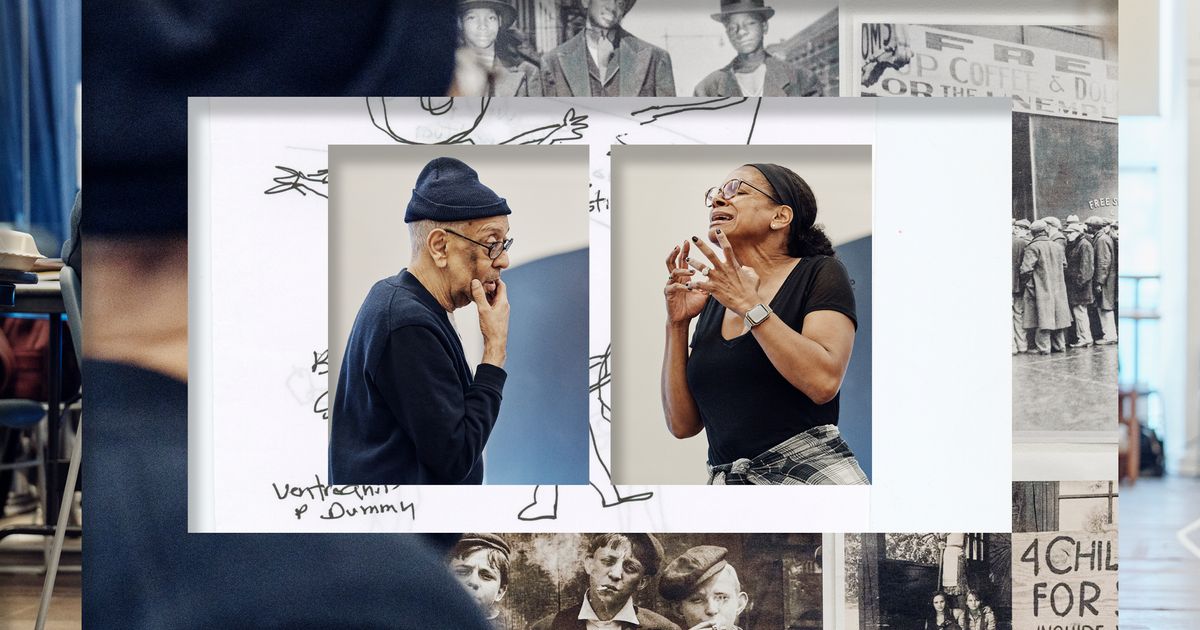

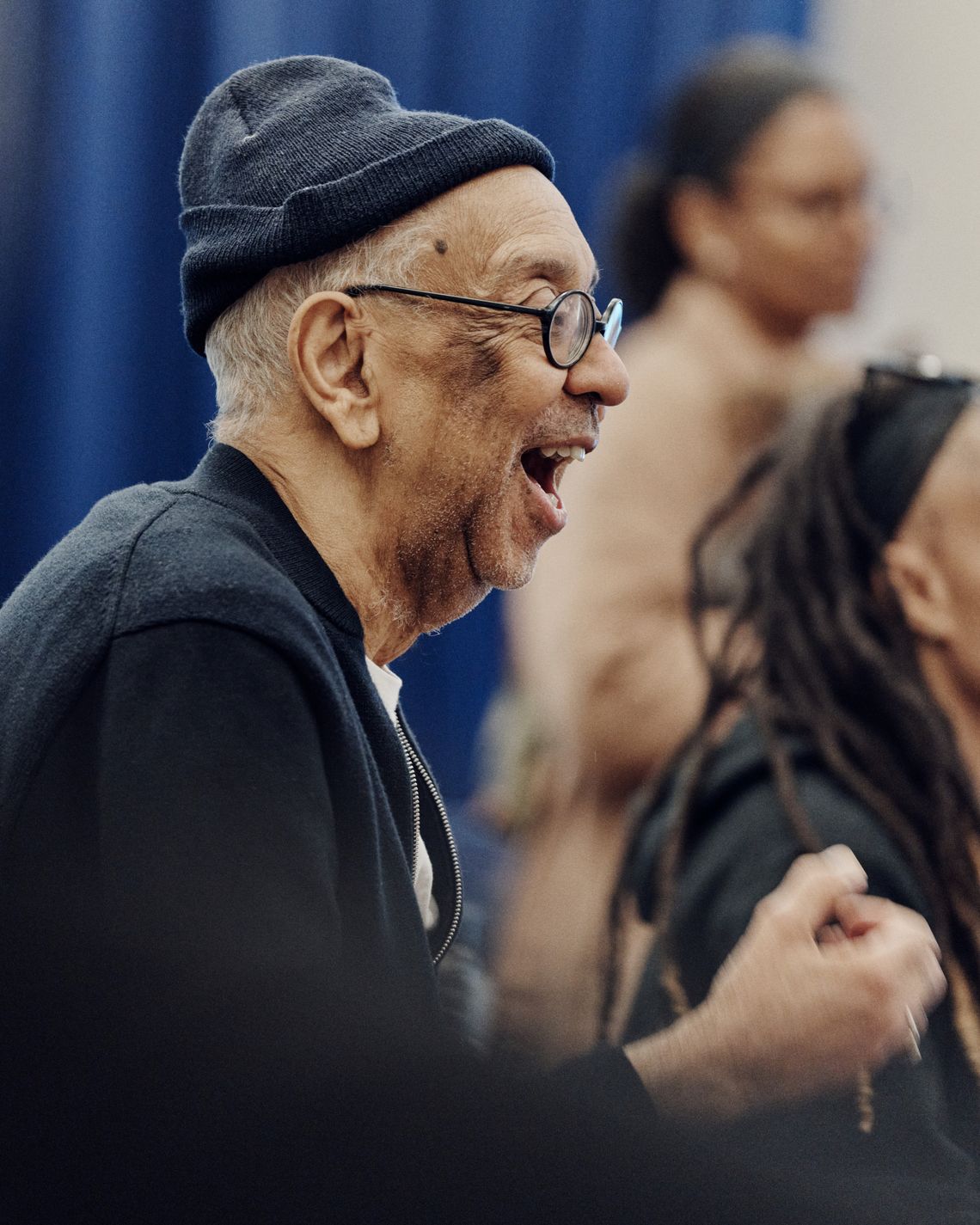

Director George C. Wolfe and Audra McDonald in rehearsal.

Photo-Illustration: New York Magazine; Photos Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

Audra McDonald was standing to my left in a long coat and leggings, a narcoleptic lapdog in her arms, but I didn’t notice. There’s nothing diva-y about her; nobody even glanced in her direction. It was 50 days before the opening of Gypsy, starring McDonald as the devouring stage mother Rose, and there was a lot to do. George C. Wolfe, the director, restless and elfin in a beanie and slipper shoes, sat on a chair in the 42nd Street rehearsal room, watching the busload of children in Gypsy, giggling and poking one another, come in from the hallway.

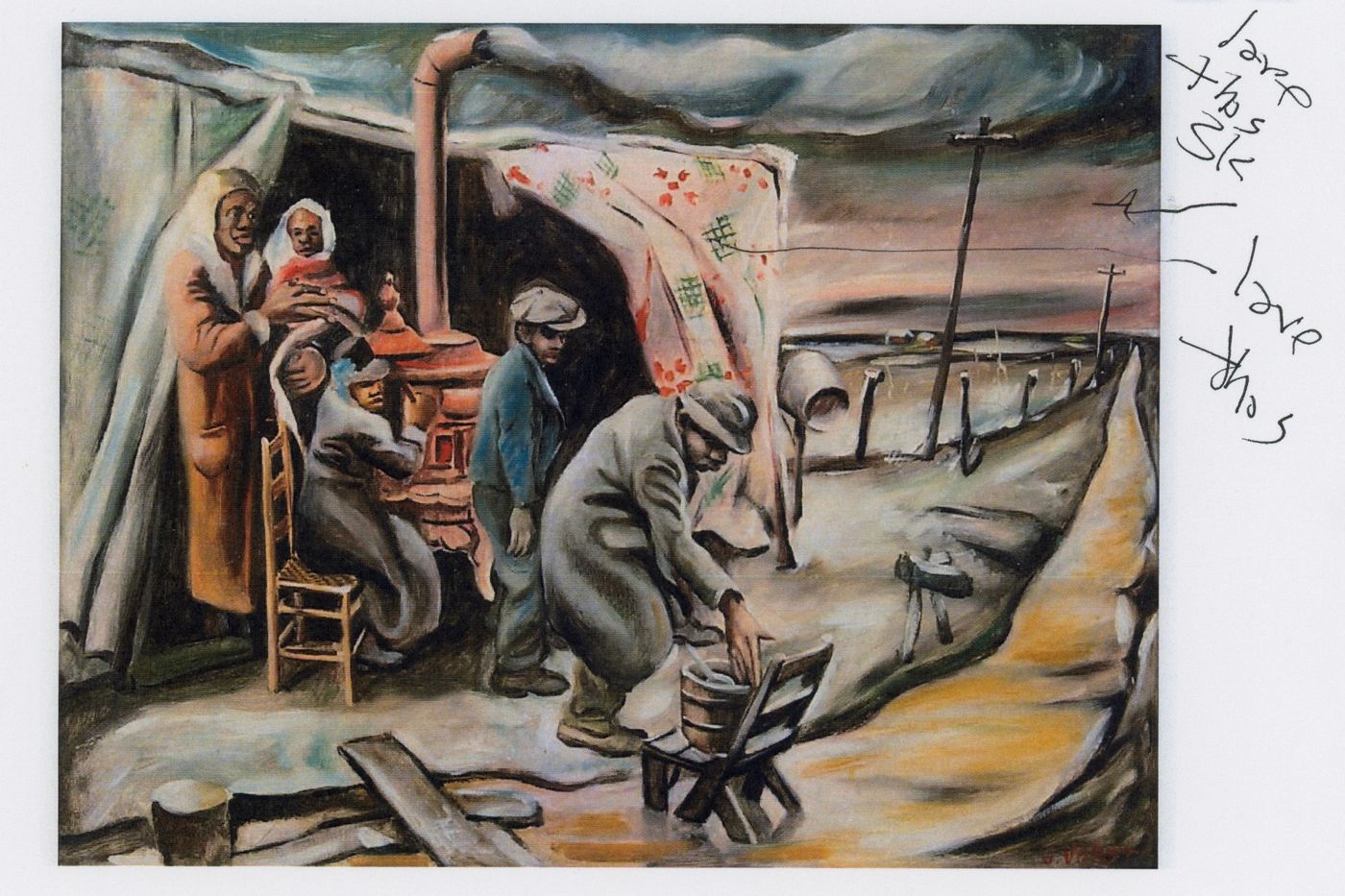

On the wall was a kind of mood board of pictures from the Depression, when the show is set.

Photo: Courtesy of George C. Wolfe (painting); Bettmann Archive/Getty Images.

Photo: Courtesy of George C. Wolfe (painting); Bettmann Archive/Getty Images.

Every inch of the space was alive with activity: the actor playing Tulsa stretching alongside other dancers in the room next door; the three strippers from “You Gotta Get a Gimmick,” the showstopping Act Two number, rehearsing their moves on the sidelines with the choreographer, Camille A. Brown, while the music director futzed with some orchestration in the corner. Eventually, the run-through began, playing out in ordinary fashion if you’ve seen the show as often as I have in its many iterations. We were watching the first ten minutes, in which Rose and her daughters are introduced at an audition for a kiddie vaudeville show. Rose is trying to foist Baby June and Louise on the host, which leads to a confrontation with Rose’s father over the life she has forced on her children, culminating in Rose’s first big anthem, “Some People.” Wolfe sat on the floor, then leaped up; he was in constant motion. He worked out some blocking and exchanged a whispered word with McDonald. He talked to the actor playing Rose’s father about what he might be feeling in the scene, which caused the actor to ratchet up his line-reading several notches. But it was all a familiar rendition of a musical that’s been revived five times since it premiered nearly 66 years ago.

Jade Smith as Baby June (top), Audra McDonald as Momma Rose (top and bottom), and Thomas Silcott as Pop (bottom), rehearsing the opening scenes. Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine.

Jade Smith as Baby June (top), Audra McDonald as Momma Rose (top and bottom), and Thomas Silcott as Pop (bottom), rehearsing the opening scenes. Photo…

Jade Smith as Baby June (top), Audra McDonald as Momma Rose (top and bottom), and Thomas Silcott as Pop (bottom), rehearsing the opening scenes. Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine.

Two words sit on the marquee of the Majestic Theatre: AUDRA GYPSY. Audra McDonald is a once-in-forever talent. A truly excellent actress who also happens to have an otherworldly instrument, she has an unusual voice for Broadway: a tremulous, almost-operatic soprano with exquisite phrasing that reminds you just how intelligent a singer she is. Listening to McDonald sing (especially in a rehearsal room, where I was surprised to hear she holds nothing back) is, for a theater-crazed person like myself, a religious experience.

Still, McDonald, winner of six Tony Awards, is not, in a sense, a natural for the part of Rose, a role usually played by a star riding her larger-than-life charisma and blistering belt to a standing ovation. To those unfamiliar with the show (is there anybody?), Rose is Lear, or Medea, if you’d like. She is a gargoyle of a stage mother, desperate to push her children into a spotlight she’d always wanted for herself. Eventually, exhausted by their mother’s brutal efforts to make them vaudeville stars, they each strike off on their own, leaving her alone. June escapes to make her own way as an actress; her sister, Louise, parlays her lack of talent into becoming the world-famous stripper Gypsy Rose Lee. The show is loosely based on the stripper’s memoir, but Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book, refashioned it as the story of her mother. In his account, he met a woman who claimed to be Rose’s lover, heard tales of her stubborn treachery (and charm), and knew he could write a show any musical actress would kill to star in. Gypsy opened in 1959. Since Gypsy first opened, Rose has been played by Ethel Merman, Angela Lansbury, Bernadette Peters, Tyne Daly, Imelda Staunton, Rosalind Russell (in the movie version), and Patti LuPone. With each Rose came a new interpretation, but pretty much every Rose is a big brassy bully with a big brassy voice.

Several years ago, at the urging of the actor Gavin Creel (who also had urged McDonald to do the part), McDonald approached Wolfe and asked if he was interested in directing her in Gypsy. They had worked together before on the show Shuffle Along and later the movie Rustin. McDonald was comfortable with Wolfe. But anybody would have thought him a dream director for the project. He has lately been a film director (in addition to the 2023 Rustin, he also directed Lackawanna Blues and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), but for most of his career he was a theater colossus, winner of five Tony Awards himself. He’s the writer of The Colored Museum and the director of the musicals Jelly’s Last Jam (which he also wrote), Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk, and Caroline, or Change; of contemporary plays like Angels in America and Topdog/Underdog; and of classics like The Iceman Cometh — the list goes on. For a time, he ran the Public Theater; in 2024, he got a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Tonys.

So Audra McDonald was the star and George C. Wolfe was the director, a pairing that made a certain breed of theater fan delirious. But what does a director do? I admire theater directors (and, when I was a kid, wanted to be one) but have always been fuzzy on the job description. Broadly speaking, they are the boss — it is their job to have a vision for the thing and then to realize it. Because they are in control of what you see, and since generally what the audience can see is stagecraft — striking ways of moving actors across stage — they are often praised for movement or memorable tableaux. I personally get a big thrill from a director controlling the way my eyes move across a stage. Jerome Robbins, who directed the original Gypsy, invented a dazzling way to age his performers in a single dance number, where a strobe prevents you from seeing the younger actors giving way to their older counterparts. One theater friend I know described this as the most impressive coup de théâtre he has ever seen, and I know what he means. We’ll get back to that in the spoiler section.

But revivals are a particular matter. For revivals, directors often want to reinterpret the work or stage it in a way that shows off their talents — directors can have as much vanity as actors. There are directors like Ivo van Hove, whose imprint (in his case, the integration of video into live performance) is so vivid that, for better or worse, they become the star. John Doyle restaged various Stephen Sondheim shows, for which he miniaturized the productions and gave the actors instruments to play. As Brown said to me, “I think the challenge with a revival is, because there have been so many iterations before, Why now? Why are we bringing this forward?” That was my question too. In some respects, McDonald as Rose was reason enough to revive it (certainly for commercial purposes). But Wolfe was one of theater’s great directors directing one of theater’s great musicals — I was sure he’d have something more ambitious in mind. Still, I hadn’t seen much “new” at the rehearsal he invited me to. There was no apparent imposition of his ego on the production.

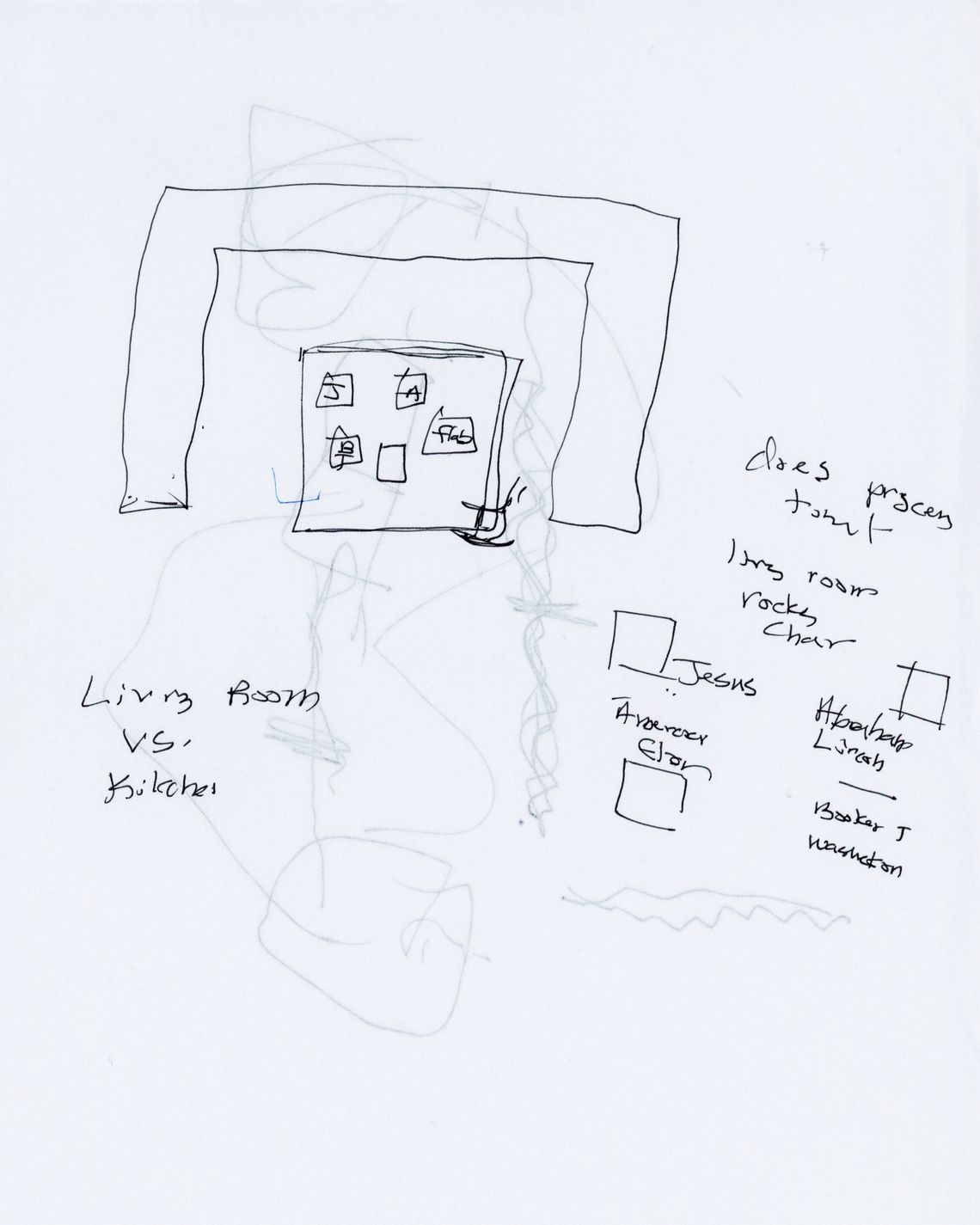

Wolfe signed on to the job last winter. He cast the show and started talking with Santo Loquasto, the set designer, in the summer (imagining the space is the first step) …

Photo: Courtesy of George C. Wolfe

He began discussions with Brown …

Photo: Courtesy of George C. Wolfe

… and his costume designer, Toni-Leslie James.

They had their first table read very late in September, and they would open on December 19 — a remarkably short-seeming spurt for a production this big.

But I wondered what Wolfe was bringing to these conversations. I’d passed by a dramatically overhauled Sunset Boulevard across the street on my way to the Majestic, so I had grand gestures in mind. As we sat down on the couches in the theater’s basement, I pressed him for something conspicuous, some visible reframing, but he waved that notion away.

He launched into a story about Elaine Stritch, whom he directed in Elaine Stritch: At Liberty. When he started to think about Gypsy, he said, “one of the first images that came into my head was when Elaine moved from the Newman [a small theater at the Public] to the Neil Simon [a much bigger one on Broadway]. It was our first day in the new theater, and Elaine was pacing across the stage.” He got up to imitate Stretch, hilariously; she was one of the theater’s great eccentrics. “And she said, ‘This is bigger than the Newman?’ I went ‘yes.’ She said, ‘I like it!’ And then my next thought was that this piece” — this Gypsy he was about to direct — “is about there never being enough: never enough love, never enough space, never enough money, never enough attention. It’s filled with characters who never got enough. Finally, at the Neil Simon, Elaine got enough. And that put me on the journey of someone wanting more and never getting it.”

What Wolfe did, he told me, was scour the script. He parsed every line, every speech, every lyric. He saturated himself in the Depression, which he thought might have more to do with Gypsy than others had worked with, and had long conversations with McDonald. “I go digging,” he said. “I learn about the period. I go digging for images, and it all opens up things inside my brain.” Wolfe started isolating moments in the book and score as clues. “Sometimes a single word is enough to open a door,” he said. In the scene I’d witnessed in the rehearsal, Rose is eating dog food, which is often played as a joke. It was funny here, too, but Wolfe also took it more seriously. “It’s a joke, but that’s dog food. She’s hungry,” he explained. “What more needs to be said?” He sounded more like a literary critic than what I imagined a director to be.

We talked about the scene I’d seen a couple of weeks before and McDonald’s singing of “Some People.” Typically, it’s played as the big star’s go-get-’em song that explains her ruthless determination and launches the action, but he was particularly fixated on the multiple meanings of the word dream. “Rose sings ‘It’s a wonderful dream, Papa’,” said Wolfe. “She’s obsessed with this dream, and she’s trying to convince a man who doesn’t believe in her of a possibility she sees. It’s part hustle. But she’s also sharing something, and when he steps on it, she says ‘Fuck you’ to him.”

“I became fascinated by this woman,” he continued. “ ‘Someone tell me,’ she sings, ‘when is it my turn?’ I became obsessed with that line. So she set out, and there was no blueprint, no road map. Not enough. The path that was designed for her was uninteresting to her. I understood that very personally. I had a grandmother who was my protector who was also very ferocious. I saw my mother stop being a mother so she could go back in her 50s to get a doctorate. I grew up around these women who just went ‘no.’ ”

Through his digging, Wolfe came to a reading of Rose that I had never considered. At a couple of points in the script, there is a mention of her being abandoned by her own mother — which was true of the real Rose (even though much of Gypsy is made up). “Rose’s Turn” is the emotional climax of the show, the crack-up moment when she confronts her own awfulness and her abandonment by all the people she loves. In the song, Sondheim, who wrote the lyric, has her stammer the word Momma. To Wolfe, this was the key to the whole show. “The phantom mother who abandoned her when she was young is so huge,” Wolfe said. “In ‘Rose’s Turn’ ” — he told McDonald — “if she’d never said the word Momma, she could have made it through the song without falling apart.”

Laurents famously asked Merman if she was prepared to play Rose as a “monster.” Wolfe had earlier mentioned one small change he’d made in the show. In the original Gypsy, when Rose takes her children on the road to start their vaudeville climb, she kidnaps a group of boys to be in the act, but, in his version, Wolfe has her rescue them instead, a change to make her more palatable (also kidnapping wasn’t exactly a good look). “I’ve talked about that with Audra a lot,” Wolfe said. “Is she a monster, or is she a monster because she says, ‘I’m not doing what I’m supposed to do’?” I was beginning to see what Wolfe was after — Wolfe’s Rose might do monstrous things, but she was maybe less an ogre than a victim herself. Other Roses had certainly tried to find the humanity in her, but how Wolfe (and McDonald) negotiated Rose’s monstrousness might alone make this a different Gypsy.

Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

Wolfe watches Lesli Margherita, who plays Tessie Tura, rehearse.

Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

Of course, if I was looking for a different Gypsy, it was hard to ignore the obvious: In this production, Rose and her children are Black (or mixed race). Was I supposed to ignore that? I’d gotten the impression that Wolfe intended the production to be color-blind, but I wasn’t sure. I’d remembered reading, in a column by John McWhorter, that “for Rose to think her [Black] kids had even a chance at becoming America’s sweethearts … would be a delusion so quixotic that it would have to be the story’s central tragedy” — just not quite possible, historically. When I brought up the role he wanted race to play in this show, I was surprised that he reacted as if no one had ever asked him that (I realize that was a little disingenuous on his part): “That’s an interesting question. I don’t know because we’re still exploring. We’re perpetually looking at racial dynamics, not as a treatise of what it was like, but how does it manifest itself in the character’s perception of herself?”

Upstairs at the Majestic, I saw this exploration during a day of tech rehearsal. They were replaying a scene over and over — the one in which Mr. Grantziger, a Ziegfeld-like impresario, offers to take June away from Rose and make her a star. Rose goes ballistic. Wolfe kept reblocking the scene: He sat in the orchestra but kept advancing to the stage, moving the actors and lying there like a cat, curling up so he himself was unimposing.

“There are two primary schools of directing,” Wolfe told me. “One where you stand where you are and demand that actors come to you, the other where you go where they are and you engage your charm, seduce them to go on a journey till they end up in the place that you think they ought to be. You ingest their perceptions, they ingest yours, and it becomes an amalgam.”

During the tech rehearsal, he kept interrogating the actors (McDonald especially) about the stakes of the meeting in Grantziger’s office. Wolfe said, “She finds herself in a room where there are people with a lot of power and a lot of money, and she has neither. How much is she aware of the power structure? What’s going to happen once this man takes possession of this pretty little girl?”

To my surprise, he brought up her race: “I mean, also, she’s the mother of a little Black girl. Her little baby girl is going to be entrusted in the care of some rich white man.” So, not color-blind at all. But also not literal-historical. Instead, race figured as something more internal, as aspects of a character. He was having it both ways, but I got it: When you consider Rose’s motives charged with a racial dynamic, a lot changes.

“I remember some event at the Dramatists Guild, and I came home and wrote a poem,” Wolfe said. “He was the only spot in the spotless room. And he got through the door without pushing a broom. Sometimes I’m George the director. Sometimes I’m George from Kentucky. Sometimes I’m gay George. And sometimes I’m Black and the only one there. All those dynamics, the dynamics of a woman who is abandoned by her mother, just like different versions of myself, show up at different times depending on the circumstances.”

So race would be a factor, but not the only one, and he made sure every actor understood how their motivation at any minute might affect their characters. At one point, he went over to June, who was not landing a crucial joke, and whispered comments to her. Then she got the laugh. Later, when I asked him what he’d said, he couldn’t remember but told me, “I work very, very hard never to tell an actor ‘no.’ You don’t violate what they’re bringing because they’ll shut down and it’ll be really hell. Because when you tell them ‘no,’ it kills the impulse in them to explore and try. At one point in rehearsals for Angels in America, I said to Ron Leibman [who played Roy Cohn], ‘When you do this, the audience says Ron Leibman is a brilliant actor. But when you do that, the audience says Roy Cohn is a scary man. Which one do you want?’ ”

He was much more psychologist than technician — or autocrat. Mainly, he was just talking to the actors over and over about what the small scene was about and letting them figure out what to do about it.

A couple of weeks later, it was time for the first preview. Wolfe considers the previews as important a part in the rehearsal process as any of the phases before it because it’s the first opportunity to see how the show connects, or doesn’t, with the audience. “We’re not the victims of the audience. They’re our victims and they’re going to help us. Our final scene partner has showed up and it’s them.”

I was eager to see the show as a whole, but even after listening to him and watching rehearsals, I still had doubts about what all this would add up to. Orienting a version of Gypsy around “I had a dream” and “When is it my turn?” — these are the most famous lyrics in the show — did Wolfe really have something new to say? In other words, would his burrowing be enough? I kept asking him to be specific about what he’d done to breathe his vision of Gypsy into his actors. All he really seemed to be saying is that he talked to them. How much difference could that possibly make?

Photo: Thomas Prior for New York Magazine

I am not a critic, so I’ll be careful here to only speak from my own experience of it, but the answer for me came decisively, a rebuke to what I came to understand as my naïveté about what directing was really about: Yes, it made a difference, and absolutely, it was enough. In subtle but crucial ways, it was a distinct and more powerful Gypsy than I had ever seen before.

The physical production did not dramatically deviate from the Gypsys that came before it. Every line was the same; also many of the shticks. The overture was as exuberant as ever. As in every other production I’ve seen, Rose makes her entrance from the back of the theater. When McDonald appears, the audience does what it is expected to do: erupts. In most respects, Wolfe could have stopped there. He gave the audience what it had come for.

McDonald’s voice was glorious, but some theatergoers were bound to resist it because it sounded so different from the star turns on all the cast albums. You could feel that resistance in the room; you could also feel it dissolve after a few minutes because McDonald’s richer, more modulated vocal instrument, though not conventional for musical theater, enhances a score as strong as this one. It wouldn’t work as well with music that is belted to disguise the fact that it isn’t very good, which is usually the case.

But the stagecraft and the perfect score appeared secondary. Not everything worked for me, but the important stuff did. The racial shift mattered in ways that didn’t announce themselves but were palpable. I’m still not sure how Wolfe did it (Joy Woods, who plays the older Louise, told me that Wolfe directs by telling stories, the lessons of which the actors absorb into their role-playing — sort of, it seemed, the way Yoda worked), but all his careful reading of the text and interrogation, the unflashy ways he moved the actors across the stage, shifted the show into one deeply rooted in hunger and, even more than that, hurt. McDonald plays her as a tragic heroine terrified of abandonment. The result is a Rose for whom I felt more sympathy than seems possible. The quieter numbers — “Together Wherever We Go,” “Small World,” “You’ll Never Get Away From Me” — were especially revelatory. And it wasn’t just McDonald. “If Momma Was Married,” sung by June and Louise, and usually just a lovely song, seemed to me now the dramatic center of the show. That’s because June plays it with raw pain, after she has, as Woods’s Louise told me, freed Louise from “the cult that her mother has built their lives around” — making you feel the consequences of Rose’s narcissism, while at the same time allowing you to forgive her for it because her own victims do. Rose is a ferociously selfish parent, but she also loves her children with an intensity she herself had been deprived of as a child. I saw that in a way I had never before. When you get to “Rose’s Turn,” it is devastating — and not because she is a monster but because she is a wound.

So what happened? I had been looking for something I could see, but maybe the art of direction is what you can’t see. This much I knew: Wolfe was meticulous. He had thought through every single moment in the text. He made no decision because it would look cool or have an extraneous theatrical effect. “You figure it out,” he said to me. “The world has entered you, then you invite other people to enter the world you create.” His principal tool is conversation. The rest is kind of like osmosis. “The ultimate job of a director is to make yourself invisible. So it looks like those words, those choices, are being made up in the moment,” Wolfe said.

One particular image he found online, an archival photograph of a mother advertising her children for sale, guided his thinking throughout. It is ghastly.

Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

“I instantly understood,” he said. “She’s not a horrible mother. She can’t feed these kids. Not enough food, not enough success, not enough money. It’s all there in the book.”

And while I had wondered before I’d seen it whether Wolfe had missed an opportunity to update a 66-year-old musical, in fact, he kind of did. All that mystical manipulation had turned Gypsy into a show about trauma and how one deals with it, which is a very modern thing to be about.

“The other day I said to the company, ‘If you have any conversation about money, it’s blood, A blood fight.’ Negotiating about a dress, negotiating salary, anytime money is mentioned in a scene, it’s not a casual reference; it’s life or death. And just infuse that in your body and then the audience will absorb the stakes of what’s going on. That ferocity, which is fueled by fear, which is fueled by desperation and the joy — I make sure that is behind the performances as much as possible and as much as the material will allow. I keep asking them, ‘Who has the power, who has the power in this fucking scene?’ That changes an actor. There’s no such thing as a neutral choice.”

“The first thing is to build a structure where they feel safe enough to expose their frail hearts. A lot of the rehearsal process is digging and asking the question, ‘What’s underneath the thought?’ I find actors to be incredibly brave people. And I try to create as protective an environment as I possibly can.”

“A Croatian director named Georgij Paro gave this lecture that was close to an owner’s manual of directing. He said that a director acts in front of the actor, shows them the effect of the actors acting — which is what an audience does, too. You are perpetually offering up yourself as a perspective so they are in essence cultivating their own director while being an actor inside of the role.”

“It’s all about rhythm. I went to a Knicks game once, and I thought, Oh, this is rhythm, every minute of it, from the beginning to the end. I said, ‘I want to make a show like that.’ And that’s where Bring in ’da Noise came from: I wanted to control the audience for the entire time.”

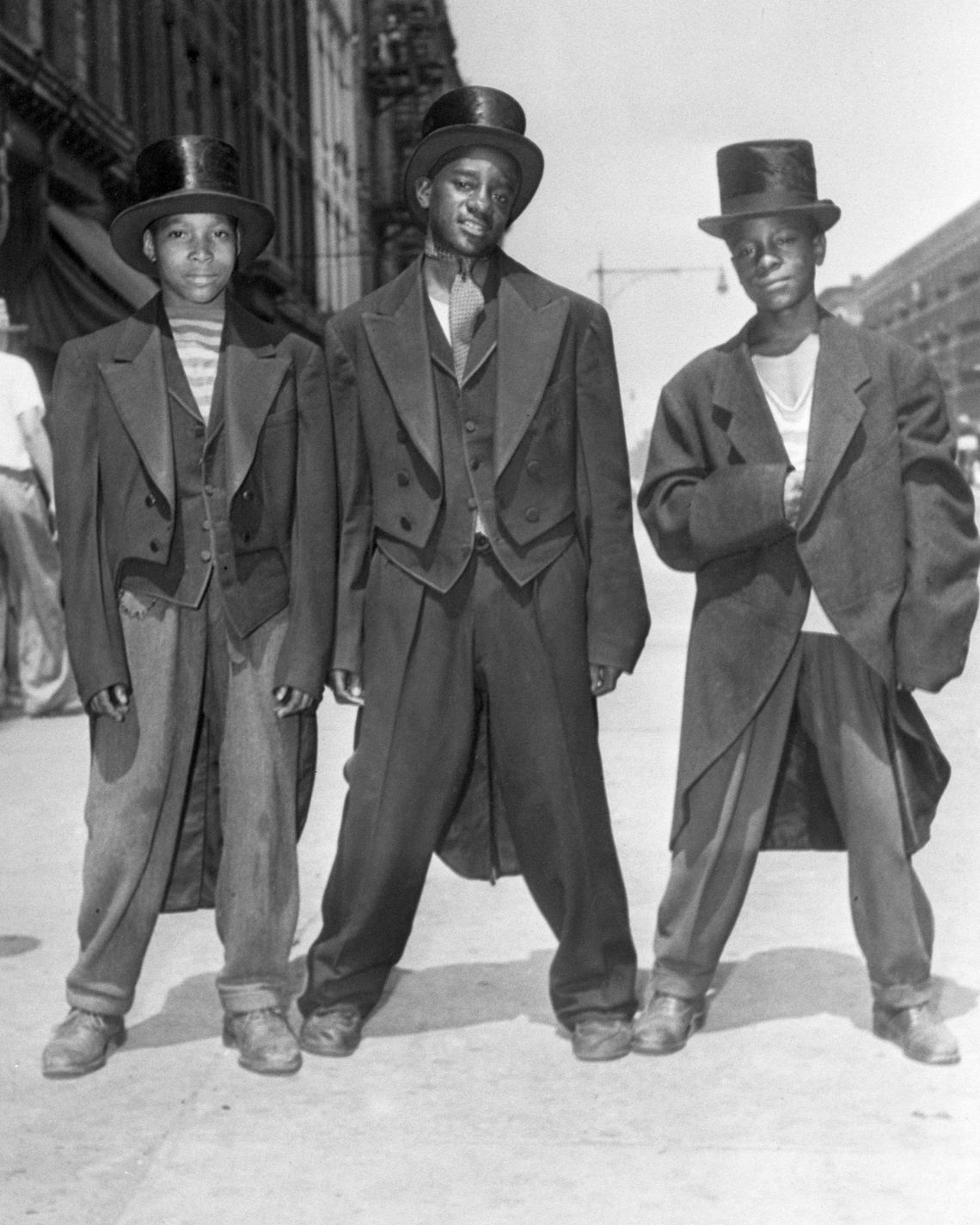

“Early on, I knew I wanted to start with little Black boys and then end up with young white boys,” Wolfe said. “I didn’t want to create a sense of wonder, which is what the strobe does. I wanted to invite them into her decision-making process. She’s determined that her kids, her Black daughters of varying shades, are going to be stars, going to do the Orpheum Circuit, going to Broadway. They’re going to be powerful and beyond harm. Beyond racism. She knows what America is, she knows what it means to be a person of color.” So Rose gets white boys to help make the act successful. “There are plays that examine this in a very specific way. I’m using it as an energy,” he said.

“To me, it was interesting about assimilation, following historical legacies about showbiz and entertainment,” Wolfe said. “I’m not telling the Lena Horne story. But June becomes the archetype of the day, which is also what Rose did to June Havoc, with all that Shirley Temple cutesy-pie Americana. She’s selling America. “

“Well, she’s styled as many things. There are many things I was playing with,” Wolfe said, “such as serving people up as an object. That was not Rose’s intention, but that was what ended up happening. If women can’t exist within the structure that has been decided for them, that’s one of the options. When Louise is taking pictures for the French photographer, there’s an incredible line that goes, ‘Show us your talent.’ And last night I just had her pulling back her dress and showing her leg. I wanted it to be this intense sort of subtext that was infusing the action. It’s telling these stories that are American stories. I became fascinated with the composition of the creative team. Sondheim was part of the Sondheim-Prince legacy, where a darker edge began to infiltrate musicals. And Jule Styne [who wrote the music] was of another tradition. I felt like this show was what it was on the way to what it would become.”

“Yeah. You just switch things out,” he said. Race informs her motivation but isn’t necessary. “Her decisions are rooted in wanting more, of desperation.”

Adam Moss: I noticed in this production, you allow the kids to end “Some People,” which is usually her song —

George C. Wolfe: With “but not Rose,” because she’s just given them food, so she’s a hero in their eyes —

A.M.: And share “Have an Egg Roll, Mr. Goldstone” with Rose — normally it’s entirely her song.

G.C.W.: They all want to be performers, they have no options, she’s paying them nothing, and all of a sudden there’s a man who comes into the room who can change their lives. There’s a collective desperation.

A.M.: I’d wondered if there was some effort on your part to make this less of a star vehicle than it had been written as.

G.C.W.: You feel this as less of a star vehicle?

A.M.: In a sense but in good ways. This show is still about her, but it’s not a belting show anymore. And Audra seems a more generous and modest performer than her predecessors.

G.C.W.: Well, that was not in any way the intent. What fascinated me about the book is how everybody is part of this drive that this woman had.

A.M.: Rose is a director. Do you relate to her?

[Wolfe laughs at the thought.]

A.M.: Was there a part of you that wanted to be in front, as Rose does?

G.C.W.: [Laughs again] I was an actor in college, but I have control issues.

A.M.: It’s a matter of temperament, isn’t it? I’m an editor mostly. And I find most editors are control freaks at heart.

G.C.W.: There’s a [set designer] Robin Wagner quote I love, where he said, “Collaboration is a word that directors invented to make everybody feel good about obeying them.” When I acted, I knew the correct rhythm and I would use my acting to manipulate the person I was acting with so they would do it correctly. I went, That’s not how an actor thinks, George. Everything was leading me in the direction of direction.

Ben Brantley recently broke it down in the Times.

“You start with these images and then you journey into something more abstract,” Wolfe said. “It’s like Pop’s house is normally set in a kitchen. And I set it as if it were a flat in a Broadway show. I wanted it to feel like an ethnic-kitchen-scene drama. I said, ‘Let’s make it like a flat in an old kitchen scene.’” Every detail was observed. “What would be on the wall? Jesus. Abraham Lincoln. And given the time period, Booker T. Washington, definitely not W.E.B. Du Bois.”

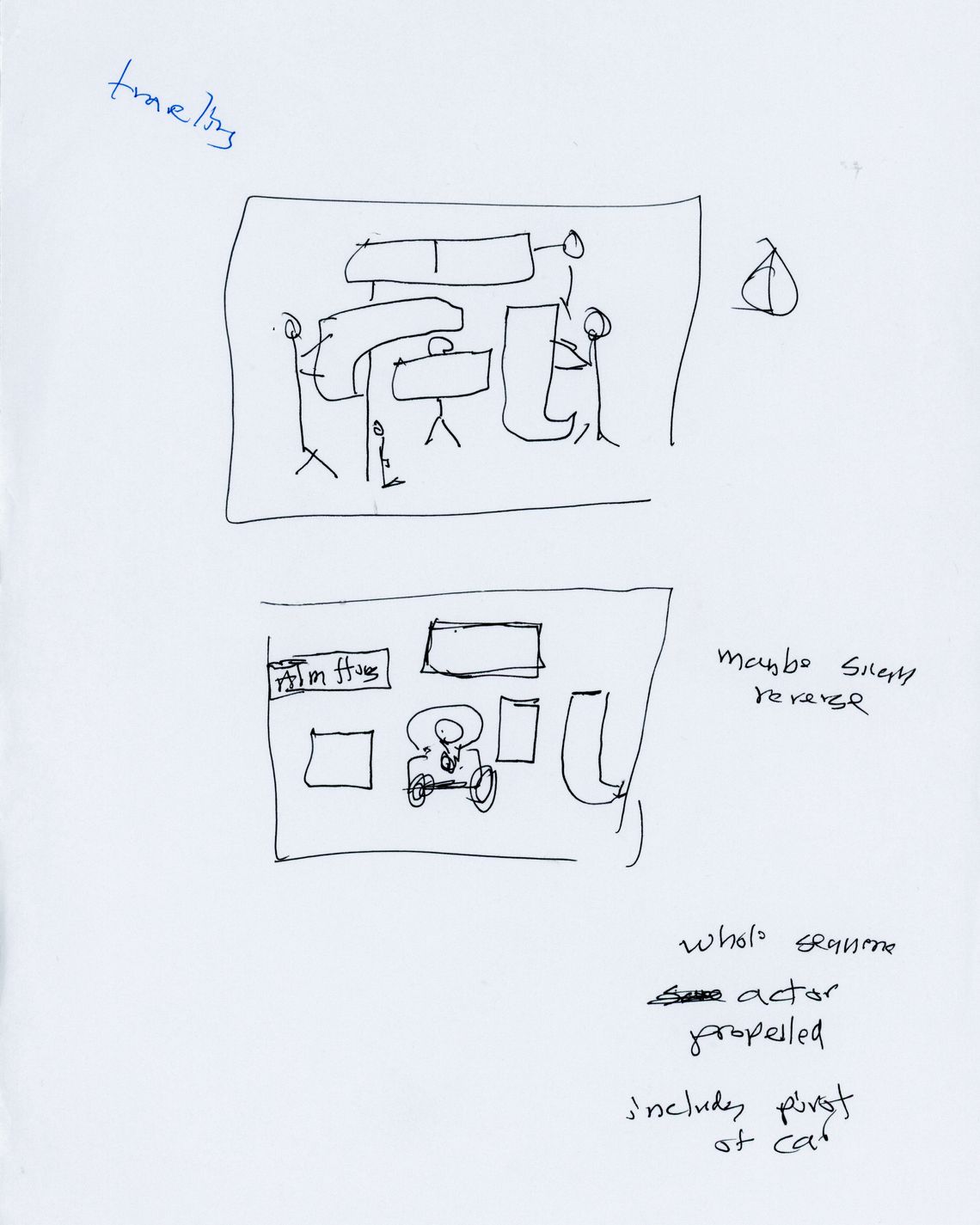

After Rose’s first big anthem, “Some People,” children carrying road signage begin a dance montage, indicating movement across the country.

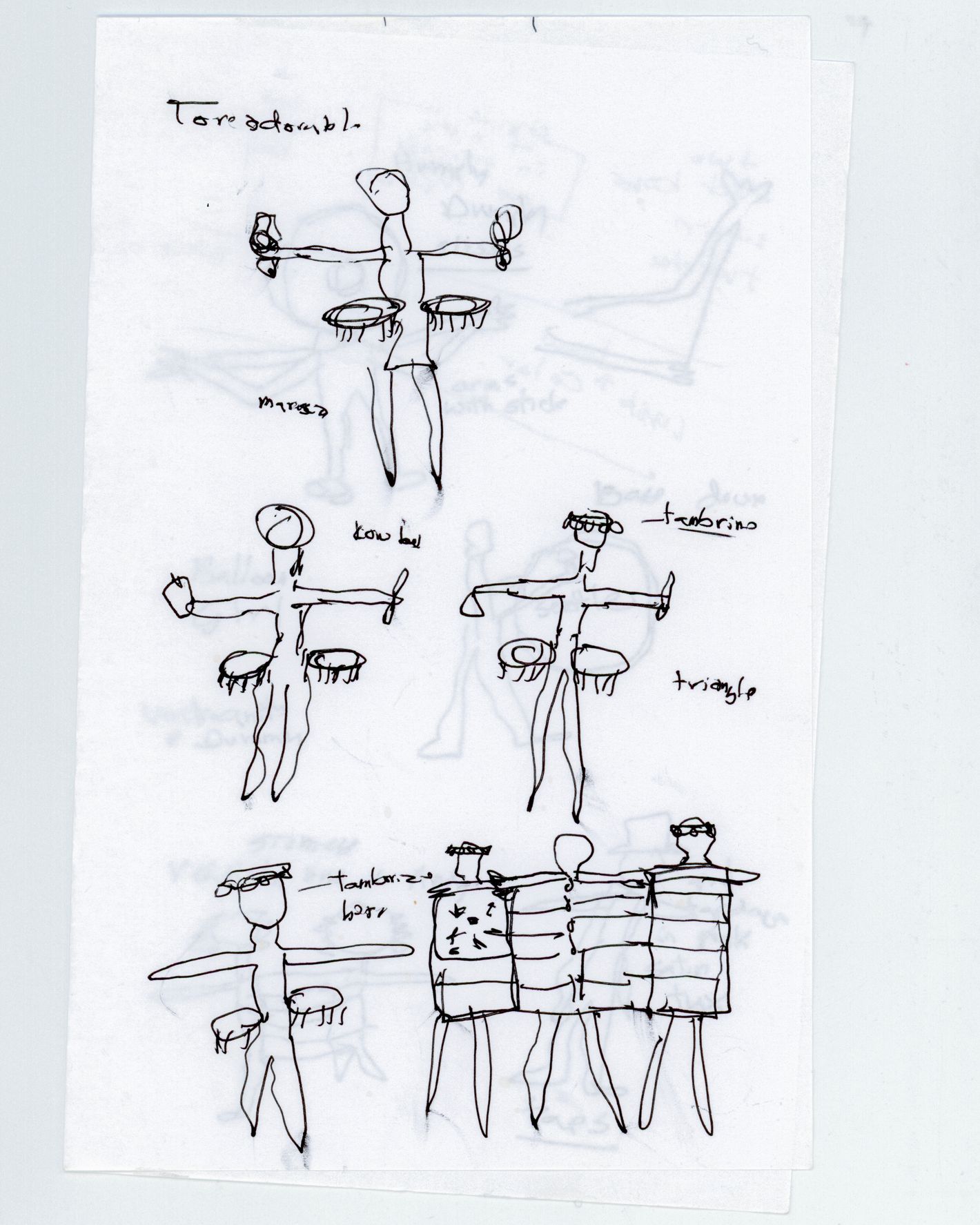

For the children’s costumes, “I just came up with this idea that they would have bongos on their side, and that they had no talent.” Wolfe said. “They had no talent but they had rhythm.”

“The first day we didn’t sing a thing,” he’d said to me. “We read every single word, including the lyrics, so we could start to think about the material in a new way. I was like, ‘Let’s read it and deal with it as literature.’”

I’d noticed that in the first rehearsal I’d seen, McDonald frequently employed a stammer, perhaps to set up the stammer in her final number. Over the course of the process, she still stammered but toned it down, a calibration that finally became exactly right.

This was from an article in the Times from John McWhorter, a Black columnist, arguing that the show ought to be color-blind. Wolfe brought it up with me. “There was that silly op-ed piece about it,” he said. “What he projected onto the casting breakdown, that’s not where my brain was. I didn’t want it to be a backstage musical. I wanted it to be an American musical. And not isolating Blackness — people try to do that, but that’s not how it works. I’ve moved in and out of all the worlds, so I wasn’t just interested in a compartmentalized work.”

There is a final gesture Rose makes to Louise, when she puts her head poignantly on Louise’s shoulder. Joy Woods told me it was Audra McDonald’s spontaneous decision on the night of the first preview, and it stayed in the show.

“This thing blew a hole in the back of my head,” Wolfe said. “I view it as her saying, I can’t do it. I can’t feed them.”

In my last conversation with Wolfe, he was aching from the night before. The feline Wolfe had fallen off the stage. “It’s all these signals your body is giving to you. It’s almost over. Shut the hell up. Just breathe.” So, perhaps first lesson: Directing is very hard work (even if it looked kind of fun).