One crafty bird species may be the latest example of social learning in nonhuman animals. In an experiment with great tits (Parus major), a team of scientists found that when the birds move to a new environment, they pay very close attention to what the other birds are doing. This ultimately leads them to quickly adopt useful new behaviors. The findings are described in a study published November 14 in the journal PLOS Biology.

Getting to the cream

Several animals that live in groups learn from one another, including elephants, whales, and some primates. However, the great tit is the species that has busted open a window into understanding animal social learning for scientists.

In the 1920s, residents from a small town in England were the first to report that these small birds were opening up foil lids on milk bottles to get to the cream inside. Soon after, people across Europe reported the same behavior with their unsecured milk bottles. Scientists began to speculate that birds across the continent were possibly learning this behavior from one another.

[Related: These birds appear to be signaling ‘after you.’]

Exactly how they were doing this remained a bird secret until 2015. A team led by behavioral ecologist Lucy Aplin conducted an experiment on a population of great tits in an English forest. The experiment showed that the birds were able to learn how to get food out of a puzzle box by copying the solution from others. This confirmed that the original milk-raiding birds were passing on their methods to various flocks.

“Social learning is a great shortcut when it comes to safely testing new waters,” Michael Chimento, an evolutionary biologist and co-author on the new study from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and University of Konstanz, said in a statement. “Paying attention to what others are doing gives you the chance to see whether a new behavior is beneficial, or potentially dangerous. Copying it means that you too can reap the reward.”

Chimento and Alpin were curious if there is a specific incident that triggers social learning in tits, allowing the birds to more efficiently get to their rewards. Some theoretical models suggest that when they move to a new place, they can learn from others.

“But nobody has experimentally shown this in non-human animals,” said Chimento.

Birds on the move

When birds immigrate, they move to a new place with the intention of staying. Migrations are more temporary and seasonal. In the new study, the team developed an automated puzzle box system to test their hypothesis that bird immigration spurred learning. They created experimental social groups of wild-caught great tits. Each group had a “bird tutor” who was trained to access food from a puzzle box by either pushing the door to the right or left. One bird tutor was then released into each group, so that the flock mates could learn to use one solution over another.

The immigration event came next. Birds who pushed the door to the right were transferred into aviaries where the resident birds were pushing the door on the left and vice versa. The new birds saw more than just that the resident birds were opening the puzzle box in a new way. Some groups also observed that the residents were getting a superior reward by using their methods.

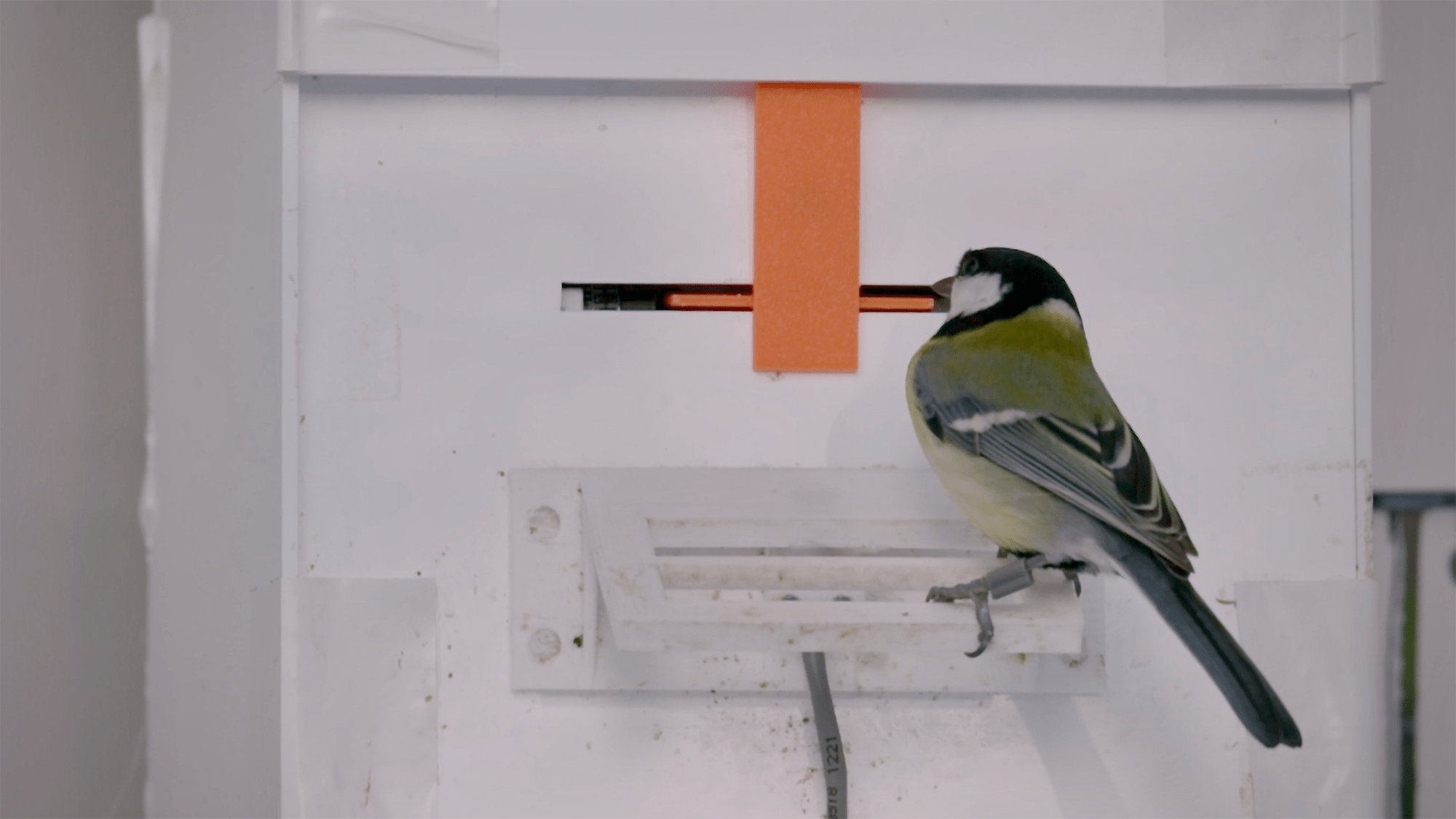

A great tit (Parus major) solving a puzzle. This puzzle is from a separate experiment and the design differs from the puzzle used in a PLOS Biology paper published November 14, 2024. CREDIT: Hervé Glabeck – Docland Yard.

VIDEO: A great tit (Parus major) solving a puzzle. This puzzle is from a separate experiment and the design differs from the puzzle used in a PLOS Biology paper published November 14, 2024. CREDIT: Hervé Glabeck – Docland Yard

“What’s important is that the immigrants were blind to the fact that the food reward had changed,” said Chimento. “Immigrants could only know something changed by either watching the residents use the puzzle, or by trying the other side themselves.”

After being released into a new aviary, about 80 percent of the birds switched their method immediately. Instead of trying the food retrieval that had been trained on, the immigrants used the resident solution on their first try. According to the team, this stark result makes the case that social learning is what’s happening.

“Of course we can’t ask the birds exactly where they were getting their information from, but these behavioral patterns are striking enough to suggest that the birds were watching residents very closely from the moment they entered their new social group,” said Chimento.

Changing foliage

The immigrant birds were not only moved to a place where the residents had better food. Their visual world was also drastically altered when the scientists changed the foliage in the experimental aviaries.

This altered visual environment proved to be the linchpin for learning. In the trials where the foliage was not changed, only 25 percent of the new birds tried the resident solution on the first attempt, even when the locals were getting better food. According to the team, they were not necessarily ignoring the residents, but they look significantly longer to switch over to the more rewarding solution.

[Related: Great tits are killing birds and eating their brains. Climate change may be to blame.]

“Our analyses suggested this was because they weren’t as influenced by the residents,” Chimento said.

While this evidence shows that immigration has an impact on how animals learn from one another in the lab, it can be profound in the real world.

“In nature, animals are often moving from one environment to another, so it’s helpful to have a strategy to weed out what are good and bad behaviors to use in the new place,” Lucy Alpin, a study co-author and behavioral ecologist now at The Australian National University and University of Zürich, said in a statement. “Our study provided the experimental evidence to show that this is also what happens in real life.”