Today, Wilbur and Orville Wright are as synonymous with the first to achieve powered flight as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are with the first to walk on the moon. But it wasn’t always so.

In a four-part series dubbed “The Real Fathers of Flight” that ran monthly from January to April 1929, Popular Science writer and editor, John R. McMahon, made a passionate case for why the Wright brothers deserved to be acknowledged as the first to achieve powered flight. His unique account included exclusive interviews with Orville Wright (Wilbur died in 1912) as well as access to Orville’s personal diaries and other documents that chronicled the timeline of their invention, which culminated in the world’s first powered flight on December 17, 1903 at Kitty Hawk, NC.

From the time of that seminal flight until 1942, the Wright brothers were not given credit for being the first to power into the third dimension. Around the world, a long list of aviation pioneers, or their advocates, attempted to claim the honors. Gustave Whitehead, for instance, an immigrant from Germany who moved to Connecticut in the late 19th century, claimed to have achieved powered flight as early as 1901 and again in 1902. For the last century, Whitehead supporters (or Wright brothers critics) have tried to resurrect his claim, but there has never been corroborating evidence; rather, there’s a relatively strong case that his claim was a fantastical fabrication.

Perhaps the most bitter challenge to the Wright brothers’ crown came from the Smithsonian, which bestowed first-powered-flight honors on one of its own—former Smithsonian secretary Samuel Langley. In his 1929 series, McMahon did not hold back criticism of the Smithsonian’s decision: “I believe Government scientists are as human as anybody and those of the Smithsonian were very human in seeking to bask in the fancied glory of a colleague, the ill-fated Langley whose machine crashed in the Potomac River a few days before the historic feat of the Wrights at Kitty Hawk.”

Langley’s Aerodrome did, in fact, take off from the deck of a house boat days before the Wright brothers’ flight, piloted by Langley’s assistant, Charles Manley. But it promptly crashed, and Manley had to be rescued from the river. Langley never attempted to rebuild his Aerodrome, but roughly a decade later it was refurbished by others with ulterior motives to prove that Langley’s design had preceded the Wright’s: the Smithsonian’s new secretary, Charles Walcott, who sought to honor his colleague; and Glenn H. Curtiss, another aviation pioneer, who had been found liable for infringing on the Wright’s patent. Curtiss’s refurbished version did achieve flight, however, it included crucial modifications to Langley’s original design, which the Smithsonian finally acknowledged in a detailed 1942 report. The report also acknowledged the harm done by the Smithsonian to the Wright brothers for propping up Langley’s Aerodrome as the first to achieve powered flight.

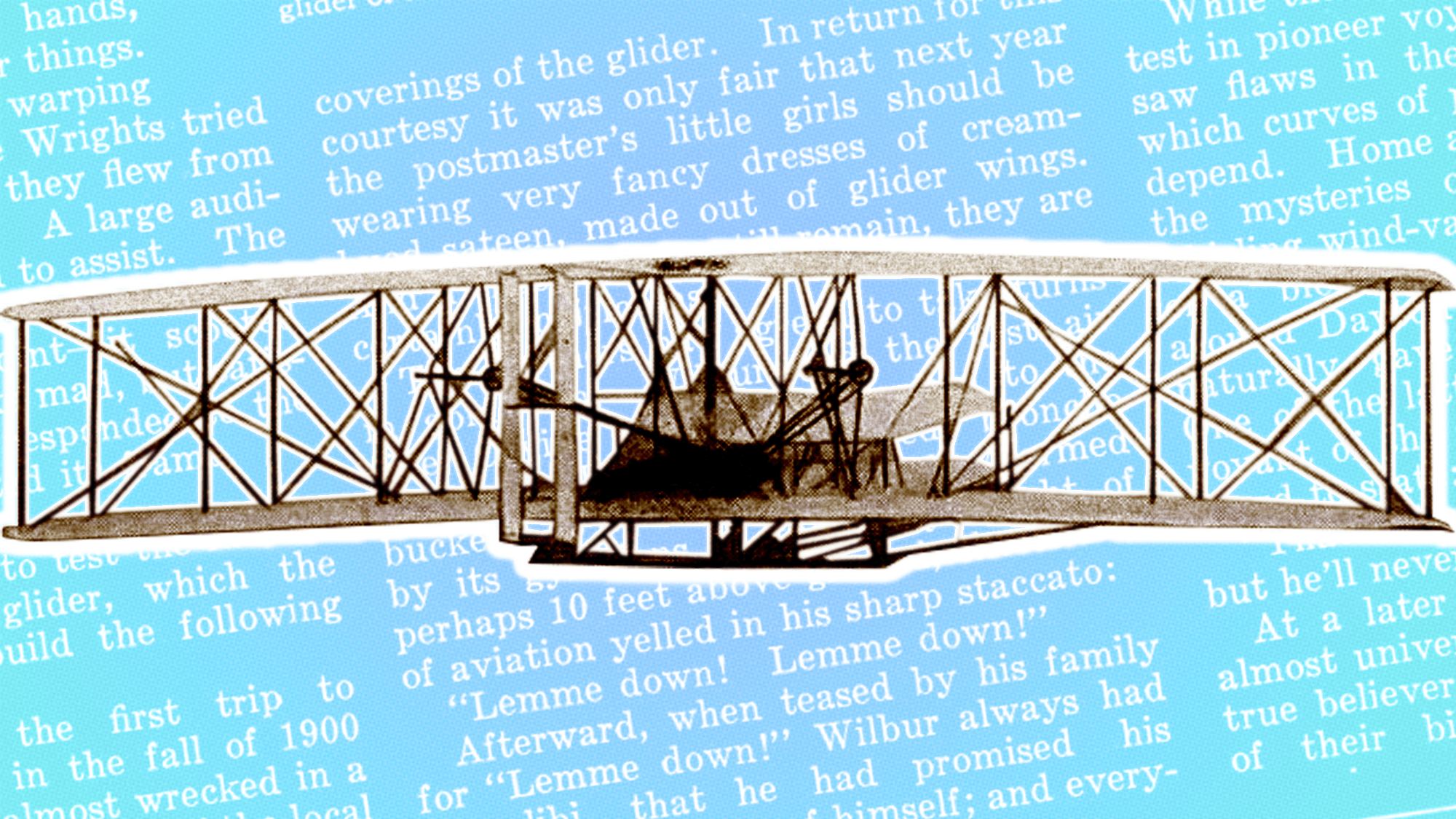

What distinguished the Wright brothers’ achievement from all the others who came before them was the combination of those key ingredients that come naturally to birds: lift, balance, control, and propulsion. Success required a flying machine that could not only leave the ground (lift) under its own power with a human aboard (propulsion), but one that could also remain aloft without flipping over (balance), and be steered by the pilot while in the air (control).

In another Popular Science story written four years before his series, McMahon described the Wright brothers’ novel contributions to sustained flight—chief among them their wing-warping system, which enabled them to slightly twist and bend the wing tips for balance and control.

Describing an 1899 scene in the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop in Dayton, OH, McMahon wrote: “Wilbur held the empty box by its ends while the customer examined its contents. Wilbur’s hands were inclined to be nervously active. He looked down and suddenly realized what he was doing with an empty box—twisting it—warping it. What was this? Can’t hinge wings? Never. But you can warp them! It was simply a great inspiration, like Newton’s falling apple.”

After spending two decades in exile at the Science Museum in London, UK, the Wright brothers’ original aircraft has been on display at the Smithsonian since 1948. As Smithsonian secretary Charles Abbott wrote in his 1942 report, “If the publication of this paper should clear the way for Dr. Wright to bring back to America the Kitty Hawk machine to which all the world awards first place, it will be a source of profound and enduring gratification to his countrymen everywhere.” It’s a statement that, no doubt, made Popular Science proud.

You can read browse more vintage Popular Science issues available for free on Google Books. Download the Popular Science app for free on Apple or Android to get the latest news and analysis on breakthroughs in science and technology.