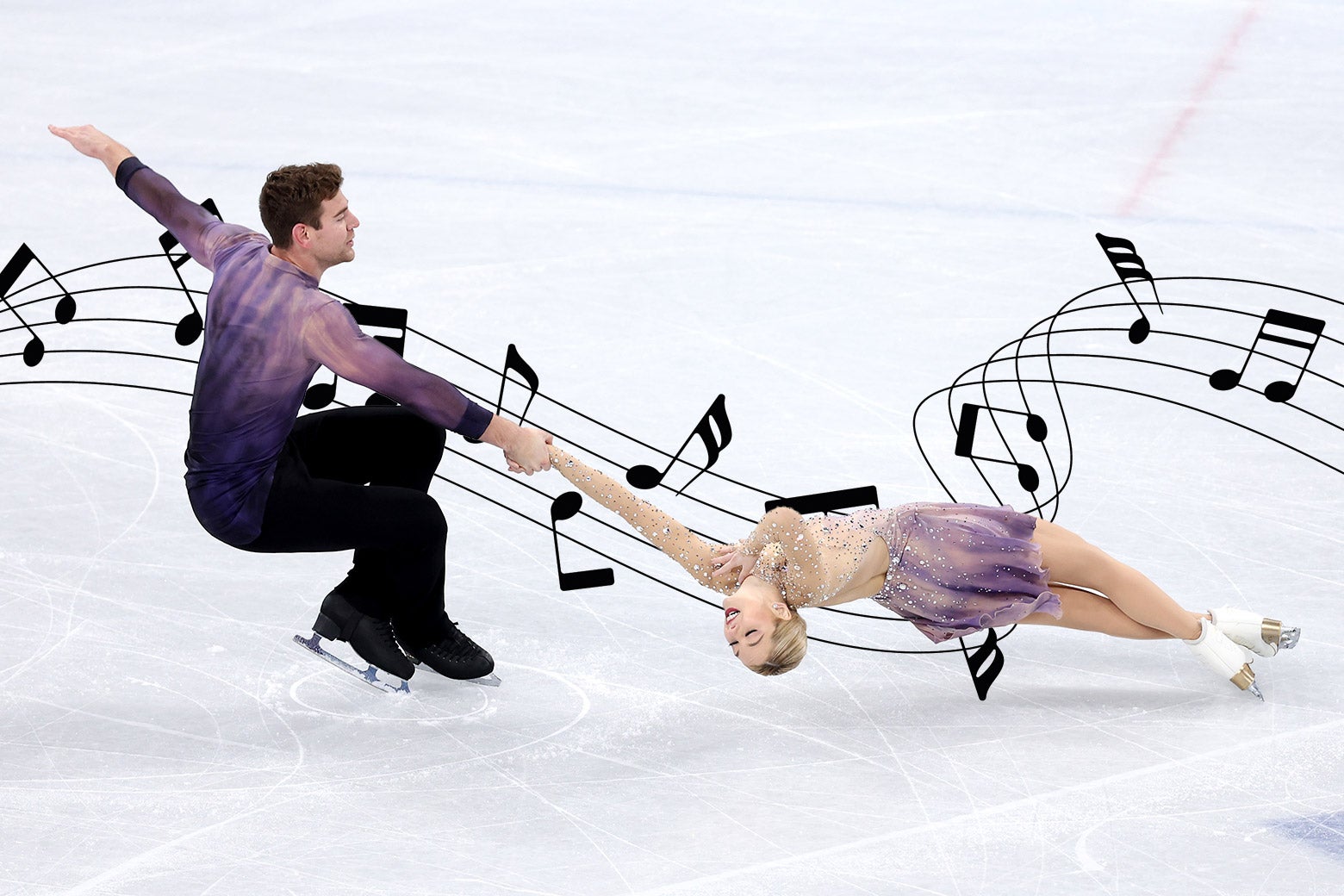

When U.S. champion pairs skaters Alexa Knierim and Brandon Frazier walked into the arena at the 2022 Beijing Olympic Games, ready to compete, they had no idea anything was wrong. “You should know there’s a lawsuit,” Frazier remembers their coach, Todd Sand, telling them. A lifetime of training and sacrifice had led to the few minutes that lay ahead of them, and as they warmed up, perfected makeup, and tried to calm their nerves, it seemed inconsequential. OK, Knierim remembers thinking, Can we talk about this later?

That would not have been her reaction had she known what was coming.

What followed was a lawsuit that has reverberated throughout the sporting world. Athletes, coaches, and choreographers are now facing the fact that they’ve been unintentionally breaking the law nearly every day, through the music that soundtracks their performances. And as rumors of the dollar amounts in musicians’ complaints spread, many athletes began to question if this will be the death knell to artistic sport.

That day in Beijing, Knierim and Frazier were told the worst that could happen is their music would be muted in playbacks of their performance broadcast on NBC’s streaming platform, Peacock. Confident they’d followed the same protocol they had for years—simply submitting their routine’s music to their federation and competition organizers—they didn’t understand what the fuss was all about. The issue arose after Knierim and Frazier competed in the Olympic team event a little over a week earlier. Broadcasts and social media clips of the performance included their song choice, the band Heavy Young Heathens’ cover of “House of the Rising Sun,” and the music tracking software TuneSat had flagged it to the song’s copyright holders. The athletes were personally named, along with U.S. Figure Skating and NBCUniversal Media, in a lawsuit filed by the band’s lawyer (and father), who has filed many similar complaints. The suit accused the skaters of copyright violation and stated that the use of the group’s music “insults the integrity” of the band’s “professional reputation.”

Figure skating exists at a murky intersection of extreme athleticism and artistry, and as artists, Knierim and Frazier told me they would never want another artist to feel like they’ve been ripped off.

Standing in the Olympic arena, Sand offered the unthinkable—playing last year’s music while skating this year’s choreography. But after an entire season of perfecting each—very dangerous—feat to the exact highlights of this song, the duo decided that it was too risky to make that last-minute change for the most important competition of their careers. As it turned out, NBC never did mute their music. And a few weeks later, with no updated advice, they made the same choice at the World Championships, where they took gold.

If you’ve wondered why you can watch other sports streaming long after they took place, but in recent years can’t catch up on “artistic” sports—figure skating, gymnastics, artistic (formerly synchronized) swimming, cheer, ballroom dance, competitive dance—beyond a day or so, this is why. Unlike contact sports, those played on a field, track, or court, these sports rely on music to string together required elements and engage audiences—and music copyright is a minefield. Nearly everyone I spoke to, from music-rights lawyers to entry-level coaches, used the words gray area at least once. While not officially his area of expertise, William Tran, a figure skating judge and television production lawyer, has found himself being asked by panicked skaters and skating officials alike how it all works. Is it only elite athletes who should worry? Can local clubs still use music in their annual children’s shows? Is it a bad idea for athletes to post their performances to social media? How does an individual even get access to music rights?

Tran told me just how complicated it all is: Each song can potentially have dozens of rights holders, which include the artists, the writers, and the label. Each one of these must sign off on the use of a song. To make it more confusing, there are different layers of rights depending on how you plan to use the music.

In order to use a song in any public environment—whether at a sporting event or a coffee shop—you need to pay a performing rights organization such as BMI or ASCAP. Want to cut a song with several others to make the medleys fans are used to, and create choreography that fits to each moment within the mix? You need synchronization rights, too. And while asking a local indie band working out of their garage if you can dance to their music may not seem too hard, try reaching Beyoncé or Taylor Swift.

A quick fix, some have suggested, would be for athletes to just use classical music, which, when not fully in the public domain, often has fewer—likely less litigious—rights holders. Romain Haguenauer, coach to the 2018 and 2022 world and Olympic ice dance champions, said that if figure skating had to stop using popular music, it would be “catastrophic.”

“I think modern music is good for the audience, and especially for younger fans who can relate more to Beyoncé than [the opera] Carmen,” Haguenauer said. “If that would have to change, it’s like we will go back to the past. And that’s never good for sport.”

One potential solution comes from the music licensing company ClicknClear, founded by Chantal Epp, a former World Champion cheer athlete with an extensive background in music licensing.

The company offers prenegotiated global licenses, but not one of the 10 songs I searched for—each commonly used by figure skaters—was available in every country. When you’re an international athlete competing on different continents throughout the season, this makes choosing music incredibly complicated. And it’s been a long process for ClicknClear to garner the incomplete deals they do have. “There are literally hundreds of thousands of record labels and publishers all around the world that we need to have deals in place with,” she told me. “It’s a massive jigsaw puzzle.”

In general, artists are vocal in their praise of athletes who use their music (Elton John was so chuffed to see Nathan Chen win Olympic gold to “Rocket Man” that he featured him in his next music video). But not every artist feels this way, and every time an athlete fails to obtain permission, they’re flouting copyright laws.

To add to the headache, each of these rights can cost thousands of dollars.

“I think most people don’t understand that figure skaters, we don’t make money performing,” Frazier said. Except for small amounts of prize money for the elite few who rise to the top, unlike sports such as the NFL, there’s no signing bonus that offsets the years of investment. Adding music-rights costs to training and travel expenses is, for many, just not feasible.

Because of how integral contemporary music is to many of these events, it was only a matter of time before sport became the focus of copyright infringement cases. In 2014, several cheer music creators were sued by Sony for editing and selling mixes to cheer teams. Cheer pivoted, and today, only “cleared” music can be used, severely limiting what can be played. And this past summer, just a couple of months before the Paris Olympics, artistic swimming teams were told to upload all music to ClicknClear and have it cleared for use at the Games.

ClicknClear helped to rush obtaining music-rights permission—around 22 songs and five routines for Canada’s teams alone—but much of their music only received clearance a week or so before the competition in Paris began, and some teams from other nations who couldn’t get their music cleared did have to change it right before the Games.

Tran and others I spoke to say that even with these added protections, athletes could remain at risk. The real solution will be for Congress to pass an amendment to exempt amateur sports (which accounts for all Olympic sports, among others) from U.S copyright law. And this would still only cover athletes competing in the U.S., albeit one of the most litigious countries when it comes to music copyright violations. But that could take years, and for now, many are left without a clear path forward for sports enjoyed by millions at all levels of accomplishment.

Back on the ice, the advice from the International Skating Union and U.S. Figure Skating has been shaky so far. “Right now, everybody is able to still submit all their music, with the ISU asking, Please, please, start to get the legal clearance,” said Shawn Rettstatt, chair of the ISU ice dance technical committee. “Where that goes further down the road? I’m not quite sure.”

“[Music] was just something that as athletes we took for granted, because it’s never been brought to our attention before,” Knierim said. But with this high-profile lawsuit, no one can continue to claim ignorance.

The lawsuit eventually settled for an undisclosed sum suggested to be in the millions. After skating one more season together, Knierim and Frazier retired from competitive sport, and today, they are pragmatic about the ordeal. But both skaters expressed sadness over the whole situation. “It just honestly puts a bittersweet connection to that Olympic performance,” Knierim said. “It puts this cloud over it, when I think it was a really fabulous program. The music was so wonderful.”