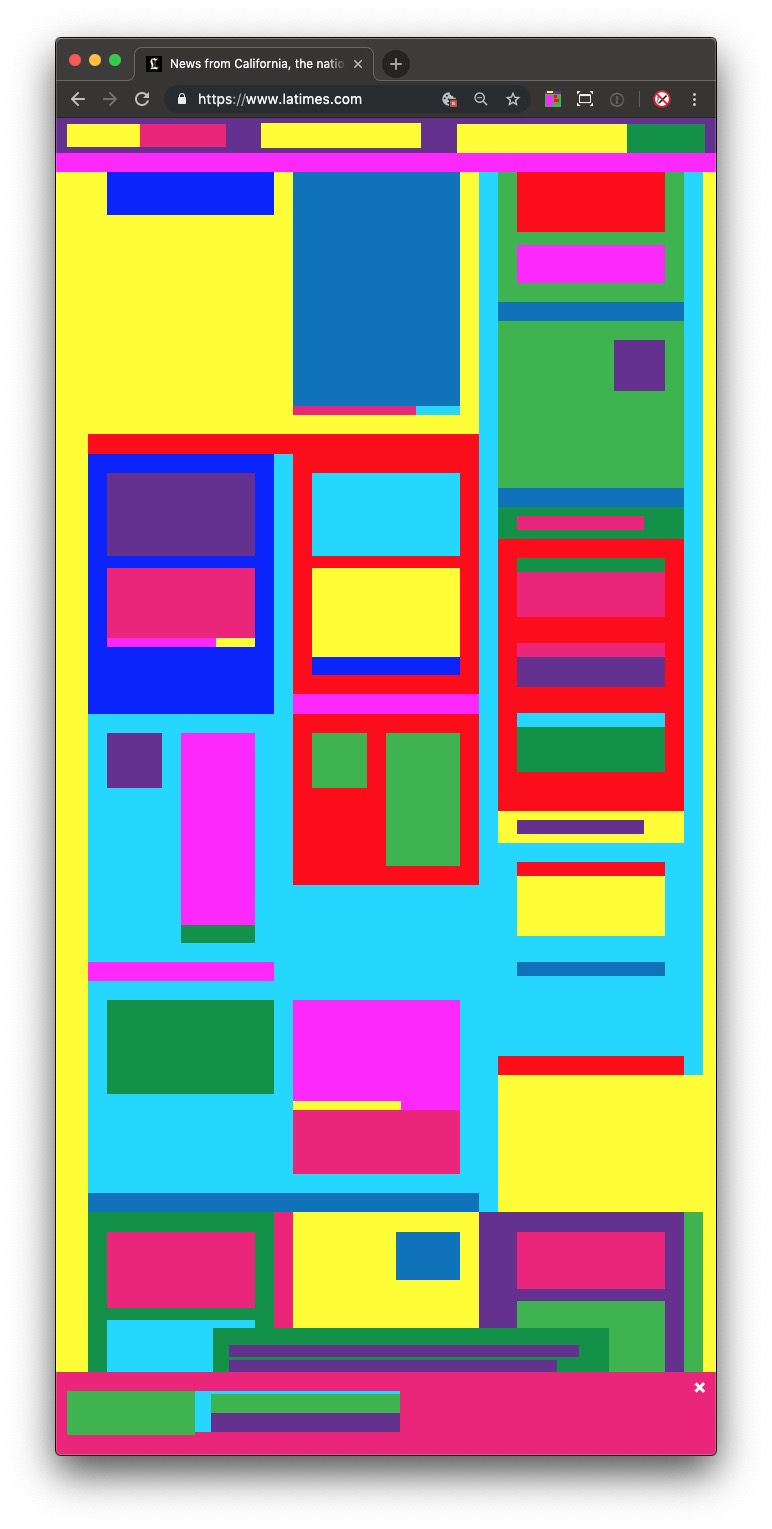

Software quite literally programmes how we see. Rafaël Rozendaal’s net art project Abstract Browsing (2014) here presented on a large screen, where audiences can observe a scroll of vivid rectangular forms. The result of Rozendaal’s web browser plug-in, free for anyone to download, it represents the effect of losing all text and symbols in a website and reveals that the loss of text doesn’t impact a user’s recognition or navigation of the website, reinforcing the importance of design. Jason Salavon’s real-time animation Everything, All At Once (Part III) (2005) is a technical feat: local live broadcast television, shown on a monitor in the corner of the room, is also processed through Salavon’s own software, the colour palette and sounds of the TV image coded into concentric coloured rings that shift in hue and distribution as they are projected on the gallery wall.

The performativity of such works, reactivating our generally pacified interactions with media, calls for an awareness of the myriad forces that impact how we see, think and move. Electric Op presents a genealogy for digital art distinct from the art, design or new-media lineages that are now well established. The show’s cybernetic phenomenology challenges a Newtonian cause-and-effect worldview, proposing a more complex system of relations and perspectives increasingly relevant to the tangled ecological, political and technological situations we face globally.

Electric Op at Buffalo AKG Art Museum, through 27 January

From the November 2024 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.