Like most industries, institutions within the culture sector are starting to integrate general-purpose A.I. tools like ChatGPT, text summarizers, and chatbots into everyday operations to boost efficiency. To truly tap into the revolutionary potential of machine learning, however, they will need specialized tools that can be customized for specific tasks.

This problem calls for an interdisciplinary approach that would allow experts at cultural institutions to collaborate with A.I. developers. The resulting models should be easy enough for museum staffers to use so that they can be used internally by institutions of all sizes.

This mission was forefront of a recent three-year research project Transforming Collections: Reimagining Art, Nation, and Heritage in the U.K. It sought to determine how machine learning could usefully address longstanding issues facing the custodians of our public collections, such as how to counter structural biases or how to surface suppressed histories. The project is part of the five-year Towards a National Collection program, which aims to find technological solutions to remove barriers between cultural institutions in the U.K.

Stephanie Dinkins speaks at the Museum x Machine x Me conference at Tate Modern in London in October 2024. Photo: Josh Croll, courtesy of Tate.

Findings from Transforming Collections were made public at the Museum x Machine x Me conference at Tate Modern in London in early October. Artnet News sat down with Professor Mick Grierson, research lead at University of Arts London’s Creative Computing Institute and co-investigator of the project, to hear his three main takeaways.

1. The Power of Interdisciplinary Computing

Machine learning solutions for the culture sector must be developed by an interdisciplinary team of experts that includes curators, art historians, and data protection officers.

“Our collaborators in museums at Tate and elsewhere were giving us the examples we needed to understand what it was A.I. was actually going to be useful for,” explained Grierson. “Our goal was to build something that allowed them to do that in the way they wanted to do it, and that meant really understanding what their concerns were.”

He offered the example of computer scientists enabling the option for museums to automatically label digitized items from their collections to make the creation of large, searchable databases more efficient. “We discovered within about 30 seconds that this was never going to work,” said Grierson. In one case, for example, they found that general-purpose computer vision models were failing to denote the race of a subject’s photographs or paintings, which is relevant information in the museum context, especially when decolonizing collections is of high priority.

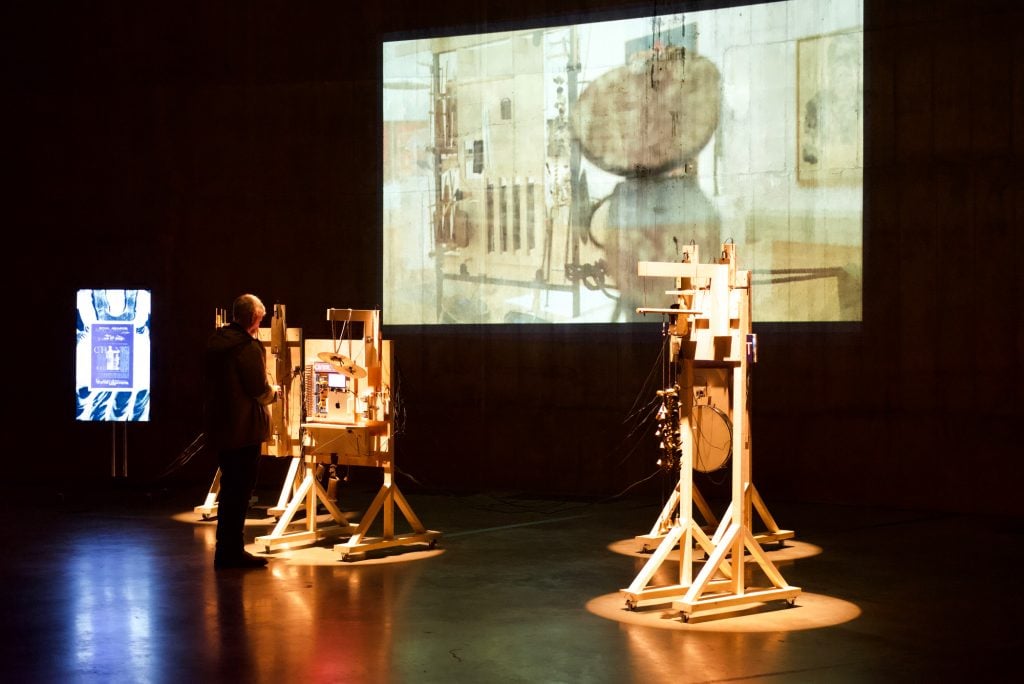

Museum x Machine x Me conference at Tate Modern in London in October 2024. Photo: Josh Croll, courtesy of Tate.

“There’s no commercial incentive [for Big Tech] to manage this issue, so it doesn’t get fixed. What you need is a public sector approach” Grierson added. “What we have to do is change the models by training them [ourselves].” This approach also suits museums that understandably don’t want to freely give away their data to A.I. companies.

2. Addressing Longstanding Issues in the Public Sector

The private sector’s reluctance to solve issues that are of great importance to public institutions creates an opportunity to instead build sector-specific tools that will “break the narrative we are sold by large tech companies.” As Grierson explained, “these are actually quite simple systems that you can retrain for your own purposes and make do what you want to do, through much more than just prompting.”

For example, many museums are currently focused on identifying omissions or absences in their collections. An A.I. tool developed by the Transforming Collections project allows users to analyze and search texts or images around a certain theme and identify even subtle structural biases. This “analyzer” model can be downloaded by museum workers and customized to their own context-specific needs, even using just small amounts of data on a local I.T. system. If useful, the model can then be easily shared with external colleagues.

Erika Tan, Ancestral (r)Evocations (2024). Image courtesy of UAL Decolonising Arts Institute.

Tools like these should counter the notion that A.I. is too complicated to use unless you have expertise in the field. “We can empower people to embed their perspectives in technology,” said Grierson. “This is just a computer doing some stuff. There’s no magic. If there’s an interface that allows you to do it, you can do it.”

3. The Importance of Inclusivity

Ideas shared at A.I. conferences can feel abstract when we can’t see how they might be realized in the real world. A week-long program of cultural events ran alongside the conference, spotlighting artists working with A.I. through presentations installed by students from UAL’s creative computing MSc course.

Together, these projects “really represented the inclusivity we were going for,” Grierson said. He highlighted the contribution of Stephanie Dinkins, a prominent artist interrogating how A.I. intersects with race and gender, whose keynote conversation kicked off the conference.

Another standout was Erika Tan’s Ancestral (r)Evocations, for which she fed data on items in the Southeast Asia collections at the Tate and Wellcome into a “Diagnostic Instrument,” which converted it into an affecting sound installation.

“These artists thought about the [museum] archive in the context of data and information,” said Grierson. “You got a sense of a community engaging with the ideas and the technology in a meaningful way. It didn’t feel like we were just a bunch of academics. It felt alive.”