Boston non-profit Aurelia Institute has created a pavilion showcasing its self-assembling geodesic dome, designed to allow space professionals and the general public to “lead good lives” in zero gravity.

A continuation of Aurelia Institute co-founder Ariel Ekblaw’s PhD thesis at MIT, TESSERAE (Tesselated Electromagnetic Space Structure for the Exploration of Reconfigurable Adopative Environments) aims to enrich the quality of life for space farers by providing larger living spaces and interior design elements, such as an inflatable couch.

The concept centres around two major elements, a self-assembling, modular structure made from magnetized panels that would drift together in space to form a geodesic dome, and a series of interior design elements, led by co-founder Sana Sharma, that would make living in space more hospitable.

TESSERAE is designed to float in low Earth orbit (LEO), a “cocoon” around the planet with a maximum altitude of 1,200 miles that is currently inhabited by the International Space Station (ISS) and “many proposed future platforms” according to NASA.

“We’re not necessarily trying to help people who are going to Mars,” said Ekblaw. “We are much more interested in increasing the volume that’s available for people to lead good lives in low Earth orbit that are commuting from Earth to space.”

“We really do want to push back a little bit on this idea of space exploration for abandoning Earth,” she continued. “I really love Earth. The goal is to have space in service of Earth.”

Proposed for flight in the 2030s, TESSERAE’s final structure will be composed of electromagnetic hexagonal panels that flat-packed and released from “a glorified Pez dispenser”, according to Ekblaw.

In space, they would self-assemble to form a floating, geodesic dome, informed by American architect and technologist Buckminster Fueller’s well-known creation, which could then go on to attach to others through passageways.

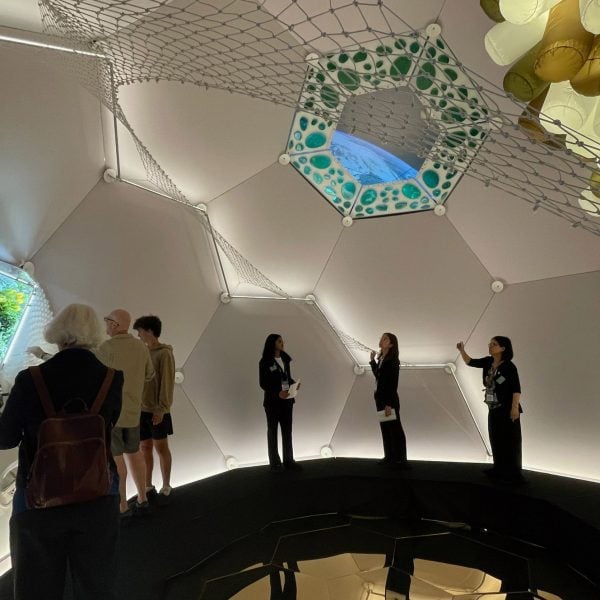

A small-scale version of the technology was flown on the ISS last year, and recently, Aurelia Institute displayed a full-scale 20-foot by 24-foot (6 by 7 metres) mock-up of its approximate shape and size in Boston, with plans to show it at various institutions.

According to the team, the shape creates more open room than found in pre-existing spacecraft, which are currently “constrained” by the size of a rocket.

“One of our goals was really to say, ‘How do we design big space structures that will be floating in orbit that can be much, much bigger than your biggest rocket?'” said Ekblaw.

“Right now, the rocket is a constraint for how big of a thing you can squeeze in there.”

This extra space might act as a communal space for researchers after working abroad on the ISS or as a more comfortable space for the general public visiting space, according to the team.

“One of the things that we’re trying to push back on is the space industry,” said Ekblaw. “If you see images of the inside of the ISS, it looks like a science lab. There are wires everywhere. People look at that and they don’t see themselves in that future.”

“What would it take to design very intentionally a different type of space in space? A different type of habitat that’s way more welcoming and engaging to a broader swath of humanity, [not just] crazy talented astronauts, but open community?” Ekblaw asked.

“Democratizing access to space means we have to design for that.”

For the interior of TESSERAE, the team created a series of fixtures and furniture designed for a zero-gravity lifestyle, including a hand-knotted net for pulling nonself across open space, and an inflatable couch that extends up the length of one side that one can “nestle” into to “stay put.

The pieces were designed based on feedback from over 20 astronauts, cosmonauts and spaceflight participants about “what life in space was like outside the parameters of their mission”.

“The most fascinating thing we learned was the emphasis on collaboration, care and comfort,” said Sharma. “How people in a stressful environment come together and take care of each other in orbit.”

“Right now, because the ISS is a lab, a lot of that’s improvised. So the first dining table on the ISS was built by the astronauts themselves because they wanted a place to come together.”

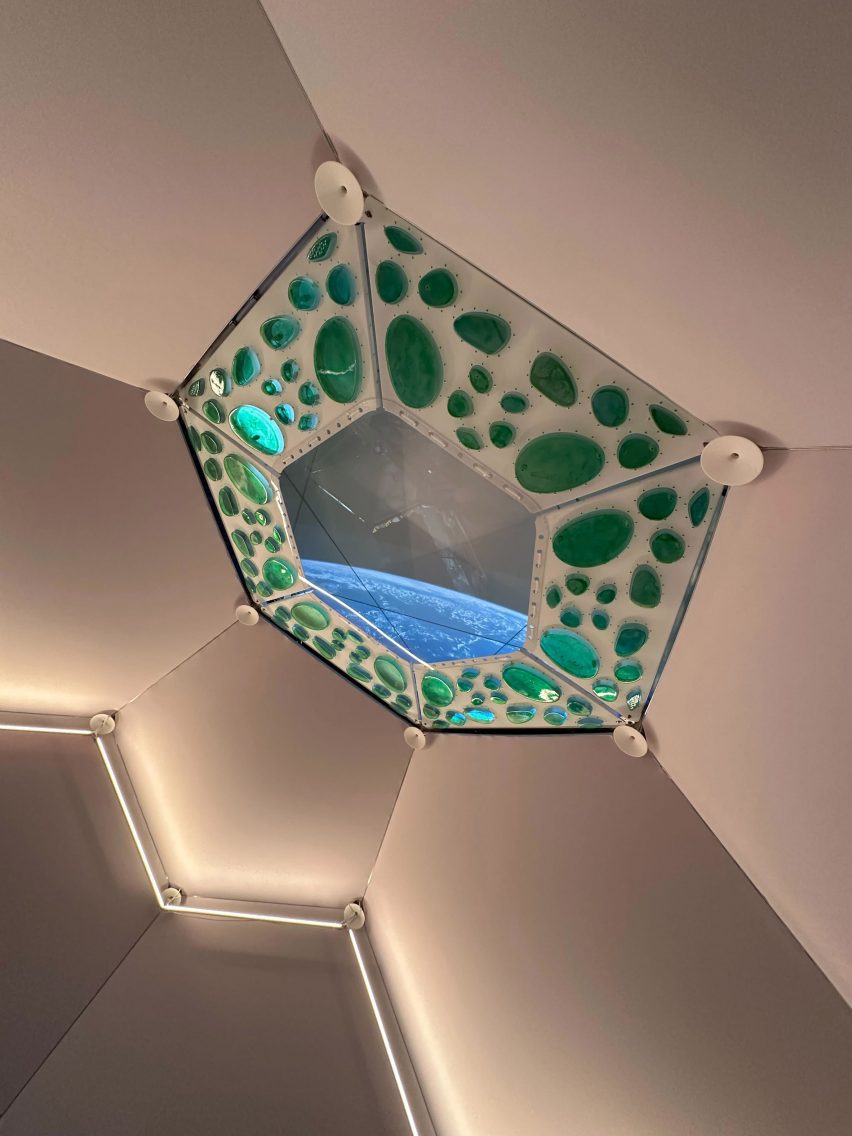

Led by Sharma, the team also worked with plant life, designing a watering system to grow leafy greens and creating algae-filled “stained glass windows” that could encircle a view of space.

“The idea is that the sunlight streams through these algae pools,” said Sharma. “The algae then produces oxygen for the crew to breathe. It’s basically a supplemental life support system.”

Aurelia Institute is working on developing further interior panels and fundraising to display the pavilion elsewhere, with the ultimate goal of working with NASA or another commercial space company.

“We really want to democratize access to space, just to make sure that that economic benefit is shared by a lot of people,” said Ekblaw.

“It’s kind of a combination of pragmatic – let’s make sure there’s equity in the future of space exploration, and then also philosophical – let’s make sure that people have a chance to really appreciate space themselves.”

Other recent projects designed for space include a storage device to be sent to the Moon by BIG and a Lego brick made from space dust created by European Space Agency.

The photography is courtesy the Aurelia Institute unless otherwise stated.