[ad_1]

In Slate’s annual Movie Club, film critic Dana Stevens emails with fellow critics—for 2024, Bilge Ebiri, K. Austin Collins, Alison Willmore, and Odie Henderson—about the year in cinema. Read the first entry here.

Hello again, dear friends,

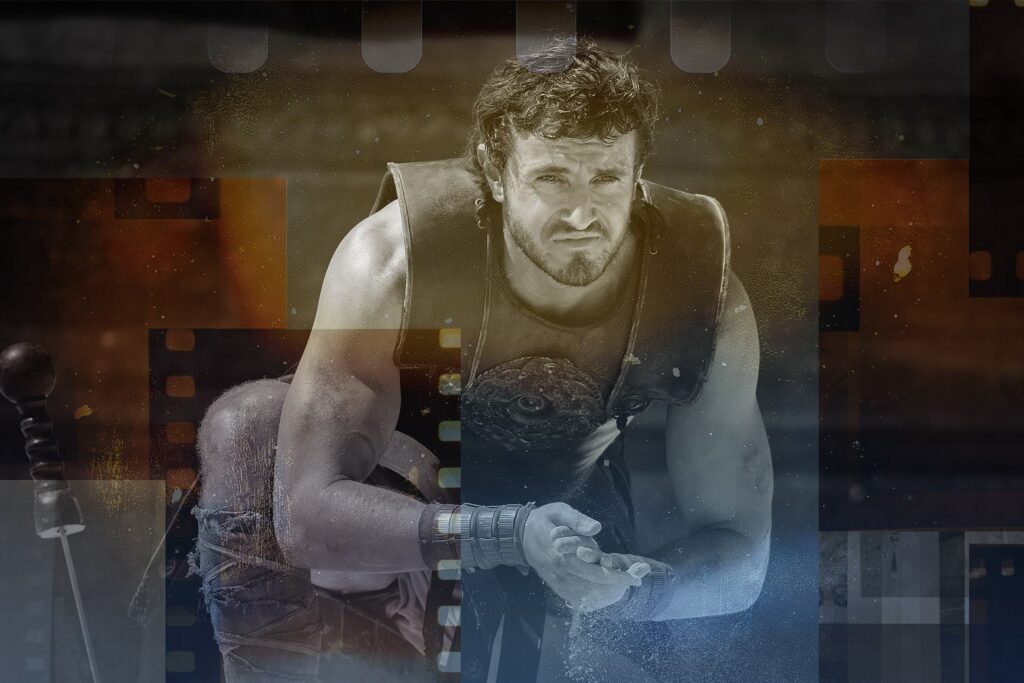

Dana, you asked about endings, which immediately made me think about a funny back-and-forth my Vulture colleagues and I had a few weeks ago about the ending of Gladiator II. None of us could remember how the new movie ended, which was particularly hilarious because we’d all just seen the damn thing; this was a few days after it had screened for critics. We were trying to remember it because the finale of the original Gladiator had been so memorable and moving: “He was a soldier of Rome. Honor him.” That line still sends chills up my spine, 24 years later—and yes, I know that’s not the actual ending, because there’s also that wonderful scene with Djimon Hounsou burying the little figurines in the Colosseum: “Now we are free. I will see you again—but not yet. Not yet!” So, Gladiator has two great endings, while the new one’s got zero. And in the era of nonstop sequelization and splitting-into-two-parts-ification, it seems that we’re in grave danger of forgetting how to end movies well. One of the reasons I prefer cinema to TV is because of all the great endings that cinema has given me over the course of my life; it’s one of my favorite things about the art form. And one of the reasons studio executives and media CEOs probably hate the art form is because movies tend not to go on and on and on and on, unlike TV shows.

If I had to talk about the truly great endings of the year, I’d probably have to talk about Close Your Eyes and Nickel Boys and Anora and Green Border again, and I/we have already talked about those titles. But more than any endings per se, what struck me this year was how many films seemed to change shape by the time they got to the close. Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light begins as a drifting, documentary-inflected drama about three women who work at a Mumbai hospital. But in its final act, it turns into something marvelously unclassifiable, as the three protagonists travel to a coastal town where their lives suddenly take on a magical realist quality. One of them, a head nurse whose husband left for Germany years ago and from whom she has not heard a word, helps save a man from drowning. Then, she has a tender, intimate conversation with this unnamed man in which he seems to become her husband; the film, which already had a dreamy aesthetic, now adopts a dream logic. But their exchange doesn’t resolve into anything. It’s there for a moment, then it’s gone, whisper-thin and indelible.

Another shapeshifter I loved was Matthew Rankin’s Universal Language (No. 5 on my list of the best films of the year), which is also impossible to describe, as the movie takes place in an alternative-reality Winnipeg where everyone speaks Farsi and where Persian and Canadian culture have weirdly melded (though in thoroughly sui generis fashion—this is not a movie about the challenges of immigration or anything like that). Rankin is a great admirer of Iranian New Wave cinema, and he expertly mimics the style of some of those films, though with a disarming sincerity that never feels ironic or referential. Universal Language is also very funny, with much of its first hour steeped in dry Canadian deadpan humor.

But in its final stretch, it becomes a strange and moving meditation on losing oneself. Rankin himself plays a man named Matthew Rankin, who returns to Winnipeg after many years away. His childhood home is now inhabited by someone else. He tries to track down his mother and discovers that, left without a home and with a fraying memory, she is living with a family that she thinks is her own. She believes that the man who took her in is her son, Matthew Rankin. And this other family has played along, caring for her and accepting her as one of them. When the real Matthew finally confronts his mother … well, remember my earlier post about how we saw a slew of movies this year in which another’s gaze transforms one’s identity? Here’s another example of that—an unforgettable, devastatingly powerful one. I write this post on the day that Universal Language was short-listed for the Best International Feature Film Oscar category. (It’s Canada’s submission, and since it’s entirely in Farsi and French, it qualifies.) I suppose it’ll have its work cut out for it—Emilia Pérez, which I do like, is the presumed front-runner—but if I were a member of AMPAS, it would absolutely have my vote.

Universal Language was one of the smaller titles at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, which was filled with all sorts of heavy hitters, and I thank my lucky stars that I saw and wrote about it, as it could have easily gotten lost, as many other excellent films do at those big glitzy events. (Heads-up, publicists: Screen your movies prefest whenever you can.) At the moment, I’m neck-deep in trying to figure out what to see at the upcoming Sundance Film Festival in January and am reminded that the two best films I saw at this past Sundance were titles that didn’t have any hype or big names attached. Shuchi Talati’s sharply observed, beautifully acted coming-of-age drama Girls Will Be Girls (No. 6 on my best-of list) played in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition, and I’d heard about it only because a couple of friends raved about it at Park City. And Ghostlight (No. 9 on the list) I caught on my final day there because I had two hours to kill and a screening was about to start. I had zero idea what it was or what it was about; I didn’t even know if it was scripted or documentary, although it’s a safe bet to assume I’d gotten some emails about it. (Sorry, publicists: It doesn’t always work out.) Ghostlight rocked my world—and in a weird way, my going in not knowing anything about the film helped, even though it’s not a twisty, surprise-y, or plotty picture. So, I won’t say much about it here, other than to note that on one level it’s about the transformative, terrifying, life-changing power of art. In the first paragraph of my review of Ghostlight, I described the circumstances under which I saw the film, then I told everyone to stop reading the review. I know for a fact that some people did stop reading, went and saw the movie, and loved it, then came back to read the rest of the review. (Or at least that’s what they told me.)

Of course, if I did this for every movie I’d soon be out of a job. And in a world where it’s harder and harder to learn about the existence of films that aren’t just new entries in long-running franchises, critics should probably be writing more, not less.

This is probably a dumb way to end my post, but, well, Ridley Scott will understand.

Bilge

Read all of the entries in Slate’s 2024 Movie Club.

[ad_2]

Source link