The line between a normal, functioning society and catastrophic decivilization can be crossed with a single act of mayhem. This is why, for those who have studied violence closely, the brazen murder of a CEO in Midtown Manhattan—and, more important, the brazenness of the cheering reaction to his execution—amounts to a blinking-and-blaring warning signal for a society that has become already too inured to bloodshed and the conditions that exacerbate it.

In recent days, journalists and other observers have worked to uncover the motivations of the accused killer. This is a worthy exercise when trying to understand a single, shocking event. But when attempting to understand how brutality spreads across society, studying individual ideologies only gets you so far. As violence worsens, it tends to draw in—and threaten—people of all ideologies. So if in the early stages of a violent upswing, law enforcement can see clearly that the greater threat comes from right-wing extremists, which has been the case in the U.S. in recent years, as the prevalence of violence snowballs, the politics of those who resort to it get messier. That’s in part because periods of heightened violence tend to coincide with social and political reordering generally—moments when party or group identities are in flux, as they are in America right now. As I’ve written for this magazine, eruptions of violence are not necessarily associated with a clear or consistent ideology and often borrow from several—a phenomenon that law enforcement calls “salad-bar extremism.”

We already understand many of the conditions that make a society vulnerable to violence. And we know that those conditions are present today, just as they were in the Gilded Age: highly visible wealth disparity, declining trust in democratic institutions, a heightened sense of victimhood, intense partisan estrangement based on identity, rapid demographic change, flourishing conspiracy theories, violent and dehumanizing rhetoric against the “other,” a sharply divided electorate, and a belief among those who flirt with violence that they can get away with it. These conditions run counter to spurts of civilizing, in which people’s worldviews generally become more neutral, more empirical, and less fearful or emotional.

One way to understand which direction a society is going—toward or away from chaos—is to study its emotional undercurrents, and its attitude toward violence broadly. Medieval Europe, for example, was famously brutish. As the German sociologist Norbert Elias wrote in his 1939 book, The Civilizing Process, impulse control was practically nonexistent and violence was everywhere. But as communities began to reward individuals for proper etiquette, adherence to which was required for entry into the most desirable strata of society, new incentives for self-restraint created substantially more peaceful conditions.

The push toward cooperative nonviolence happened organically, whereby people’s “more animalistic human activities,” as Elias put it, took a back seat to the premium they placed on their communal social life. This change in priorities required and perpetuated steady self-control among individuals across society. “It is simple enough: plans and actions, the emotional and rational impulses of individual people, constantly interweave in a friendly or hostile way,” Elias wrote. “This basic tissue resulting from many single plans and actions of men can give rise to changes and patterns that no individual person has planned or created.” And “it is this order of interweaving human impulses and strivings, this social order, which determines the course of historical change.” Often, when people choose violence, it is because they believe that it is the only path, a last resort in a time of desperation—and they believe that they’ll get away with it.

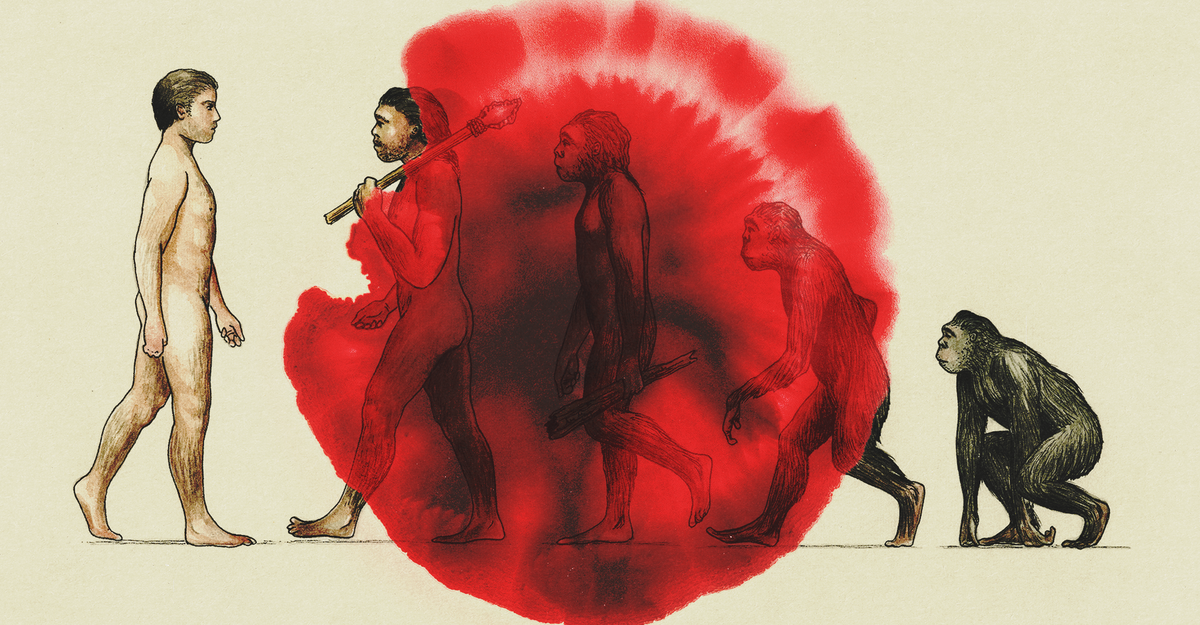

Over the centuries, humanity has become more civilized, largely drifting away from violent conflict resolution. And to be clear, I mean “civilized” in the spirit of Elias’s definition—the process by which the use of violence shifted to the state, and “decivilization” to suggest a condition in which it shifts back to individuals. Today, most Americans enjoy extraordinarily peaceful conditions in their daily life. But obviously violence has never entirely receded, and progress has been uneven; Elias’s interest in violence stemmed from his experience fleeing Nazi Germany. And it’s a fantasy to believe that an advanced democracy like ours is somehow protected by its very nature against extremism. Democracy can be self-perpetuating, but it is also extremely fragile. Complex societies, and in particular backsliding democratic nations, are often among the most violent in the world. (As the writer Rachel Kleinfeld noted in her book A Savage Order, Mexico saw more violent deaths from 2007 to 2014 than the combined civilian death toll in Iraq and Afghanistan over that same period.)

Recent bloodshed is not new to America, not even close, yet this is still a distinctly precarious time. Along with layers upon layers of social conditions that make us especially prone to political violence, the Machiavellianism of contemporary politics has stoked both the nihilism of those who believe that violence is the only answer and the whitewashing of recent violent history. This is how a society reaches the point at which people publicly celebrate the death of a stranger murdered in the street. And it is how the January 6 insurrectionists who ransacked the U.S. Capitol came to be defended by lawmakers as political prisoners. It matters when people downplay and justify violence, whatever form that downplaying and justifying takes—whether by revising history to say something that was violent wasn’t so bad, or by justifying a murder because of the moral failures of the victim’s profession. When growing tolerance for bloodshed metastasizes into total indifference for—and even a clamoring in support of—the death of one’s political enemies, civil society is badly troubled indeed.

My colleague Graeme Wood, who has spent much of his career studying the people and societies that resort to violence, has made the case for a greater degree of sanguinity about political violence in America, given how much worse off many other countries are. In Latin America, Wood wrote earlier this year, “the violence reaches levels where even a successful assassination is barely news.” The thing is, you can’t fully understand the extent to which a society has become inured to violence by counting individual attacks or grotesque social-media posts. You have to assess the whole culture, and its direction over time. A society’s propensity for violence may be ticking up and up and up, even as life continues to feel normal to most people. A drumbeat of attacks, by different groups or individuals with different motivations, may register as different kinds of problems. But take the broad view and you find they point at the same diagnosis: Our social bonds are disintegrating.

Another word for this unraveling is decivilization. The further a society goes down this path, the fewer behavioral options people identify as possible reactions to grievances. When every disagreement becomes zero-sum and no one is willing to compromise, violence becomes more attractive to people. And when violence becomes widespread, the state may escalate its own use of violence—including egregious attacks on civil liberties.

The barrier that separates a functioning society from all-out chaos is always more fragile than we’d like to admit. It can take very little for peace to dissolve, for a mob to swarm, for a man to kill his brother. In a society that is consecrated to freedom, as ours is, the power of the people is not only a first principle but a promise to one another, and most of all a safeguard against the centralized power and violence of the state wielded against the people.

In the weeks after a sharply divided election, ahead of the return to power of a president who has repeatedly promised to unleash a wave of state violence and targeted retribution against his enemies, Americans have a choice to make about the kind of society we are building together. After all, civilization is, at its core, a question of how people choose to bond with one another, and what behaviors we deem permissible among ourselves.

You cannot fix a violent society simply by eliminating the factors that made it deteriorate. In other societies that have fallen apart, violence acts as a catalyst, exacerbating all of the conditions that led to it in the first place. The process of decivilization may begin with profound distrust in institutions and government leaders, but that distrust gets far worse in a society where people brutalize one another. There is no shortcut back to a robust democracy. But one way to protect against the worst is to force change only through processes that do not lead to bloodshed, and to unequivocally reject anyone—whether that person is sitting in the White House or standing in the street—who would choose or justify violence against the people.