This article is taken from the November 2024 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

A cute little video pops up on Instagram. What you see is a little boy, maybe three years old, sitting in the conductor’s seat in an Italian opera house and waving a baton as long as himself at a background recording of a Beethoven symphony. “Adorable!” cried Classic FM.

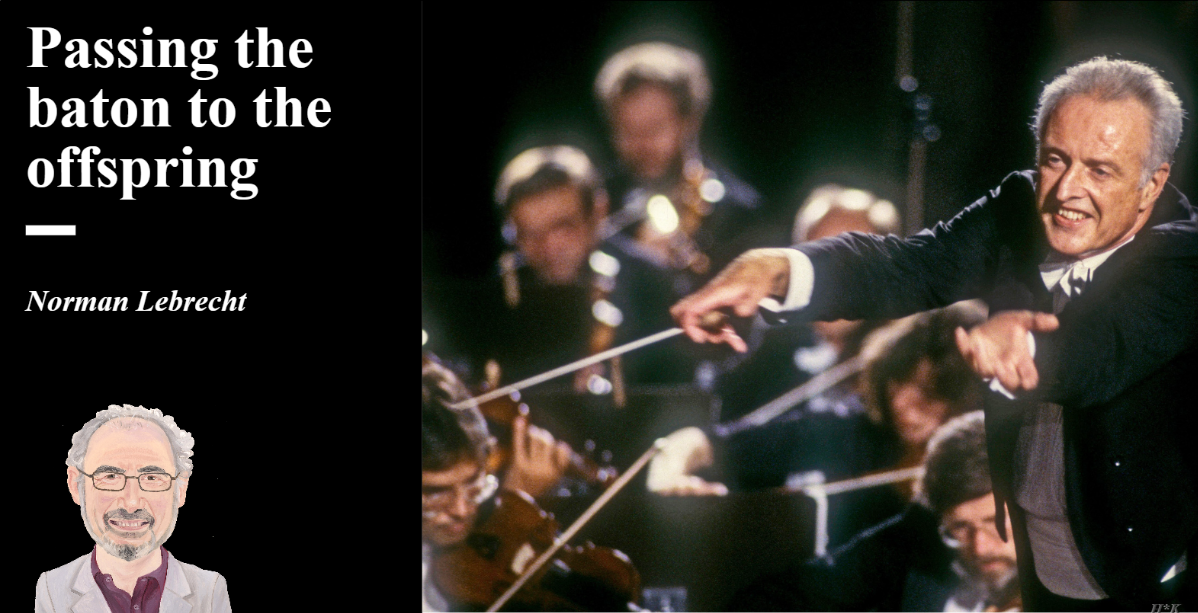

Up to a point. The boy’s father is Francesco Ivan Ciampa, conductor at the Carlo Felice Theatre in Genoa. His intention, we may assume, was to imply that maestro talent runs in the genes. That supposition seems to be growing more widespread.

Barely had I shut the Insta link than news popped up of regime change in Mainz, a town in western Germany. This is personal to me. My grandfather left Mainz in 1885 and, whilst none of us has ever been back, the prospect of a young Generalmusikdirektor was cheering, the more so since his name was familiar.

Venzago, it is, Gabriel Venzago. Familiar because he is the son of Mario Venzago, who used to be the highly capable music director of Indianapolis, Berne and Gothenburg. Is the son as good as the dad? Time will tell.

Venzago is not alone. There is half a football team of son-ofs who are presently skinning up the slippery pole. To name a few of the likelier lads: Taavi Oramo, son of BBC conductor Sakari; Ken-David Masur, chip off the late Kurt; Min Chung, born of Myung-whun; Masato Suzuki, heir to the Bach Collegium Japan. Maxime Tortelier is the son of Yan Pascal. All have agency contracts and good jobs in prospect.

Some go in disguise. François López-Ferrer conducted in Cincinnati, where his father Jesús López-Cobos was formerly in charge. The son of a knighted British baton conducts around the world under an assumed name.

Two Swiss orphans scaled Mont Blanc: Philippe (Armin) Jordan is music director of the Vienna State Opera and Lorenzo (Marcello) Viotti of Netherlands Opera. Both lost their fathers at a formative age.

More prosperous still are Paavo Järvi, firstborn of Neeme; Vladimir (Michail) Jurowski and Mariss (Arvids) Jansons. All three saw their outstanding fathers suppressed under Soviet rule and were incentivised to make their own way. Jurowsky now heads Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Paavo Järvi has the Zurich orchestra.

And there are more. What we are seeing here is not a conspiracy of podium nepotism but a diverse and largely hidden transmission of a musical function by means of informal tuition, ethical example and commercial manipulation. Do I still have your full attention?

Mariss Jansons told me once he spent every spare minute of his boyhood watching Arvids make magic with his Riga musicians. Paavo Järvi saw Neeme spend every cent he earned in Sweden, filling a suitcase with scores unobtainable in Soviet Estonia. The conductor sons of Kurt Sanderling — Thomas, Stefan and Michael — learned survival skills from their father’s close associate, Dmitri Shostakovich.

A conductor’s child is privileged simply by sitting at table. A student advised me he learned most about directing an orchestra from watching Wilhelm Furtwängler of the Berlin Philharmonic wield a knife and fork at a private lunch. Conducting is a nebulous art. Waving a stick implies threats and spells. Conducting is the musical role a charlatan can most easily simulate.

What cannot be faked is the knowledge, skill and character that comes from a life’s immersion in music, along with an uncontainable urge to reshape it. Listening to a rare Soviet recording of Arvids Jansons conducting the Tchaikovsky Pathétique, I can readily imagine Mariss absorbing his father’s experience and envisaging how to remould it. In rehearsal breaks, I would see Mariss move one orchestral chair after another a millimetre to the left or right.

There can be an Oedipal impulse at work. The most famous son-of, Carlos Kleiber, conducted his father Erich’s signature operas — from the ultra-complex Wozzeck to the utterly trivial Die Fledermaus. But no Carlos performance is like Erich’s. Carlos deconstructed what he saw as a child, fostering a scintillating conflict.

Vienna Philharmonic players who worked with Carlos consider him the most fascinating conductor they ever faced. Much of that came from being the son of a maestro whom he had to defeat. Erich had done everything in his power to discourage Carlos from becoming a conductor.

The music industry has reasons for favouring the sons of conductors. In a field where name recognition is rare, a young baton with an established brand name saves a lot of explanation and promotional expense. The agent, anyway, has no choice if a cherished client says, “Please sign up my boy, he’s ever so talented … ”

One London-based agency has a neat little pack of nepo-batons, three or four of them. No daughter has yet been advanced.

Yet, despite rare successes, the idea that musical talent passes from Gen-1 to Gen-Z is fallacious to the point of absurdity. True, there were sons of Johann Sebastian Bach and Johann Strauss who earned a name as composers, and there are families in France called Couperin, Casadesus and Tortelier who keep the business running long past its sell-by. The Bassanos of Venice had an even longer run.

But these are isolated exceptions in a general drift to mediocrity. Mozart’s son was a minor civil servant, as was Beethoven’s nephew. Berlioz’s son died a sailor. The six daughters of Sibelius stayed home and managed the estate.

Genius in music does not strike twice in the same gene pool. Conductors are made, not born to it. The only Furtwängler you’ll see nowadays is Maria, star of a detective series on German television. The sons have set.